Auction: 21002 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 148

'Dear Mrs Holt

We were flying on a daylight raid on V1 storage depots (i.e. flying bombs stored in a tunnel near Reims) that evening, and just after we had dropped our 12,000lb bomb I felt the plane being badly hit. Told the crew to bale out and Bert being my mid-upper gunner had to climb down, get on his 'chute and bail out of the rear door. It all happened so suddenly that I had just been give my 'chute from the Engineer then he rushed forward to get out of the escape hatch. All of those in the main cabin viz. the Bomb Aimer, Navigator Wireless Op, Engineer and myself go out of the front hatch whereas the Mid-Upper & Rear Gunners go out the back door when there is no time to get to the front. I found the controls had been knocked away by the hits and whilst the others piled into the front the 'plane went into a steep dive & began spinning down. By this time I had my 'chute on and began to get out being unable to do any more at the controls. The control column was holding me down against my chest type 'chute pack. I then tried to open the side window & get out that way but it wouldn't open. Managed then to struggle out of the seat and tried to open the other side window which wouldn't open either.

Still spinning down I couldn't get forward to the escape hatch; I then thought of the dinghy escape hatch above my head and a little behind. Struggled to this & as I turned the handle felt a lot of banging and scuffling. Next thing I knew I was falling through the air pulled the rip chord of my 'chute & it opened.

A chap who was on the same raid that evening from our squadron was up seeing me. He told me how he saw bombs falling from a 'plane above us, on top of us hitting the wing & fuselage. This sort of thing rarely happens but on a small target & with a fairly heavy force made it more likely.

After I was captured on landing the Germans took me to their Headquarters about a mile away. On the way I saw part of my 'plane and asked them to let me look at it. Beside the 'plane they had my two gunners laid out & I looked to identify them. You've no idea what a shock it was to me to find Bert and my rear gunner to be killed. I don't know whether they were hit by the bombs or not, but I was certain I was the only one trapped in the 'plane when it was spinning down. It was only that the nose of the 'plane came off or I'd never have lived myself.

I do hope I haven't been to callous in describing everything as it happened but U thought you'd want to know everything. I'm afraid that only the W/Op and myself are alive out of the crew & he too was thrown clear on the way down. I have no idea what happened to the others. Whether their 'chutes didn't open or not I couldn't say.

I need hardly say what a fine fellow Burt was & I can assure you, you have the greatest sympathy from me and all on the Squadron, in your sad bereavement. He was exceedingly well liked, especially having completed almost two tours of operations. Please give my sympathy to his wife & if there is anything at all I can do for you please let me know & I will do my very best to do it.

Goodbye for now & thank you for Bert, a fine lad & worthy member of my crew.'

Flight Lieutenant 'Bill' Reid, V.C., writes to the mother of Flight Sergeant Holt

A poignant campaign group of three awarded to Flight Sergeant (Air Gunner) A. A. 'Bert' Holt, No. 617 Squadron, Royal Air Force, who was killed in action on Ops on the V-rocket sites at Rilly-La-Montagne on 31 July 1944 whilst a mid-upper Gunner of the legendary Flight Lieutenant 'Bill' Reid V.C.'s Lancaster ME557 KC-S; their Lanc was torn apart by a falling bomb from another aircraft some 6,000ft above, Reid survived and was taken prisoner but the gallant Holt perished

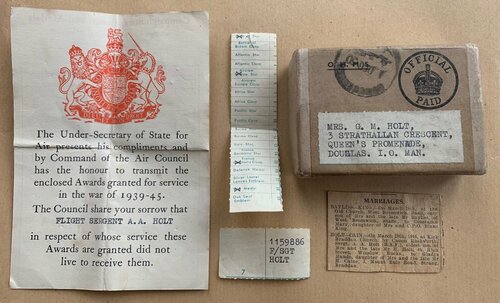

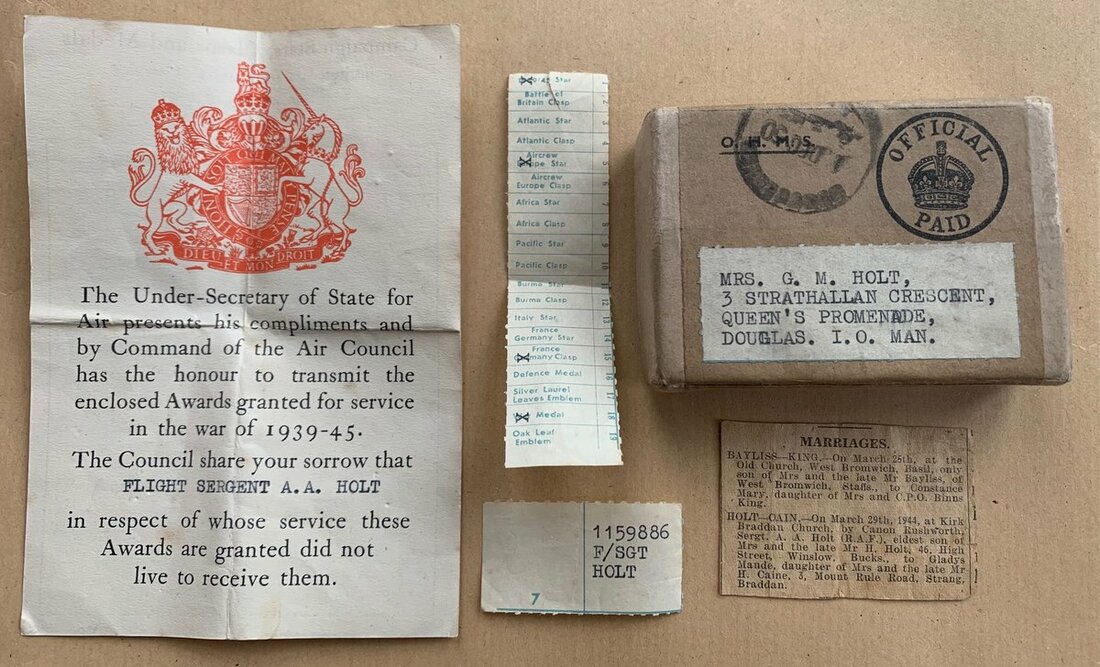

1939-45 Star; Air Crew Europe Star, clasp, France & Germany; War Medal 1939-45, with Air Council enclosure in the name of 'Flight Sergeant A. A. Holt', ticker tape named '1159886 F/Sgt Holt' and card box of issue, postage for 1 December 1950 and addressed to 'Mrs. G. M. Holt, 3 Strathallan Crescent, Queen's Promenade, Douglas. I. O. Man.', nearly extremely fine (3)

Purchased from a jeweller in the north-west soon after the death of Holt's widow (who never re-married) in 2005.

Albert Arthur Holt was born on 13 January 1915 and lived at Winslow, Buckinghamshire. He never knew his father, Harry, or uncle, Frederick, both of whom had been killed on active service in France, so it fell upon his mother Florence to bring up her two sons.

In July 1940, Holt enlisted in the Royal Air Force, his brother followed suit joining the Royal Corps of Signals. After initial training at Cardington, Holt was promoted to Temporary Corporal, mustered into the trade of Ground Gunner and in October 1941 arrived on the Isle of Man. It was a posting that would change the life of a local girl, Gladys Maude Cain, whom he would later marry.

Although the RAF Regiment wouldn't be formed until February 1942, the need for airfield and perimeter defence was well established within RAF doctrine. In order to feed the need for trained personnel the Ground Defence Gunnery School had been established in late 1939, taking up residence at Ronaldsway Airfield on the Isle of Man in July of the following year. Having completed his gunnery training Holt was next posted to the airfield at Jurby.

On 7 November 1942 he reported to the RAF's Air Crew Reception Centre (ACRC). If proof were needed that recruits had entered a different world to their infantry counterparts it was to be found here. Headquartered at Lord's Cricket Ground the ACRC billeted recruits in nearby Abbey Road whilst meals were taken in the canteen of Regents Park Zoo. Holt was selected for training as an Air Gunner and headed to 14 Initial Training Wing (ITW) at Bridlington. After square bashing, PT and kitting out he made his way to 7 Air Gunnery School (AGS) at Stormy Down. Once qualified as an Air Gunner his next stop was to16 Operational Training Unit (OTU) at Upper Heyford. Here Albert would join the other trades required to crew a bomber aircraft, a process that was conduced with typical eccentricity.

Rather than consider aptitude, personality or other attributes that could make an effective crew the RAF simply put all newly qualified men into a hanger with tea and biscuits. It was for individuals to assess their contemporaries and arrange themselves into the required mix. By such simple methods a man's fate would be sealed. At the end of the process Albert emerged as part of the crew formed by Liverpudlian pilot Thomas Vincent O'Shaughnessy.

The crew formed up as follows:

Pilot: Pilot Officer T. V. O'Shaughnessy

Navigator: Pilot Officer A. D. Holding

Air Bomber: Pilot Officer G. A. Kendrick

Wireless Operator: F/Sgt A. G. J. Ward

Mid-Upper Gunner: Sgt A. A. Holt

Rear Gunner: F/Sgt J. W. Hutton

Although the crew would bond together over the following two months it would not be until arrival at 1160 Heavy Conversion Unit (HCU), Swinderby that the team would be complete. Here they would acquire their final member, Sgt D. G. W. Stewart, a Flight Engineer.

First Operations

On 15 June 1943, O'Shaughnessy's crew arrived at RAF Woodhall Spa, near Lincoln. The airfield had only been completed the previous year and was situated close to the small town from which it took its name. Here they joined No. 619 Squadron, a unit that at the time of their arrival was only two months old. It was with this unit that the crew would begin their operational tour and the aircraft they would be flying was the legendary Avro Lancaster.

The crew flew their first operation to Cologne on 28 June. Other operations quickly followed, minelaying on 1 July and a return trip to Cologne a week later. It was however a mission to Turin on 12 July that would test the crew's efficiency.

Baptism of Fire

Having taken off from Woodhall Spa at 2255hrs the crew were just over one and a quarter hours into into their mission and flying at 18,000 feet when from his rear turret F/Sgt Hutton spotted an approaching night fighter. Quickly identifying it as a Messerschmitt 110, he observed it approaching from the rear port quarter, crossing abeam towards the Lancaster's starboard beam. As the enemy aircraft turned in to attack, Hutton instructed O'Shaughnessy to instigate a dive to starboard. At the same time Holt opened fire, continuing to engage the enemy at a range of around 200 yards until it broke away to port, being lost to view in the darkness. The two gunners fired a total of 200 rounds and although they made no claim to having destroyed the aircraft they did believe that hits had been scored to its nose area. Whether or not this was the case the crew had proven their ability to work as a cohesive team, driving off an attacker and sustaining no injuries.

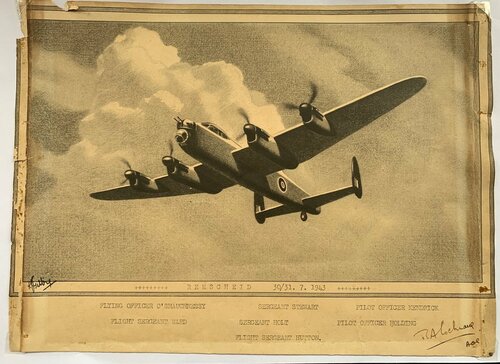

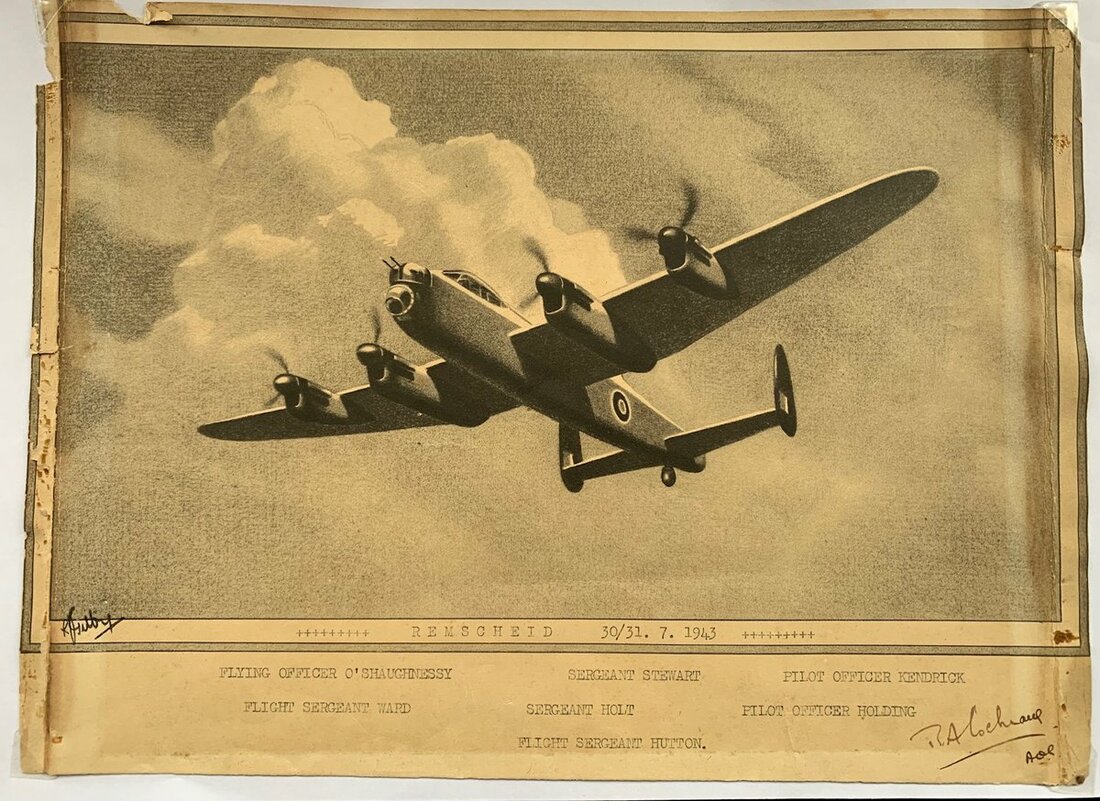

Over the following month the pace of operations steadily increased, operations were mounted to Hamburg (twice), Essen and on the night of 30/31 July on a mission to Remsheid the crew received a coveted 'Aiming Point Certificate.' As bombs were dropped over a target a flash photograph would automatically be taken. These assessed both a crew's efficiency and the general effectiveness of bombing accuracy. The Certificates had real status and were invariably signed by the Group Commader, in the case of O'Shaughnessy's crew, this was Air Chief Marshal Sir Ralph Alexander Cochrane.

In the coming weeks Holt flew missions to Milan, Nurnberg, Berlin and Mannheim but for a reason as yet to be established he stood down for two operations. These were the well documented raid on the V weapons development facility at Peenemunde on 17 August and another to Berlin five days later. This wouldn't have been a decision taken lightly, crews were generally a superstitious bunch and viewed any change in 'line up' with dread. More importantly this put Holt out of step with his crew and as the time to rest was measured by the number of missions flown he would have to make up the shortfall by flying with other crews.

It's an old adage that war is long periods of boredom punctuated by intense bursts of activity and it's also true that most Air Gunner's would never fire a shot in anger. If Holt harboured any thoughts that his moment had come and gone they would be dispelled on 6 September.

Another eventful night

A bomber crew were at their most vulnerable as they made their run in towards the target. To give the Air Bomber his best chance of placing the payload on target it was necessary to fly straight and level. Silhouetted against the burning target below and at the risk of being picked up by a searchlight beam the aircraft was at risk from both ground and air defences. As the crew commenced their bombing run over Munich, Holt spotted a single engined Focke-Wulf 190 approaching from dead astern. There had been no warning from the Lancaster's rudimentary radar ('Monica') and the fighter had closed to within 200 yards before Hutton opened fire whilst simultaneously instructing his pilot to dive port. As the fighter made its attack, Holt joined in the firing. Hits were seen by both gunners and at debrief they would claim the fighter as 'damaged'. The debrief was however hours away and their mission was far from over.

As the crew made their way home at 22,000 feet a white flare was seen to burst at the same altitude slightly to port and roughly on the aircraft's projected track. From his rear turret Hutton once more gave an instruction for the aircraft to dive port. This time the attacker was a Me109 approaching from below slightly astern of port. As he shouted the warning Hutton opened fire, with the enemy returning fire from a range of approximately 400 yards. Thankfully O'Shaughnessy reacted quickly and the attacker's tracer was seen to pass below the Lancaster. As the flare extinguished itself the fighter was lost to view and no further attacks were encountered. After almost 8 hours in the air it must have been a relieved crew that touched down at Woodhall Spa. Once again they had proved their mettle in combat.

The crew had by now flown 16 missions and driven off three night fighter attacks, with the Aiming Point Certificate they'd also proved their accuracy. It was unsurprising that they'd attract the attention of headhunters from other Squadrons. As No. 617 Squadron prepared to move from their temporary home at Scampton into more permanent accommodation at Woodhall Spa, their scouts were on the look out for suitable crews. The O'Shaughnessy team was exactly the sort of material they were seeking.

'Dambusters'

Known then, and now, as 'The Dambusters', No. 617 Squadron need little introduction. Although originally formed to be a 'one Op' unit, the Squadron had subsequently been embedded within Bomber Command. Their specialism was to be accuracy and on 30 September 1943, four months after the Dams Raid, O'Shaughnessy and his crew became members of what was at the time probably the best known Squadron in the RAF's relatively short history.

His first operation with the Squadron would be to attack the Antheor Viaduct, it would however be overshadowed by news from the Aegean, with his brother going 'in the bag' at Leros.

Death of the Captain, death of a friend

Worse news was to come. On 20 January 1944 O'Shaughnessy was killed in a flying accident. Holt had not been required on the flight but their Navigator Pilot Officer H.D. Holding , Wireless Operator F/Sgt A. G. J. Ward and Air Bomber Pilot Officer G. A. Kendrick had been on board. A broken leg was Ward's souvenir of the accident whilst for Kendrick it would be a long road to recovery. Tragically Holding had been killed outright. O'Shaughnessy was buried in Liverpool on 25 January, Holt, Hutton and Stewart went to represent the Squadron. The funeral also marked the crew's disbandment. In the weeks following O'Shaughnessy's death Holt flew 3 Ops with two different crews.

For most of the war a standard tour of operations in Bomber Command comprised 30 missions, a second tour being reduced to 20. For special Squadrons the number rose to 45 and after D-Day it was decided that daylight raids over France would only count as half a mission. Returned to the Isle of Man where he married his sweetheart, Gladys, on 29 March 1944, still only half way to a full Tour. A few weeks later, another singleton had arrived on the Squadron and he was in need of a crew.

Reid V.C.

On the night of 3 November 1943, Acting Flight Lieutenant William 'Bill' Reid (Medals sold in these rooms, November 2009) was a member of No. 61 Squadron who had been detailed to attack a target in Dusseldorf. Shortly after crossing the Dutch coast, Reid's aircraft was attacked shattering the pilot's windscreen. Despite being wounded in the head, shoulders and hands and with controls badly damaged Reid had continued to his target. His determination to complete his mission in the face of repeated enemy assaults, together with his outstanding airmanship in bringing the badly damaged aircraft safely home, led to the award of a Victoria Cross.

Once he had recuperated from wounds sustained that night, Reid was posted to No. 617 Squadron. A mission to Juvisy on 18 April saw Reid cement his new crew. Not only was Holt appointed as mid-upper gunner, his friend and comrade Stewart, who had not been required on the fatal training mission due to the presence of a second pilot, was brought along as their Flight Engineer. Most reassuringly the ever vigilant Hutton, now promoted Warrant Officer, was back in his 'office' at the rear turret. The crew formed up as follows:

Pilot: F/Lt W. Reid VC

Navigator: J. A. Peltier

Flight Engineer: F/Sgt D. G. W. Stewart

Air Bomber: P/O L. G. Rolton

Wireless Operator: F/O D. Lucker

Mid-Upper Gunner: F/Sgt A. A. Holt

Rear Gunner: W/O J. W. Hutton.

In the run up to D-Day the crew flew Ops on La Chapelle, Brunswick and Munich. Their greatest operation would however be flown on the eve of the invasion.

D-Day

On the night of 5 June 1944, as D-Day was imminent, over a thousand British aircraft were in action over the Channel. During the previous days, there had been co-ordinated attacks on coastal batteries and radar stations, all the time being painstakingly careful not to give any clues to the location of the forthcoming invasion.

On the day of the invasion, allied planes dropped tons of aluminium foil strips called "chaff" in order to deceive enemy radar into thinking that an invasion air force was heading in the Pas de Calais region. The Squadron were allocated the central role in 'Operation Taxable'. This was intended to create a detailed and credible diversion, simulating an invasion fleet on enemy radar screens. Intelligence reports were confident the enemy was convinced the invasion would take place in the vicinity of Calais. The RAF action further reinforced this belief. Group Captain Leonard Cheshire No. 617 Squadron's effort whilst No. 218 Squadron carried out 'Operation Glimmer' nearby.

The plan was to create the impression of a grand invasion fleet of ships moving at 8 knots towards the coast of France at Cap d'Antifer which was approximately 60 miles east of Normandy. The first wave of Lancasters took off from Woodhall Spa at 2300hrs on 5 June and began their precision movement off the Sussex coast. Eight aeroplanes had to fly in line abreast at 180 mph, with 2 miles separation between each aircraft, jettisoning reflective material known as 'Window' in timed bundles. After flying in this manner for exactly 2 minutes, all eight aircraft would then turn 180 degrees away from the English coast for a repeated parallel run. After two hours, the second wave took over, making sure to carry on the sequence without interruption or deviation so the enemy's radar imagery would remain consistent in its representation of the 8 knots progress. This whole operation was carried out, of course, in total darkness. Meticulous accuracy in navigation and flying resulted in a successful operation, maintaining the vital deception of the invasion force directed at the Pas de Calais.

It's not clear from the ORB which wave Reid's crew formed a part of but in order to maintain a consistent flow of 'Window' two extra crew members were carried.

For the rest of June Holt flew an Op every other day and a well earned rest was awarded at the end of the month. When the crew returned from leave none of them would have realised that the next operation would also be their last.

Journey's end

On 31 July 1944, both No. 617 and No. 9 Squadron were detailed to attack a railway tunnel at Rilly-La-Montagne near Rheims. The tunnel had been converted for use as a V-rocket storage facility. It was a high priority target and the attacking aircraft were armed with 12,000lb 'Tallboys', a bomb designed to penetrate the ground and create an earthquake effect on detonation.

With two Squadrons over a small target the airspace was crowded, as Rolton pressed the bomb release button Reid felt the aircraft shudder. Witnesses would later state that a bomb, released from above, had struck the aircraft which broke in two. By some miracle Reid and Luker were thrown clear. The rest of the crew, including Holt, perished. He was buried in the Clichy Northern Cemetery.

Before her death in 1968, his mother, Florence, deposited a large amount of correspondence with the Imperial War Museum. This archive weighs in at over 4kg and includes letter the letter from Reid quoted above this Lot, date 20 June 1945; sold together with his Aiming Point Certificate, signed by Cochrane and copied RAF Service Record.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£750

Starting price

£350