Auction: 21001 - Orders, Decorations and Medals (conducted behind closed doors)

Lot: 413

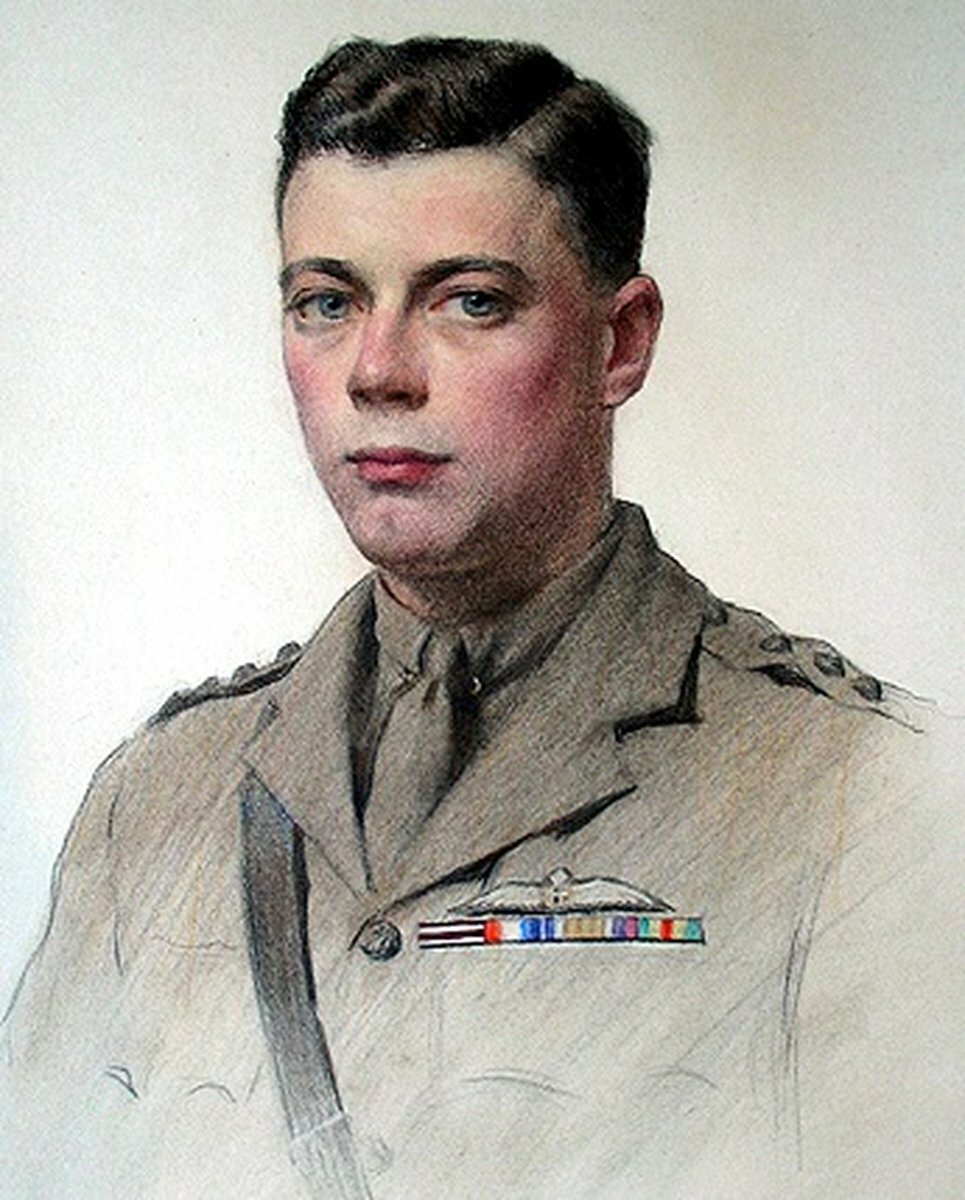

An impressive Great War D.F.C. group of five awarded to Captain H. N. 'Nog' Loch, Royal Air Force, Royal Welch Fusiliers and 5th & 8th Gurkha Rifles, who won his decoration with No. 4 Squadron in France in 1918

Distinguished Flying Cross, G.V.R.; 1914-15 Star (Lieut. H. N. Loch. R. W. Fus.); British War and Victory Medals (Lieut H. N. Loch. R.A.F.); General Service 1918-62, 1 clasp, Iraq (Capt. H. N. Loch.), mounted court-style for display by Spink & Son, St James's, London, cleaned, very fine (5)

D.F.C. London Gazette 3 June 1919 (France).

Humphrey Norman Loch was born at Muttra, India on 11 November 1895 and educated at Marlborough College. Commissioned into the Indian Army on 15 August 1914, he served in France with the Royal Welch Fusiliers from 31 March 1915-8 September. Transferred to the 8th Gurkhas, he saw action in Mesopotamia from 6 September-18 October 1916. Loch thence joined the Royal Flying Corps and underwent training in Egypt. A letter to his brother on 8 December 1916:

'This is not a bad spot. Top hole weather, the sea quite near and Alexandria not far off to go and have a fairly decent time in when one can. I've done about ten hours flying all told, about one and a half hours on my own i.e. without an instructor. It's not bad fun now I'm getting used to it. It's not frantically interesting as you don't see much but clouds unless you've got your neck screwed over the side the whole time. There are a lot of rather queer specimens in this show but they are not bad taken all round.'

Further details from Framlington Aerodrome, 7 February 1917:

''We arrived alright last night and have got quite a comfortable billet together with a very decent old thing who looks after us very well. It is most horribly cold and flying is horribly freezing. I was distinctly out of practice when I went up this morning. It's not such a bad little spot this. They have the most extraordinary machines here, very good for strafing the Hun let's hope. We work from 9am 'til about 4:30 but nothing very strenuous. All the rest of our class from Egypt are here, but the worst ones have either been sent elsewhere or are still in Egypt. Send up another woolly waistcoat when you have finished it as Crutchley has not got one. We have to do a good many tests and things and so expect to be here two or three weeks yet.'

His training continued and Loch managed to crash land in a snowstorm soonafter, thankfully managing to escape any serious injury. He was moved south and began with the aeroplane ferrying sorties over the Channel from Lympne. In a letter to his mother:

'DH.4 No A4714 St Omer 13th August 1917

I am writing this in a bus on my way back to Lympne. I am passenger so have the use of my hands.

I came over this morning and am on my way back. A wonderful view as we go across France with the Channel in sight. We are now at 3,000 feet and going at 85 mph. The fields and woods stretch out for miles. It's a dull day so it's not as pretty as it might be. Here's Calais on our right and Boulogne miles over on the left. You can just see England.

There was a raid on when I got back last night but none of our people saw anything.

The sun's coming out. The effect above the clouds is very pretty.

Please excuse the writing, the wind's blowing the paper about. We shall be in to the clouds soon. We're now 4,000 feet up and just over Calais. We're over the clouds now in a regular Switzerland of cotton wool.

Now we're over the channel and can see England in the haze. The boats are like little water beetles leaving white trails. Absolutely blue sky above us and down on the ground it's a dull stuffy day. It's getting beastly cold as we are over 7,000 feet now and still climbing.

One man fell in the sea today but was picked up.'

Further extracts track his moods:

Lympne Aerodrome 10th September 1917

'We have had a fairly exiting time during the last week. One night bombed four times in Omer. Boulogne bombed three nights in succession. Also various stray Huns passing over this place. Otherwise everything is as dull as ditch water and most of us are in a state of collapse from utter boredom.

They have sent a lot of us away to various other places in England but being unlucky I've been stuck here. Very sorry to hear poor Crutchley had such a crash, but he's much to be envied with his Russian Order and Captaincy.'

Lympne Aerodrome 31st October 1917

'You may be pleased to hear that I have now flown our great bombing machine the DH.4 and that I've been promised to be allowed to fly the SE5 which is the best scout in use. So things are looking up. I'm liking flying again.

I can hear a Hun machine and there go the guns again. They'll grin on the other side of their faces when our new bombing busses are released from the entanglements of red tape and get at them.'

Filton Aerodrome 16th November 1917

'I am flying a Bristol fighter and like it. The aerodrome or rather the mess here is top hole. Bristol is quite a good spot and I'm not keen on rushing back to Lympne so am in a way glad the weather's dud.'

The period which covers the award of his D.F.C. is related thus:

'Bad weather was a nasty trial. But in addition to ranging guns, we had a multitude of other duties such as night reconnaissances, short day reconnaissances, photographing, dropping bombs, machine gunning the ground and flying low along the front line to keep in contact with the infantry. Before returning after each shoot, we were supposed to drop our bombs and loose off a few rounds of machine gun fire into the enemy back areas. What good this ever did, I do not know. No doubt it was one of the ultimate reasons why we are supposed to have won the war i.e. we did more useless things and encouraged more waste than the Germans.

Occasionally the tedium of a shoot was broken by the appearance of enemy aircraft. Perhaps one was attacked. But if one had a wakeful observer this never needed to happen as we were permitted, even encouraged, to keep out of the way of aerial combats. Few of us deliberately broke this rule. Nor did many of us attack the enemy balloons which were so thoughtfully strung along the enemy back areas. Sometimes a dare devil pilot who had even been known to loop an R.E.8 and come out alive, did actually bring down a balloon or an enemy scout. But for the most part we attended strictly to our own business and left the long bombers and the scouts and the fighters to do whatever dirty work they pleased without giving them the faintest cause to imagine we were trespassing on their preserves.

The tranquillity of my existence was only disturbed when I got more than one shoot to do a day, had to go on a night reconnaissance - which I loathed - and finally when a solitary Bristol Fighter was introduced to the squadron for the purpose of carrying out special long range shoots with nine point two guns on special mountings for harassing back areas. For these shoots one had to get up to a greet height - for an artillery observer who spent most of his flying life between five and three thousand feet - and wireless telephony was introduced. This machine was also used for long reconnaissances and it was on these solitary flights that one used to get into trouble as the enemy scouts, which never patrolled in numbers less than three, were always ready and waiting to gulp up a solitary two seater. On one occasion after looking for some time at the faint smoke coming from the muzzles of three elegantly painted machines, I noticed what I took to be the smoke of a fire in our engine and hastily went into a spin. Fortunately it proved to be only steam from a bullet pierced cylinder. However I was glad to be out of it as my machine was well shot up and my observer wounded. On another occasion, thinking to gain a little cheap glory, we attacked a scout which was sitting on the tail of an R.E.8, and hearing the unpleasant noise of machine guns not my own, looked around and found myself the objective of half a dozen German comrades. Once again my unfortunate observer was wounded, this time very badly and I side slipped out of the fray.

The advance began and presently, we left St Omer and dumped ourselves down on Linselles not far from Lille. This had been an old German aerodrome. The wooden hangers were pierced with the machine gun bullets of raiding scouts and the field was dotted with the tails of twenty pound Hale's bombs which had been dropped from a low height and failed to explode. We erected canvas hangers and were billeted among the small houses which surrounded the aerodrome. Here it was that we did our last war flying helping to tickle up the stern of the German army as it retreated. The armistice came, heralded with the blowing off of numberless Very lights. We could not believe it. I forgot to say that we did not move direct to Linselles. First we went to an aerodrome at the foot of Mt. Cassel and life became distinctly lively as we had to work in bad weather and the advance was causing us to have casualties frequently. At least two of our machines were blown to pieces by our own shells.

From this aerodrome, we moved I think to Ronq near Lille where we did no flying but had a busy enough time trying to keep from freezing to death. For this purpose we had to cut down all the wooden telegraph poles in the neighbourhood. I had a very nice billet here, in the house of an old officer. Our chief amusements here were low flying and exploring the Lille Fort and neighbourhood. I remember a monument to the Germans who fell at the taking of it. It was a curious heterogeneous life at this time. I do not clearly remember where we slept or ate. Linselles however is quite clear. We had our own squadron Mess run by me and a very economical Mess it was. We tried the experiment of a French cook but she did not last long. I limited the amount to be paid for Messing to a Franc a day and we did darn well on it. This I think was my greatest achievement in the war. This was all after the armistice. We used to fly to St. Omer for our provisions and bring them back in the machines.

Another of our diversions was trying to shoot wild duck from the aeroplane with the aid of a walking stick .410 shot gun. There was a great lake on the Lys near Bailleul which was covered with duck. Davidson and I would dive at the duck until we were almost touching them and then do spiral turns round them as they rose. But they soon beat us as they could do tighter climbing turns than we could and after a while they even refused to be driven into the air until our wheels were wet. We never brought one down.

Another diversion was going over the battlefields, exploring the huge defence lines round about Linselles, part of the Hindenburg Line. We visited the Messines ridge and saw the havoc of the heavy fighting there. We visited the Ypres salient, passed the great craters of enormous mines, aeroplanes crashed in shell holes, tanks stuck in the mud and disembowelled. Indescribable the effect the memory of all this has. At the time one was callous and saw every new horror with a casual eye.

The war over, the squadron started to break up. Some of us went off to Germany, some went home and some went to other squadrons elsewhere. I put in for a Hindustani course and was sent to Rouen for six excellent months, passed at the R.A. base depot on the edge of the great forest. It was a fine life, with horses to ride, the woods to explore and nothing much to do except drink and make merry.

Alas, in the end they found me, sent me to some camp near St Omer and shipped me home in a deplorable condition to Manston Camp where finally I was given the choice of becoming a pukka RAF officer or returning to my regiment. I decided on the latter as the indiscipline and disorganisation of the RAF at Manston disgusted me. It was perhaps a foolish decision.'

Having duly added the laurels to his record, Loch returned to the Indian Army and rejoined the 5th Gurkha Rifles for the operations in Mesopotamia. He was in Command of 'B' Company when the unit, numbering 12 Officers and 742 Gurkha other ranks left Kakul on 14 September 1920. He was with his Company when they came under heavy fire during the action at the Iman Abdulla Bridge on 20 October (History of the 5th Royal Gurkha Rifles: 1858 to 1928, Colonel Weekes, refers).

Retired from the Indian Army, he married and took up work which took him to North America and the Far East, eventually settling in British Colombia. Loch died at Coquitlan on 3 August 1977; sold together with copied research.

Loch started writing Short Precis of Years 1914-1930 which remained unpublished. Extracts of his letters have been published via http://www.flyingclothing.co.uk/pg006.html which is maintained by the grandson of Captain G. G. Crutchley, a close friend of Loch.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£2,700

Starting price

£1200