Auction: 20002 - Orders, Decorations, Medals & Space Exploration

Lot: 591

A particularly fine 1941 'Air Fighting Development Unit' A.F.C. group of eight awarded to Group Captain B. L. Duckenfield, Royal Air Force, who flew Hurricanes during the Battle of Britain and shot down three enemy aircraft

During those fateful weeks in the summer of 1940, Duckenfield flew on Adlertag ("Eagle Day") - 13 August 1940 - when the full force of the Luftwaffe was thrown at RAF Fighter Command in their attempt to take the skies over Britain; it was the men like Duckenfield who secured the Allied victory

Fortunate to survive two crash-landings, firstly as a passenger in a transport aircraft, secondly as Pilot in a Hurricane with a failed engine, his career spanned the highs of the Air Fighting Development Unit - where he delighted in flying captured Me.109, Me.110 and Ju.88 aircraft - and the lows of two years' incarceration in Japanese hands in Rangoon Jail having been downed following a raid on Magwe

Liberated in May 1945, he returned to a highly successful career as a Jet Pilot, later serving Rolls Royce with distinction in Japan; a country which he learned to love and respect, despite all he had faced as their captive

Air Force Cross, G.VI.R., reverse officially dated '1941'; 1939-45 Star, clasp, Battle of Britain; Air Crew Europe Star; Burma Star; Defence and War Medals 1939-45; General Service 1918-62, 1 clasp, Malaya (Sqn. Ldr. B. L. Duckenfield. R.A.F.; Coronation 1953, minor contact marks, very fine (8)

A.F.C. London Gazette 24 September 1941. The official citation - awarded whilst serving with the Air Fighting Development Unit, No. 12 Group - states:

'This officer has shown consistent and exceptional ability as an air fighting development pilot since joining the unit in September 1940. He has flown many types of aircraft in tactical and armament trials, sometimes at night. In particular he has participated extremely well in the development trials on new American aircraft. He has at all times shown an outstanding devotion to duty and his accurate flying and recording of results have assisted materially in the speedy and successful conclusion of the trials.'

Byron Leonard 'Ron' Duckenfield was born on 15 April 1917 at Sheffield, the son of Leonard and Ann Duckenfield of 49 Marcus Street, Sheffield. Of good working-class stock, his father was a fishmonger's assistant before serving as a cavalryman in Mesopotamia during the Great War. Similarly, young Ron grew up among the terraces and was educated at the Cathedral School - where he demonstrated an aptitude for languages - later working for a brief period as a milkman's assistant (The Daily Telegraph, refers).

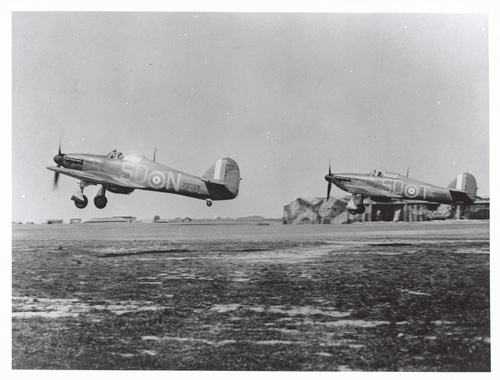

Duckenfield joined the Royal Air Force on 25 November 1935 as a direct-entry Airman Pilot and commenced his elementary flying training at the Civil Flying Training School at Brough. Sent to Depot at Uxbridge on 18 January 1936 and on to No. 10 F.T.S. at Ternhill from 2 February 1936, he successfully passed the six-month course and was posted to No. 32 Squadron, Royal Air Force, at Biggin Hill on 8 August 1936. Accordingly, these must have been happy times for Duckenfield as he remained with No. 32 Squadron for a considerable period of time, likely flying Bristol Bulldog and Gloster Gauntlet aircraft before conversion to the Hawker Hurricane in October 1938 (Air of Authority - A History of R.A.F. Organisation, refers). Developing a love of Sir Sydney Camm's brainchild, Duckenfield was still serving with No. 32 Squadron at the outbreak of the Second World War.

Exalted Company

Commissioned on 1 April 1940, Duckenfield transferred to No. 74 Squadron at Hornchurch eleven days later, before moving to No. 501 (County of Gloucester) Squadron at Tangmere on 5 May 1940 which was similarly equipped with Hurricanes. During the course of the war, No. 501 Squadron could lay claim to numbering some of the finest fighter pilots of a generation, including Sergeant Pilot Antoni (Toni) Glowacki, V.M., C.V. & 3 Bars, D.F.C., D.F.M. - who shot down five German aircraft on 24 August 1940 to become the first of only two pilots to achieve 'Ace in a day' status during the Battle of Britain - and James Harry 'Ginger' Lacey, D.F.M. & Bar, who became the second highest scoring fighter pilot of the Battle of Britain, credited with 28 enemy aircraft destroyed, five probables and nine damaged.

With orders to reinforce the air component of the B.E.F., No. 501 Squadron flew to France on 10 May 1940, Duckenfield following the following day with the rear party in Bombay L-5813. All seemed well until the transport came into land; as Flying Officer Frederick P. J. McGevor, D.F.M., prepared to touch down on the Marne at Betheniville Airbase the aircraft's nose inexplicably went up and the pilot decided to go around again. On the second approach the same thing happened, with McGevor appearing to lose control. The aircraft stalled and crashed into a field just short of the runway, the accident resulting in the deaths of four of the fifteen persons aboard. Likely wheeled away in a makeshift trolley or dragged along the ground on a piece of wreckage, Duckenfield was treated at the Casualty Clearing Station at Epernay and then sent back home to Roehampton Hospital in south-west London. Briefly surrounded by some of the foremost Champagne Houses in all of France, he later ruefully acknowledged:

'On my first visit to France, my feet never touched the ground.'

His mood was likely darkened further by the popularity at that time of cod liver oil - seen as a 'cure all' and ideal for joint problems - perfect for when one has been extricated from the mangled wreckage of a No. 271 Squadron transport.

Posted to No. 1 R.A.F. Depot at Uxbridge on 19 May 1940 as non-effective sick, Duckenfield finally returned to No. 501 Squadron at Middle Wallop on 23 July 1940 after a period on convalescence. Flying from Hawkinge on the Kent coast he was soon in action and shared in the destruction of a Stuka dive-bomber over Dover on 29 July 1940 flying Hurricane P3646. Eleven patrols later he intercepted 30 Ju87's over Hawkinge on 12 August 1940, followed by a further 30 Me110's and Me109's that same afternoon. He rounded-off the day with a fifth patrol over Gravesend at dusk, likely exhausted after three hours at the controls. This relentless taking to the skies and consequent pilot fatigue was later described in vivid detail by Squadron Leader Geoffrey H. A. Wellum, D.F.C., in his much acclaimed wartime memoir 'First Light' which detailed similar experiences with No. 92 Squadron during the Battle.

On 15 August 1940, Duckenfield successfully intercepted 45 Dornier aircraft, his log book noting 'Detling. One Dornier 215 damaged, probable'. A second scramble that afternoon resulted in the interception of over 200 enemy bomber and fighter aircraft and the confirmed 'kill' of a Dornier Do215 over Tunbridge Wells. Flying almost daily as the Battle intensified, Duckenfield achieved another victory over Sheerness on 28 August 1940, his log noting 'One Me109 destroyed, confirmed'. Meeting further swarms of bombers over Kent and Sussex, he bagged a further confirmed Me109 over Folkestone on 8 September 1940, before taking a remarkable thirteen separate 15-minute flights two days later between Kenley and Gravesend in Hind L7226 with Sergeant Raymond J. M. Gent - who was fresh from shooting down an Me109 himself on 5 September 1940. Mentioned in Despatches, Duckenfield took his final flight with No. 501 Squadron on 12 September before being transferred to the Air Fighting Development Unit (A.F.D.U.) at Northolt.

Hanging in the balance

Formed just a month earlier, Duckenfield joined an embryonic unit led by Wing Commander G. H. 'Tiny' Vasse and with Squadron Leader Ian Campbell-Orde as second in command. Implicit in the title, the A.F.D.U. aimed to tactically evaluate new allied aircraft against captured enemy aircraft, the aim being to garner as much information as possible in order to train Allied bombers crews in meeting German and Italian fighter attack. Other associated tasks involved exploring photography for training purposes and tactically testing various types of new equipment and armament. For Duckenfield, what initially looked like a 'boys with toys' opportunity, was nothing of the sort; one must remember that at this time the losses experienced by Fighter Command were proving critical with large numbers of badly burned men being admitted to the Queen Victoria Hospital at East Grinstead. Others, such as Sergeant Ernest Scott of No. 222 Squadron - credited with an impressive tally of nine aircraft destroyed, shared destroyed or damaged - were taking off on patrols never to be seen or heard of again until discovered buried beneath an orchard some fifty years later (Finding the Few, refers).

Replacing such experienced pilots was proving extremely difficult, the circumstances of September 1940 being starkly delivered by Laurence Olivier in the highly-acclaimed film The Battle of Britain (1969):

'The essential arithmetic is that our young men will have to shoot down their young men at a rate of four to one, if we're to keep pace at all.'

In consequence, any tactical trials which might find an advantage over the enemy were of vital significance - irrespective of whether the knowledge gleaned might be put to work in Fighter or Bomber Commands - and Pilot Officer Duckenfield was at the very forefront.

'The Most Rewarding Year of my R.A.F. Career'

One of Duckenfield's first projects involved co-operating with the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough and conducting flare trials which aimed to counter the Luftwaffe's increasing number of night attacks. Acting as Second Pilot in Blenheim P4899 with Squadron Leader Clouston in command, Duckenfield flew three separate sorties from 24-25 September 1940 whereupon he flew above a simulated enemy bomber, illuminated it with a one-million candlepower flare which was held under each of his wings, and thus facilitated a Hurricane aircraft to latch onto the enemy and theoretically shoot it down. The whole concept sounded so easy on paper, but the planners failed to take into account that the 'real' enemy might have something to say about their manoeuvres:

'The site for the trial was Silloth, near Carlisle, judged to be remote enough to minimise the prospect of enemy interference. But we were not so lucky; just as the Havoc (sic) ignited a flare, illuminating not only the Whitley target, but, incidentally, the whole of Silloth airfield below, an enemy aircraft which happened to be in the area took advantage of our unwitting helpfulness and dropped his bombs. These, fortunately, missed the airfield proper, but fell into the upwind sewage farm, thereby generating an all-enveloping stink over the camp complex. Thereafter, we were banished from Silloth by an irate station commander and had to go farther afield to Aldergrove for future trials' (A Pilot Remembers, A.F.D.U. in 1941, by B. L. Duckenfield, refers).

Duckenfield's Log Book confirms that he and his fellow crewmen were indeed persona non grata at Silloth, the flare trials being abruptly ended. Instead, he tested the cannon of Spitfire R6904 on 26 September and spent the remainder of the month in the West Country. In October he returned to Northolt and began a series of comparative trials involving dessicated and non-dessicated prismatic sights. These were followed by gyroscopic sight trials in Hurricane L1563, following which Duckenfield was allocated the task to take up a series of enemy aircraft to determine their capabilities. It was a role he relished.

At the controls of the enemy

The first enemy aircraft to arrive reasonably intact at the A.F.D.U. was a Fiat CR42, which had landed on the Norfolk coast in November 1940 during the only Italian raid on the United Kingdom. Described by contemporary sources as a 'delightful aeroplane to fly', being very light and responsive on controls, it was nevertheless an already obsolete biplane, completely outclassed by R.A.F. fighter aircraft. On the other hand, the Me109E was proving a formidable enemy. On 27 October 1940, Duckenfield had the opportunity to take one up, his Log Book noting 'Messerschmitt 109. AE479, Experience on Type'. Duckenfield's account notes comparable performance in fighter aircraft, but the assault on the senses may well have revived memories of Silloth:

'The Me109F was (naturally) much superior to the "E". Whereas the latter had been comparable in performance to the Mk. 1 versions of Hurricane and Spitfire, the Me109F was considered superior in speed and manoeuvrability to the Spitfire Mk. V and Hurricane Mk. II.

Both the "E" and "F" versions flown in A.F.D.U. shared one obnoxious characteristic: a strong smell in the cockpit, reminiscent of under-arm body odour. The smell, emanating from the German engine coolant, must have been very powerful originally because it lingered even though the engines were now cooled by R.A.F. glycol' (ibid).

In January 1941, Duckenfield conducted regular cannon trials on Mark V Spitfire aircraft at the Dengie Flats firing range. He followed these with stern and beam attacks on glider aircraft in Hurricane L1563, before testing a captured German sight on 26 January. February and March were spent flying from Duxford on tactical trials in Tomahawk aircraft, the latter involving almost daily cannon firing over The Wash and engine trials. His log book entry for 31 March 1941 notes, '0.5 Gun destruction trial' piloting Tomahawk AH770. As the war progressed however, Duckenfield began to have access to a greater range of captured enemy aircraft - this was the part he truly relished.

Piloting Hurricane Z2448 he challenged a Fiat CR42 in a mock dog-fight at 16,000 feet on 18 May 1941, whilst on 24 August he took to the controls of a Ju88 to analyse the 'slipstream effect' and gain experience of type. On 19 October he piloted a Me109F in a mock dog-fight against a Spitfire VB, and three days later took up a Me110 with Sergeant Reeve over Duxford aerodrome. The fighter-bomber was thoroughly put through its paces by the duo in mock attacks against Spitfire and Wellington aircraft on 23 October 1941. This was repeated on 25 November and 18 December 1941 when they flew the Me110 against Hurricane and Fulmar aircraft. In consequence of these successful trials, Duckenfield was awarded the Air Force Cross:

'My year in A.F.D.U. was one of the most enjoyable and rewarding of my R.A.F. service. As a very junior officer, I was fortunate to be sent to such an interesting and challenging post where, in the space of 14 months, I flew in so many different aircraft types and gained so much valuable experience. The best plane was the Mess 109F.'

Return to action stations

Posted to No. 66 Squadron at Portreath on 20 December 1941, Duckenfield had time to take three local flights over Cornwall and the North Atlantic in Spitfires before serving as part of the '2nd Offensive Cover Wing for seventeen Halifax a/c during (the) bombing raid on Scharnhorst and Gneisenau at Brest' (The recipient's Log Book, refers). This attempt by Bomber Command on 30 December proved relatively fruitless, but it did keep the capital ships 'bottled up' for a short while longer. When the Kriegsmarine did eventually engage Unternehmen Zerberus - popularly known as the Channel Dash - from 11-13 February 1942, Duckenfield found himself busy escorting seven destroyers off the Dutch coast, the Royal Navy likely extremely thankful to have cover from the swarms of enemy aircraft buzzing above Scharnhorst and Gneisenau.

In Command

Following a further nine flights in Spitfire P7299 over southern England, Duckenfield was summoned to Fairwood Common and appointed Commanding Officer to No. 615 (County of Surrey) Squadron on 26 February 1942. He spent the next couple of days between Fairwood Common and Portreath before embarking with his Squadron for Karachi on 19 May 1942. He arrived in early June and soon set about acclimatising and taking short reconnaissance flights in Hurricane aircraft between Jodhpur, Delhi, Allahabad and the Karachi Drigh aerodrome. These were followed by regular armed reconnaissance sorties over Jessore and Agartala and sweeps over the Chittagong Hills on the Burmese border. On 2 November 1942, Duckenfield made an attack on an ammunition dump at Kinyindan, his Log Book noting 'Strikes on 3 huts'. He went on to successfully sink two river steamers flying a Hurricane Mk.2C on 22 November and followed this with a low-level attack at Magwe which left a refinery ablaze and achieved hits on another river craft. Early December witnessed almost daily scrambles and attacks on Naba, Akyab, Buthidaung and Magwe, until finally, his luck ran out.

At first light on 28 December 1942, Duckenfield took off from Chittagong for central Burma to attack the Japanese aerodrome at Magwe, 300 miles away on the banks of the River Irrawaddy. The weather over the target was hazy, but elsewhere visibility was good. Arriving at Yenanyaung, Duckenfield and eleven fellow pilots turned downstream at minimum height and jettisoned their drop tanks before attacking nearly a dozen Nakajima Ki-43 aircraft neatly lined up alongside the runway with a devastating single pass, before withdrawing westward at low level and maximum speed. The subsequent events were later recorded by Duckenfield:

'A few minutes later, perhaps already 20 miles away from Magwe, I was following the line of the chaung (small creek), height about 250 feet, speed about 280mph, when the aircraft gave a violent shudder, accompanied by a very loud, unusual noise. The cause was instantly obvious: the airscrew had disappeared completely, leaving only a spinning hub' (A Casualty Report, refers).

Jettisoning the canopy, Duckenfield considered taking to his parachute but his speed was not sufficient to gain the height required to jump safely. Instead he followed the creek, extended flaps and touched down with the minimum of fuss on the dried-up riverbed. He was extremely fortunate, for December is the height of the dry season in that area:

'I have done worse landings on a smooth runway!'

Nevertheless, once down, the clear skies and lack of cloud cover did impact upon his life quite markedly - for he was spotted coming down by Japanese patrols and was soon captured and sent to Rangoon. Alas, his capture was not by some dramatic manhunt, rather he was betrayed as he entered a small village:

'Nobody seemed surprised to see me (I suspect I had been followed for some time); I was given a quiet welcome, seated at a table in the open and given food. Then, exhaustion took over, I fell asleep in the chair and woke later to find myself tied up in it'.

The next day he was handed over to a Japanese Sergeant and taken back to Magwe, before spending the next two and a half years in the notorious Rangoon jail.

Incarceration

Despite being placed in solitary confinement for large periods of time, Duckenfield attempted to derive some benefits from his time in jail. With his flair for languages he started to teach himself Japanese and over the following two years managed to construct a Japanese/English dictionary; it was the beginning of a long association with the language and the people of Japan. Finally, on 2 May 1945, an R.A.F. reconnaissance pilot flying over Rangoon saw 'Japs Gone' painted in large letters on the roof of the jail. Within days, Duckenfield and a large number of skeletal prisoners were liberated. Perhaps remarkably, his Log Book notes that he flew that very same day as a passenger aboard a Dakota from Pyagi to Comilla - the start of a very long journey home for Duckenfield and 15 others, which would comprise eleven separate flights - before finally reaching R.A.F. Merryfield, near Illminster, on 12 June 1945.

After a long period of recuperation, Duckenfield returned to duty with the Royal Air Force. He joined the British Forces of Occupation in Japan in 1947 and later attended the School of Oriental Studies, where he spent two years studying for a degree in Japanese. In 1950 he returned to flying when he commenced a two-year appointment in command of No. 19 Squadron, flying Hornet aircraft as part of Exercise Emperor. This included dummy attacks on Thorney Island and Odiham and another on Royal Naval vessels positioned off Portland. Transferring to Vampire and Meteor jets at Biggin Hill, Duckenfield took part in numerous aerobatic displays before finally taking a series of more sedate Staff Appointments. He finally retired from the R.A.F. in June 1969, having spent the last three years in the service as the British Air Attache in Tokyo.

Remarkably, Duckenfield wasn't quite ready for the golf clubs just yet. Taking employment with Rolls Royce, he acted as marketing manager for Japan - which enabled numerous return visits to the country which he loved so much. In April 1979 he became the company's senior executive advisor for the Far East and was based in Tokyo for the following three years. His language skills and understanding of the country and its people were a great asset to the company (The Daily Telegraph, refers), indeed he made many friends in Japan and was admired for promoting Anglo-Japanese relations. Ron Duckenfield died in hospital at Burton-on-Trent on 19 November 2010; a son who served in the R.A.F. predeceased him.

To be sold with the following documentation and ephemera:

(i)

Original R.A.F. Pilot's Flying Log Book No. 3, the second page noting in the recipient's own hand, 'Log Books No. 1 & 2 lost at Betheniville, France, 11.5.40.' It then offers an approximate resume of their contents, including a list of Squadrons in which he served from 25 November 1935-23 July 1940, and approximate flight times - including c. 250 hours operational hours - on Hart, Audax, Tutor, Bulldog, Gauntlet, Hurricane and Spitfire aircraft.

The Log Book then offers a full and continuous record of service from 24 July 1940-28 December 1942 when he is posted missing, and then from 2 May 1945-29 April 1952. Well-annotated and displaying his service throughout the Battle of Britain, it includes a number of pasted photographs of aircraft flown and fellow pilots.

(ii)

Original R.A.F. Pilot's Flying Log Book No. 4, commencing with a summary of all flying from 1 January 1946-29 April 1952, followed by a comprehensive full record of service from 1 May 1952-11 September 1965. Incorporating the jet age, this log book displays over 300 flights - the majority as a Meteor or Vampire Pilot - in the Far East and skies of Western Europe. Interestingly, it offers a full list of the Squadrons in which he served, together with dates, and 56 separate types of aircraft flown; in total, a most thorough and fascinating pair of R.A.F. Log Books.

(iii)

An original typed letter from the Central Chancery of the Orders of Knighthood, dated 30 January 1942, inviting Squadron Leader B. L. Duckenfield to an investiture at Buckingham Palace on 17 February 1942.

(iv)

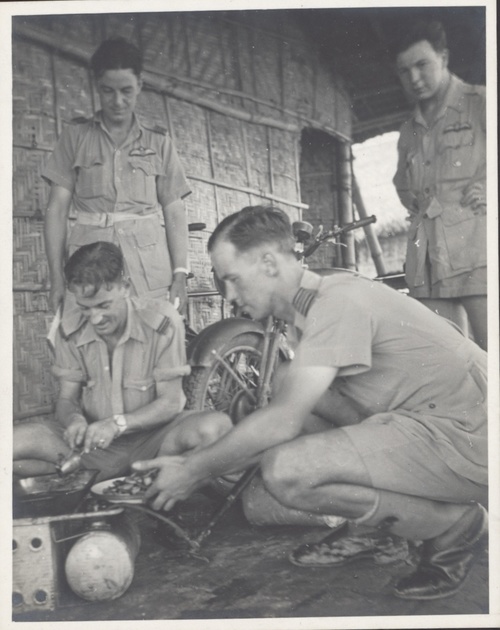

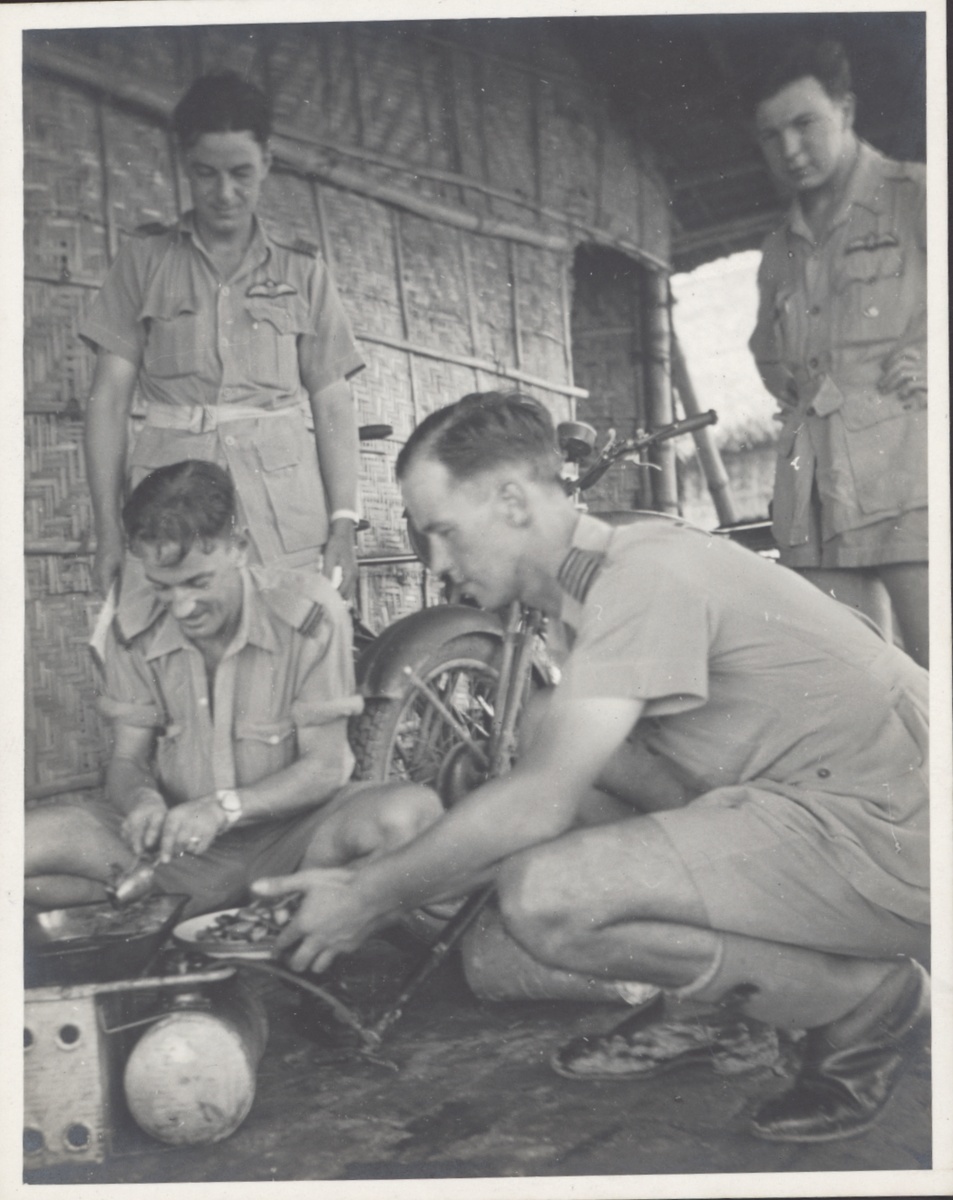

A large photograph album spanning the recipient's pre-war service with No. 32 Squadron, through the Battle of Britain, to Burma, and then as part of the jet age, including some outstanding images of jet aircraft and formal group photographs of Pilots; approximately 45 black & white photographs, many A5 in size and larger.

(v)

Extensive copied research, including Japanese P.O.W. records, the recipient's obituary - as published in The Daily Telegraph - a copied combat report for 29 July 1940, and two original hardback books in which Group Captain Duckenfield is mentioned; Return Via Rangoon and Hurricanes over the Arakan.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£9,000

Starting price

£5000