Auction: 20002 - Orders, Decorations, Medals & Space Exploration

Lot: 589

'My Spitfire was riddled with bullets. One came through the side, took away the throttle and then entered the engine, putting it out of action. I looked down and to my horror I saw two of the fingers of my left hand lying on my lap! There was blood everywhere, petrol was streaming into my eyes and I wasn't at all happy. The controls seemed O.K. so I rolled over, stuck the nose down and beat the hell out of it … '

Arthur Donaldon's hitherto unpublished autobiography, Finger Trouble, refers; a copied typescript is included.

The outstanding Second World War fighter ace's immediate D.S.O., D.F.C. and Bar, A.F.C. group of ten awarded to Group Captain Arthur Donaldson, Royal Air Force

The youngest of the famous Donaldson brothers - all three of whom won D.S.O.s in the R.A.F. in last war - it is said his mother journeyed to Buckingham Palace to attend their assorted investitures on no less than thirteen occasions

Appointed to the command of No. 263 Squadron in February 1941, Arthur commenced a flurry of 'hit and run' strikes to occupied France and Belgium in the unit's Westland Whirlwinds, a period of operations that witnessed his first close encounter with mortality: during a low-level attack on an enemy airfield at Morlaix in September 1941, his aircraft was hit by flak and an explosive round ripped apart the top of his flying helmet

In mid-October of the following year - during his celebrated tour as Wing Commander of Ta Kali, Malta at the height of the siege - he was, as cited above, seriously wounded when his Spitfire was bounced by enemy fighters. In addition to the loss of two fingers, Donaldson was also wounded in the head and feet but somehow got back to Ta Kali to undertake a wheels-up landing: escaping his damaged aircraft in haste - the airfield had just been attacked - he was rushed off to hospital

Yet his woes were far from over, for the Liberator in which he was evacuated from Malta plunged into the sea off Gibraltar; the wounded Wing Commander was among just three survivors

An inspirational leader and a pilot of 'magnificent offensive spirit', Donaldson was nonetheless described in his Times obituary notice as 'a man of great personal charm, kindness and humility'

Distinguished Service Order, G.VI.R., the reverse of the suspension bar officially dated '1942'; Distinguished Flying Cross, G.VI.R., with Second Award Bar, the reverse of the Cross officially dated '1941' and the reverse of the Bar '1942'; Air Force Cross, G.VI.R., the reverse officially dated '1941'; 1939-1945 Star; Air Crew Europe Star, clasp Atlantic; Africa Star, clasp North Africa 1942-43; Burma Star; Defence and War Medals 1939-45; Coronation 1953, mounted as worn, slightly polished, very fine or better (10)

D.S.O. London Gazette 3 November 1942. The original recommendation - for an immediate award - states:

'During the period 11-14 October 1942, this officer participated in engagements against enemy aircraft attempting to attack Malta. Brilliantly leading his formation in attacks on bombers, regardless of the fighters which escorted them, Wing Commander Donaldson played a large part in the success achieved. Attacks on the island were frustrated and several enemy bombers and fighters were shot down. On the 14 October he received wounds in the foot and head and two of his fingers were shot away. Despite this, he flew to base and skilfully landed his aircraft. Wing Commander Donaldson displayed leadership, courage and fighting qualities in keeping with the highest traditions of the Royal Air Force. He destroyed three enemy aircraft, bringing his victories to five.

During the recent battle Wing Commander Donaldson has shown the greatest determination in engaging enemy bombers, on one occasion leading three aircraft in a head on attack on eight enemy bombers, quite regardless of their heavy fighter escort. Another time he led his wing when it smashed up a formation of eight Ju. 88s and 30 to 40 fighters many miles from the coast of Malta. Four bombers and four fighters were destroyed and many more damaged.

The next day he went alone straight through an enemy fighter screen and attacked the bombers and was responsible for the fact that no bombs fell on their target. He was twice shot up and exhibited the greatest skill in regaining base. On the second occasion he lost two fingers on his left hand and had head and foot injuries, yet by unexampled determination he brought his aircraft home. A large portion of the success achieved in breaking up six enemy formations had been due to the magnificent offensive spirit displayed by this officer, and to his outstanding and inspiring leadership. His courage and desire to fight are an example to all.'

D.F.C. London Gazette 2 September 1941. The original recommendation states:

'This officer has shown himself to be an excellent leader and has carried out seven offensive operations against the enemy over Northern France and Belgium. During these operations he has destroyed and damaged a number of aircraft on the ground and inflicted considerable damage to buildings and dispersal pens. Once while returning to base with his squadron, he attacked six anti-aircraft barges, one of which was sunk and three damaged. Squadron Leader Donaldson has by his leadership, gallantry and initiative in action, set an excellent example and is largely responsible for the successful operations carried out by his squadron.'

Bar to the D.F.C. London Gazette 4 December 1942. The original recommendation states:

'Since his arrival in Malta on 8 August this officer has taken part in six patrols, two convoy patrols, one dusk patrol and five sweeps. On 27 August he was responsible for the briefing and leading of the Ta Kali Wing and 185 Squadron which carried out a highly successful low flying attack on three Sicilian aerodromes. He personally chased and successfully attacked a Dornier 127 and caused other damage to military objectives by ground strafing. Throughout the preparation and execution of the whole operation his leadership, careful planning and personal courage were an inspiration to all and greatly contributed to the success of the operation which resulted in the destruction of at least 10 enemy aircraft and the probable destruction of a further nine aircraft over Sicily.'

A.F.C. London Gazette 1 July 1941. The original recommendation states:

'Since 1938 this officer has performed valuable work as a Flying Instructor, and has recently been in command of a Flight for nine months. He has shown marked energy and devotion to duty and has attained a high standard with the considerable number of pupils and instructors he has trained.'

Arthur Hay Donaldson was born at Weymouth on 9 January 1915 and was educated at the King's School, Rochester and Christ's Hospital, Horsham. Having then worked at Metropolitan-Vickers for a year or two, he gained a commission in the Royal Air Force in March 1934.

The outbreak of hostilities found him serving as an instructor at the Central Flying School, in which capacity he was awarded the A.F.C.; he received his award at a Buckingham Palace investiture held on 29 July 1941.

In January 1941, having attended an O.T.U. and converted to Hurricanes, he was posted to No. 242 Squadron at Martlesham Heath. In the following month, however - after several patrols and seeing action - he was advanced to Temporary Squadron Leader and assumed command of No. 263 Squadron, a Westland Whirlwind unit then operating out of Portreath; it later moved to Ibsley.

No. 263 Squadron: Whirlwinds and "Warhead" operations

Donaldson's period of command - which lasted until September 1941 - commenced with regular 'scrambles' and interceptions and it was during one such operation on 1 April that he claimed his first success, a Do. 215 damaged at 8,000 feet over The Lizard; his Wingman was shot down and killed by the Dornier's return fire.

In June, the Squadron commenced a series of "Warhead" operations, crossing the Channel to occupied France and Belgium to attack shipping and airfields. During the first such sortie on the 14th, his Whirlwind was hit by A.A. fire over Querqueville. Further low-level operations followed, Donaldson claiming a damaged Me. 109 off the French coast on 6 August.

Then in late September, he led the Squadron on a strike against Morlaix airfield. It nearly proved to be his last, his aircraft being severely damaged by flak. Finger Trouble takes up the story:

'I remember the intense flak getting uncomfortably close, when suddenly one of them hit me. I felt this one because it was in the fuselage, then a colossal bang and I lost consciousness. It was a funny feeling - rather like a severe blackout. I couldn't see … I remember, all in a flash, thinking "Christ, I'm hit" and my one thought was not of death but of becoming a prisoner of war. I can remember opening the throttle and pulling the stick back. The next thing I remember was gradually coming to. Here again, my sense recovered before my sight and, when I could see, I noticed that I was out to sea, meaning that I had travelled three or four miles at about 300 m.p.h.'

Donaldson continues:

'Then I felt my arm and hand go all wet. I saw that my left hand was covered in blood and the right one was a bit bloody too. I felt blood dripping onto my trousers. My head felt awful. I could not see too well and the noise in my ears was terrific … I climbed to 6,000 feet because I was certain I should have to jump by parachute. I can remember feeling my head and noticing that my helmet was cut in two, and I felt blood too. It hurt one too much to turn around to look and see if I was being chased and anyhow I didn't care … I was glad to see another Whirlwind was with me in open formation. He saw I was hit and was following me home. Every few seconds I felt very feint and sick, and several times I nearly tried to jump, but I pulled myself together in time …'

In fact, Donaldson made it back to base, where he had to remove his parachute before squeezing through a gap in his damaged cockpit. Feeling 'rather groggy', he sat down on the runway to await the arrival of an ambulance.

The national press got hold of his story as he resided at the R.A.F. Hospital, Torquay, a not unhappy period of enforced grounding on account of the mischievous humour of a fellow patient, 'Batchy' Atcherley, one of the famous twins.

Donaldson, meanwhile, was awarded the D.F.C. and took up appointment as Wing Commander Flying at R.A.F. Colerne in January 1942; four months later he was posted to Fairwood Common as Spitfire Wing Leader.

Malta

In August 1942, he was ordered to Malta, where he took up post as Wing Commander Flying at R.A.F. Ta Kali. It was the commencement of a notable tour of duty, the Wing carrying out prodigious work over Sicily, in addition to acting in the immediate defence of Malta.

It was also a tour that witnessed him raising his score to ace-status for, having shared in a probable Do. 217 in late August and a Mc 202 early in the following month, he really went to town in October, as the Luftwaffe mounted its final momentous attack on the besieged island. On the 11th, in a spate of combats north of Grand Harbour, he destroyed a Ju. 88, claimed another as probable and damaged a Me. 109. On the 12th, he destroyed another Ju. 88 and a 109 and on the 13th he damaged a Ju. 88 north of Gozo. Of events on the 12th, he later wrote:

'It was the most spectacular sight I have ever seen. The whole sky was filled with enemy aircraft in severe trouble. I saw three flaming Ju. 88s and another three flaming MEs and counted no less than ten parachutes descending slowly, three of them from a Ju. 88 I had shot down … '

On the 15th, however, disaster struck, but not before he claimed yet another Ju. 88 as damaged. He takes up the story:

'I led an attack on the bombers head on. This split them up and then I followed up with an astern attack on one Ju. 88. My No. 2 and 3 could not follow me, possibly because of their inexperience. I got my sights on the Ju. 88 and smoke and flames came from it. It looked doomed but because I had no one covering my tail I was all of a sudden bounced by enemy fighters.

My Spitfire was riddled with bullets. One came through the side, took away the throttle and then entered the engine, putting it out of action. I looked down and to my horror I saw two of the fingers of my left hand lying on my lap! There was blood everywhere, petrol was streaming into my eyes and I wasn't at all happy. The controls seemed O.K. so I rolled over, stuck the nose down and beat the hell out of it.

I cannot say that at that moment I felt any pain. I was in a state of shock and all I wanted to do was remain alive. As I had dived down I was thinking of what to do. I decided to try and make Ta Kali since if I baled out by parachute it would minutes before the R.A.F. Air Sea Rescue picked me up. However efficient they were, no doubt I would bleed to death before rescue arrived; not only was my left-hand bleeding profusely but I had numerous other wounds to my head, arms, legs and face.

So I turned towards the airfield and luckily I had sufficient height to glide back to it. Luckily also the enemy thought I was a 'goner' and they did not follow up the attack. To this day I do not know what hit me but probably an Me. 109. My undercarriage would not come down and anyway, in case like this, it is safer to land with wheels-up. I could see a certain amount of chaos on Ta Kali aerodrome as it had received a heavy attack.

The airfield was covered with delayed action and incendiary bombs. I had no option but to land and so put the Spitfire down as gently as I could with only one hand. The fire tender was on its way before the aircraft had come to a stop. The gallant crew pulled me out regardless of any danger to themselves. I was told that one of them was awarded a George Medal and well he deserved it. I think by that time the ambulance had also arrived and I was transferred to that and taken to Imtarfa Hospital.

It was about half an hour before I experienced any great pain. I suppose it nature's way of dealing with a severe wound. Within minutes of arriving in the military hospital they put me under an anaesthetic and trimmed up the remains of my left hand. I was of course delirious and I know that I upset the nursing sister with my language … I watched the reminder of the battle from the hospital veranda. We were only two or three hundred yards from Ta Kali and there were many near misses.'

On the 31st, Donaldson was flown out of Malta as a stretcher case, but his aircraft, a Liberator, subsequently crashed into the sea on taking-off from Gibraltar; he was one of just three survivors, emerging from the wreckage with burns to one of his arms.

He was awarded an immediate D.S.O., in addition to a Bar to his D.F.C., the latter for his gallant leadership in operations over Sicily.

Subsequent wartime career

After a lengthy period of recuperation, which lasted until March 1943, Donaldson was posted to command R.A.F. Ibsley. And on his promotion to Group Captain in December 1943, he assumed command of R.A.F. Coltishall in Norfolk.

It was in this period that he became heavily involved in organising operations against V2 rocket sites, his knowledge from attacking targets in Sicily proving vital in training his Spitfire pilots to carry out power-dives and precision bombing; originally launched from the U.K., said operations were later carried out from airfields in Belgium and elsewhere.

His final tour of duty was in the Far East from June 1945, where he took command of a fighter wing near Rangoon, but he was evacuated home with malaria after four months.

Post-war

After six months at the R.A.F. Staff College in Bracknell in 1946, Donaldson served on the Air Staff at Leighton Buzzard until June 1948. From there he went on to Leconfield until the end of August 1950, when he became Station Commander at Biggin Hill.

Having then served as Station Commander at Waterbeach until January 1954, he acted as S.A.S.O. at H.Q. 2 Group, 2nd T.A.F. in Germany. His final appointment was as Deputy Director of Air Defence at the Air Ministry and he was placed on the Retired List in 1959.

In later life the Group Captain managed a village shop and sub-post office in Melbury Osmond, near Dorchester. He died on 5 October 1980.

Sold with the following original documentation and artefacts:

(i)

R.A.F. Pilot's Flying Log Book (Form 414), covering the period April 1934 to November 1936.

(ii)

R.A.F. Pilot's Flying Log Book (Form 414), covering the period December 1936 to December 1937.

(iii)

R.A.F. Pilot's Flying Log Book (Form 414), covering the period January 1938 to August 1942, followed by statement: 'Owing to loss of Log Book a detailed account of flying in Malta cannot be given. Below are given a few more of the important dates'; a resume of Donaldson's operational tour in Malta, 27 August to 15 October 1942 follows, together with related press cuttings.

(iv)

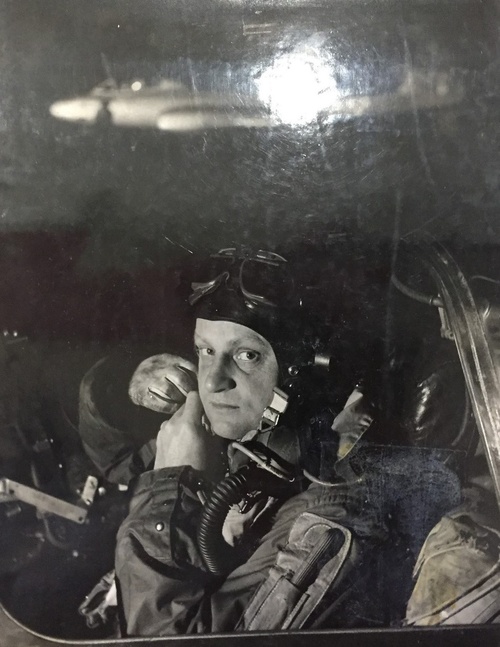

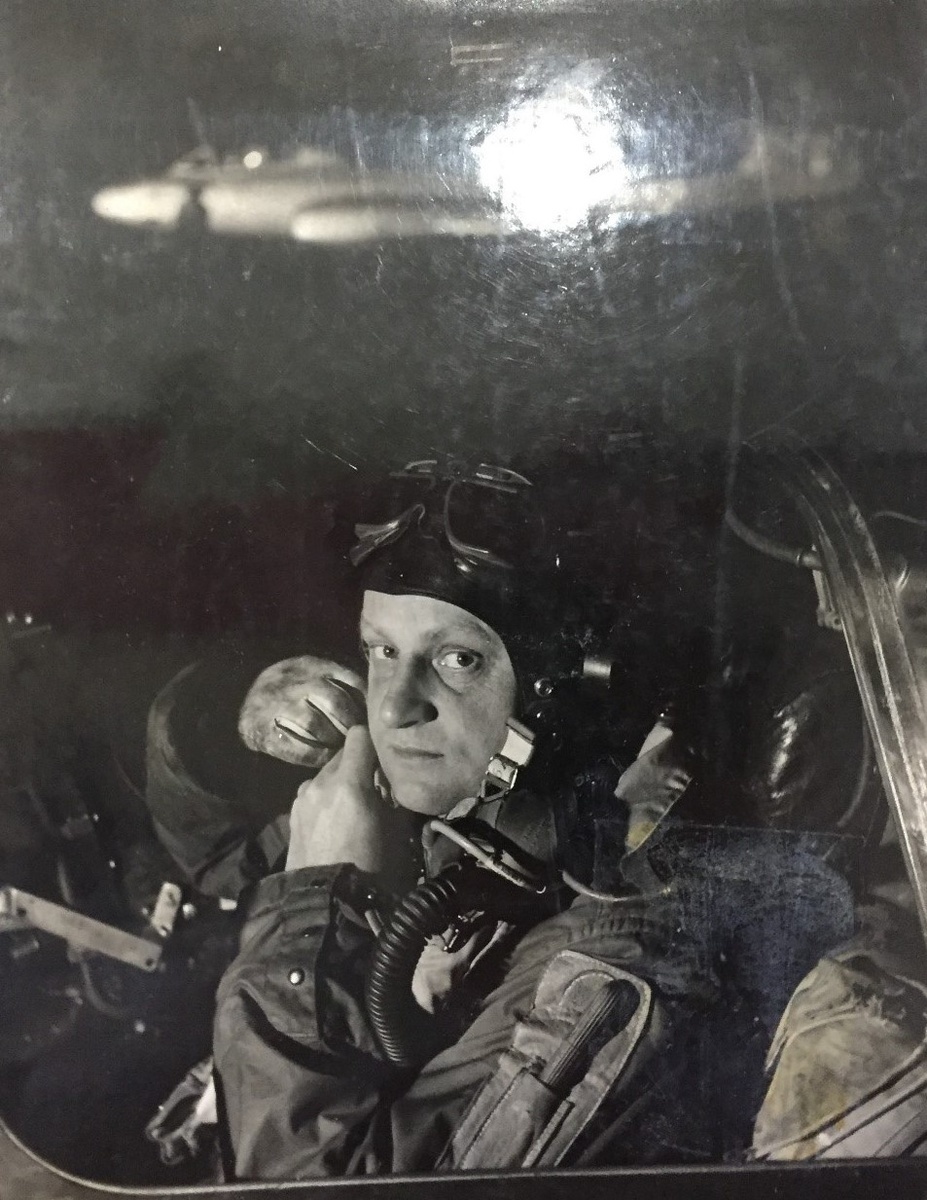

A further R.A.F. Flying Log Book, as used by the recipient as a scrap book, the extensive career content including a mass of newspaper and magazine reports, together with original correspondence, including Buckingham Palace investiture letters, dated 11 November 1941 and 16 September 1943, numerous congratulatory letters from such senior officers as 'Boom' Trenchard, Keith Park and Basil Embry, invitations, Czech Flying Badge certificate, a wartime pencil portrait of the recipient, dated 1942, 'Permit to Enter Fighter Ops Malta' and several photographs; together with 3 records which with recordings of Winston Churchill's speech when he visited Biggin Hill, when Donaldson was Station Commander.

(v)

A copied typescript of the recipient's autobiography, Finger Trouble, 198pp.

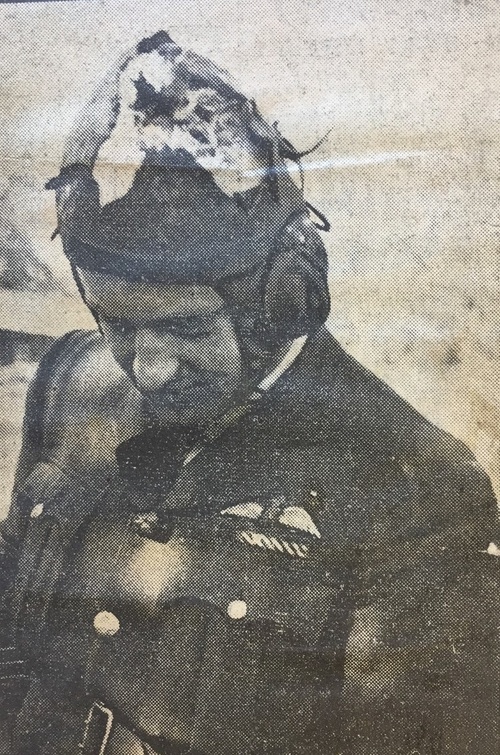

(vi)

The recipient's damaged B-type flying helmet, as worn on the occasion his aircraft took multiple hits from ground fire over Morlaix in 1941; one report states his fuselage was holed in 100 places and his tail wheel shot off.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£15,000

Starting price

£13000