Auction: 20002 - Orders, Decorations, Medals & Space Exploration

Lot: 538

Sold by Order of a Direct Descendant

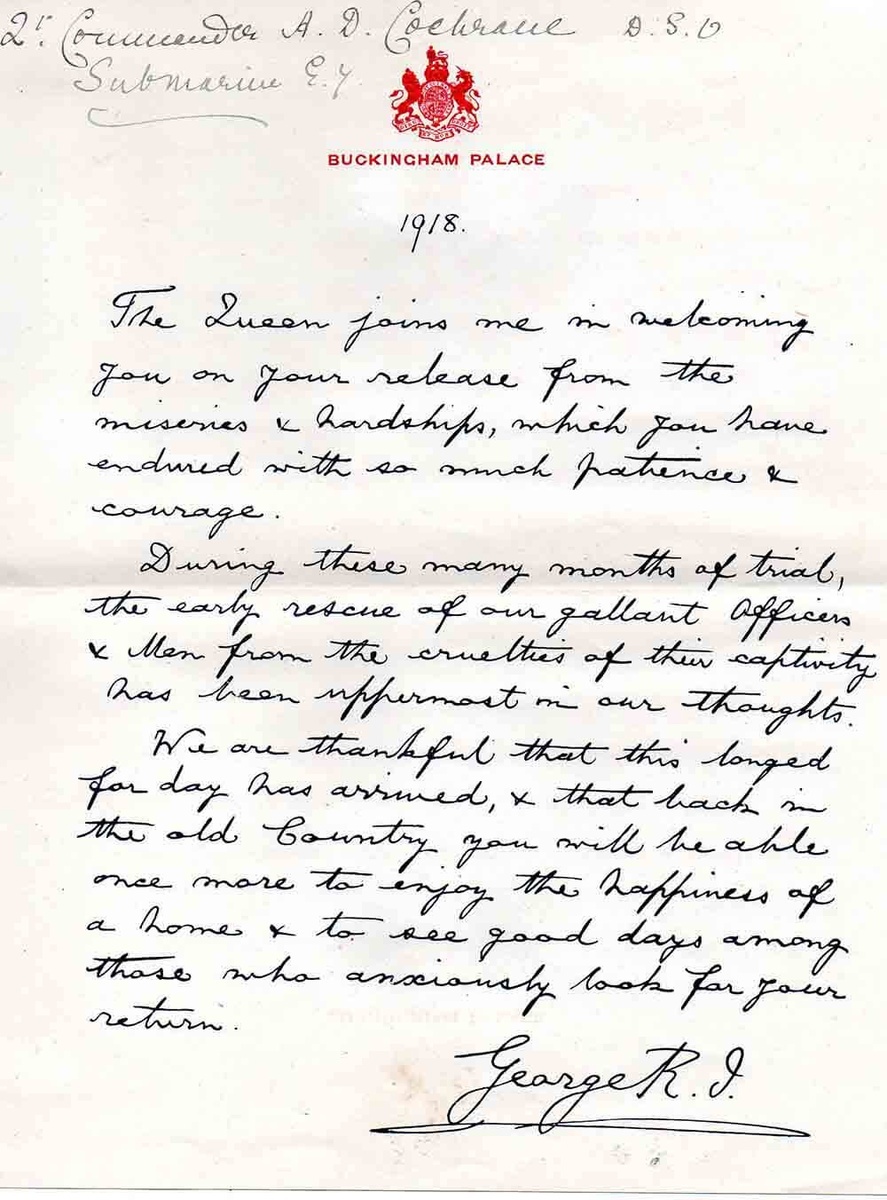

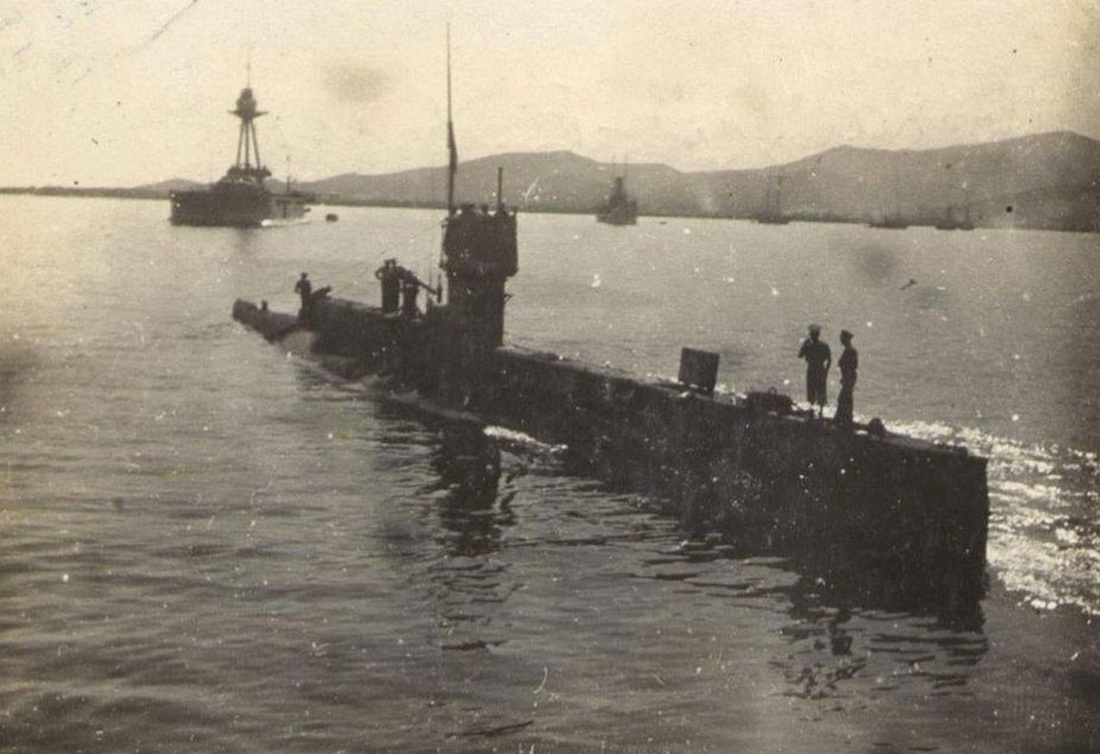

The historically important 'Sea of Marmora 1915 - Submarine Commander's' D.S.O. and 'Yozgad Escaper's' Second Award Bar group of nine awarded to Captain Sir A. D. Cochrane, G.C.M.G., K.C.S.I., K.St.J., Royal Navy, who wrought havoc in E7 - racking up a highly impressive score of enemy vessels and a D.S.O. - before being caught in nets at Nagara and forced to the surface; a U-Boat Captain witnessed the churning waters, rowed out from the shore with a handful of bombs, and calmly dropped them over the side to good effect

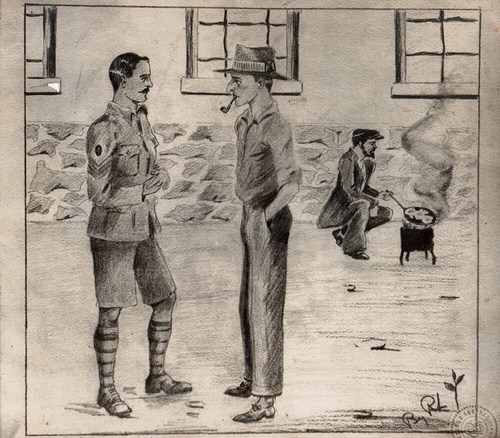

Unimpressed with incarceration, Cochrane and a group of fellow officers determined to escape from the heart of Turkey, making one of the most daring breaks in history, repeatedly putting themselves at the mercy of extreme weather, mountainous terrain and hostile locals - their journey was immortalised in Four-Fifty Miles to Freedom

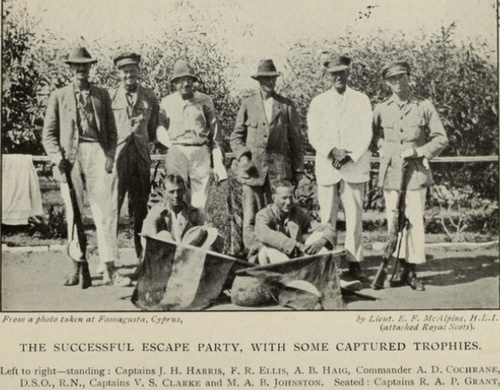

Starved, exhausted and sunburnt to a crisp, his band of brothers made one final attempt for freedom, finally reaching Cyprus; Cochrane duly added a Bar to his decorations although three fellow Sub CO's with similar scores had previously earned the Victoria Cross

Cochrane later forged a highly successful career as a Unionist politician and was latterly Governor of Burma

Distinguished Service Order, G.V.R., with Second Award Bar; 1914-15 Star (Lt. Commr. A. D. Cockrane. D.S.O., R.N.); British War and Victory Medals, with M.I.D. oakleaves (Lt. Commr. A. D. Cochrane. R.N.); 1939-45 Star; Atlantic Star; War Medal 1939-45; Coronation 1937; United States of Merit, Legion of Merit, note surname spelling, good very fine (9)

[G.C.M.G.] London Gazette 1937:

'On the occasion of the separation of Burma from the Indian Empire.'

[K.C.S.I.] London Gazette 24 March 1936.

[K. St. J.] London Gazette 20 December 1937.

D.S.O. London Gazette 13 September 1915:

'For services in a submarine in the Sea of Marmora, where he did great damage to enemy shipping, and after blocking the railway line near Kava Burnu by bombarding it from the sea, shelled a troop train and blew up three ammunition cars attached to it.'

Bar to D.S.O. London Gazette 11 November 1919:

'In recognition of the determination, spirit and resource displayed by him on the occasion of a successful attempt to escape from the prison camp at Yozgad, August, 1918.'

Archibald Douglas Cochrane was born on 8 January 1885 at Springfield, Fife, the second son of Colonel The Honourable Thomas Cochrane, 11th Earl of Dundonald, Member of Parliament for North Ayrshire from 1892-1910 and Commanding Officer of the 2/7th Battalion, Black Watch, and Lady Gertrude Cochrane, daughter of the sixth Earl of Glasgow, of Crawford Priory, Fife, Scotland. Borne of 'Fighting Stock' with a strong naval tradition, Cochrane was also the great-grandson of Admiral Thomas Cochrane, one of the most daring and successful naval Captains of the Napoleonic Wars, nicknamed Le Loup des Mers ('The Sea Wolf') by the Emperor himself and whose life became the inspiration behind C. S. Forester's Horatio Hornblower and Patrick O'Brian's Jack Aubrey. Appointed Knight of the Order of the Bath by Queen Victoria on 22 May 1847 and Admiral of the Red on 8 December 1857, the Admiral ensured that his family name was known across the globe, no less so than in Chile which has named five ships Cochrane or Almirante Cochrane in his honour between 1879 and the present day, including a dreadnought battleship laid down at Newcastle by Armstrong Whitworth in 1913, later converted as the carrier H.M.S. Eagle.

Inspired by his ancestor, Archibald Cochrane entered Britannia at Dartmouth on 15 September 1899, ranking 18th among 62 successful Cadets with 2374 marks. His leaving report noted that he should get on in the service if he worked hard enough. Appointed Midshipman aboard the Majestic-class battleship Mars on 31 March 1901, Cochrane soon tired of life above the waves and volunteered for service in submarines. Much as his ancestor had embraced new technologies, in particular his proposals in 1812 to attack the French coast using a combination of bombardment ships, explosion ships and 'stink vessels' (gas warfare), Archibald Cochrane saw great potential in the embryonic submarine service and was keen to set about learning how the various submersible components worked (Destination Dardanelles, refers).

At this time there was little in the way of formal instruction for young officers, indeed Cochrane and his contemporaries learned at sea by observation of their Captains. Appointed Sub-Lieutenant on 30 April 1904 and Lieutenant on 30 July 1906, Cochrane briefly exchanged his white submarine sweater for the more dignified frock coat, cocked hat and sword whilst aboard Defence in 1910, but returned to submarines in 1912 when placed in command of the D1. Raised to Lieutenant-Commander on 30 July 1914, he spent many valuable months in the lead-up to hostilities patiently keeping her seaworthy, nursing her somewhat unreliable diesel engines and training her complement of 25 from the historic blockhouse of Dolphin at Gosport. The classic images of the dangers of submarine warfare held today have come from films such as "Das Boot" with men huddled quietly together attempting to ride out depth-charge attacks. To Cochrane and other submarine Commanders in 1914, a greater threat lay in human error, technical failure and foul air. In such early days the self-reliance and training of the crew was pivotal and the difference between life and death; when things went wrong, submariners needed not think twice to prioritise self-escape over external assistance.

It wasn't over by Christmas

Operating from Dover and then Harwich, Cochrane spent the latter part of 1914 leading D1 on patrols of the English Channel and off the River Ems in north-western Germany:

'Working close inshore and with great daring, he found the channels constantly occupied by destroyers and trawlers, though, perhaps because of [Max] Horton's success against the S116, they did not seem particularly aggressive. For this patrol in particular he won Keyes's approbation and was subsequently Mentioned in Despatches' (Destination Dardanelles, refers).

At the end of October 1914, Cochrane was moved firstly from the D1 to the D7, and then, just three weeks later, to take command of the E7, Brownlow Villiers Layard taking over from him and leaving the C32 to do so. A fellow graduate from the Britannia intake of September 1899 who ranked 51st out of 62, Layard did not mince his words about Cochrane:

'I was rather frightened of Cochrane. In the Defence I never quite knew how to take him as he is very reserved at times. I know he is a mighty good skipper.'

With Cochrane in command the E7 returned almost immediately to Harwich where it was joined by Sub-Lieutenant Ian Twyman who was hand-picked as Third Officer by the new Skipper from the D1. In a discussion between Twyman and the Second Officer, Lieutenant Oswald Ernest Hallifax, it soon became clear that, despite his eccentricities, the E7 was in safe hands:

'He (Twyman) says that Cochrane is a weird fellow to serve with as he seldom says much, but that he would not leave him for anything. He added that he was as cool as a cucumber and the tighter the fix he gets into the cooler he gets. I am glad to start a new volume of the diary with my first day at sea with Cochrane and feel like burning the rest and forgetting that part of the war. The future will be very different' (The Private Papers of Captain O. E. Hallifax, D.S.O., R.N., July 1914-July 1915, Imperial War Museum, refers).

'A filthy night, raining hard and as dark as sin!'

'Shoving off' at 3.10 pm on 15 December 1914, the E7 departed Harwich with the E2 and began to make its way to Terschelling via the North Hinder Route in an attempt to thwart enemy bombardment of the east coast. The weather was appalling, Hallifax noting in his diary two days later:

'In the winter you get chilled to the marrow and the cold wind nearly blinds you. By the end of my watch my eyes felt like red hot coals'.

Returned to Harwich, the E7 took to sea once again and within days participated in the raid on the Zeppelin sheds near Cuxhaven. Surfacing on Christmas morning 1914, E7 spent much of the day in a game of cat and mouse off the Elbe with a Zeppelin:

'We hoped to hear the anchor cables of the High Seas Fleet rattling down all round us.'

It was not to be. Instead, the crew of E7 spent 20 hours and 51 minutes submerged on the seabed, rising to the surface amid thick fog and in total silence. Settling down to a Christmas dinner of soup, rabbit pie and plum pudding, the crew delighted in the music of a gramophone and the promise of better days to come. On 25 January 1915, Cochrane and E7 surfaced at night between Heligoland and the Weser in wait for the German Fleet following the Battle of Dogger Bank. With Hallifax on watch and standing in solitary grandeur waiting for the enemy, the men aboard E7 waited patiently, all tubes ready, for the chance of the High Seas Fleet to come into range. Again however, they were thwarted. Arriving late, only the E8 to the north-west of Heligoland saw anything of the enemy and was able to fire at a destroyer flotilla. The 'fish', set to run at a depth of only six feet must have been sighted, for the destroyers scattered like a flock of partridges and disappeared from sight at high speed. With their teeth chattering, the crew of E7 gladly switched on the engines and returned to Harwich.

Transferred to Ipswich, the crew of the E7 were inspected by King George V at 11am on 25 March 1915. Parading on the quayside in freezing conditions the crew attempted to cheer the King, their enthusiasm stifled by a piercing northerly wind and woeful number 5's. In his monkey jacket and greatcoat, Hallifax and his fellow officers had a good deal of sympathy for their men:

'Poor chaps they were nearly frozen!'

Returning to patrols in the Bight, Cochrane had a number of close-calls with the enemy but was not able to set sights on a target during these patrols. He did however begin to devise tactics whereupon three or more submarines could give each other mutual support with their guns against aerial attack. These would be mirrored nearly thirty years later with German U-Boats seeking mutual protection from Allied aircraft; by late 1942 boats were setting out from the Biscayan bases armed to the teeth with a 37mm and eight 20mm guns in two quadruple mounts abaft the conning tower and with as many as four boats departing together.

Dardanelles - new beginnings

On 28 May 1915, Cochrane was sent for by the Admiralty and ordered to proceed at once for 'instant deployment' to the Dardanelles. By this time the Gallipoli Campaign was in full swing and, despite the inherent dangers, his crew were keen to get under way. As the crews of the E7 and E12 rushed to embark all the stores, fuel and kit required, Hallifax went to his bunk 'too excited to sleep', no doubt glad to leave the mines, bad weather and boredom of the Heligoland Bight behind him. Arriving at Devonport on 30 May 1915, the two submarines berthed alongside Sarnia and Cochrane used the time to take counsel from Lieutenant-Commander Edward Courtney Boyle of the E14, newly returned from his first patrol in the Sea of Marmora and gazetted for the V.C. seven days previously for succeeding in sinking two Turkish gunboats and a large military transport. It was time well spent; acutely aware of the small number of torpedoes that a submarine could carry on patrol and by the lack of a gun to use on small targets, Cochrane alerted Malta and made sure that his craft was fully prepared for the challenges ahead:

'As the Maltese shoved the bolts in, we hoisted the mounting and the gun into position with great style.'

The weather on passage from Malta was very hot and the crew of E7 were glad to reach their berth alongside Adamant in the natural harbour of Mudros:

'Mudros was an amazing sight. Numerous battleships and other warships were anchored in long lines as if for review. Troop transports and supply ships were unloading new supplies and reinforcements for the army… It was hot, dirty and insanitary. Dead mules floated in the harbour, their long legs sticking forlornly into the air like so many periscopes' (Destination Dardanelles, refers).

Temperatures aboard E7 soon became unbearable with the officers suffering from violent sickness and sunstroke and resorting to sleeping on deck in the evenings. On 10 June 1915, just three days after the safe return of Nasmith from the Sea of Marmora aboard E11, the E14 successfully navigated the Straits for a second time under Boyle. A few days later he was joined by the E12 with Lieutenant-Commander K. Bruce being chosen - much to Cochrane's chagrin - to be the first of the newcomers to attempt the passage. Suffering from defects to both motors the patrol of the E12 was short, but she safely returned to Mudros 'Grouper Down' (slow speeds) on 27 June 1915, entering harbour flying a red flag with a skull and crossbones; this signal of success had first been flown by the E9 when Horton returned to Harwich after sinking the cruiser Hecla, and it later became a universal tradition amongst British and Allied submariners used to this day.

For Cochrane, the news that E12 was returning meant it was time to prepare his crew to take her place and relieve Boyle. Taking the opportunity to fly over the Straits and reconnoitre the topography, he returned to Lemnos and liaised with his officers regarding concerns about the crew:

'The three men with dysentery are joining up again today for I pointed out to the doctor that they would probably recover as soon as we get away from here, for the general opinion is that the flies are the cause of it. Ships in other parts of the harbour do not get infected as much as we do. We think that they come from the slaughterhouse which is just opposite us on the water's edge.'

Despite Hallifax himself suffering from dysentery, the full complement of E7 departed their berth on the Adamant and set course for the Sea of Marmora at 7.30pm on 29 June 1915. As the submarine left harbour a vicious north-westerly squall burst overhead accompanied by brilliant forked lightning all around the horizon. Some might have regarded this as a sign of trouble to come for the Turks.

Sea of Marmora

Making steady progress northwards, Hallifax witnessed the passing of the storm which was enhanced as the gun flashes flickered over the tip of the peninsula and occasional flares shot into the sky. To starboard the searchlight at Kum Kale shed its powerful beam over the waters whilst overhead the crew could hear the express-train roar of a heavy shell on its way towards the British trenches as a Turkish battery on the Asiatic shore fired steadily. Hallifax had little time however to appreciate the scene for hardly had he reached the bridge than Cochrane ordered 'Diving Stations' and the E7 proceeded to slide down gently to 80 feet. What Hallifax did not realise was that Cochrane was ill, probably with wisdom too ill to have gone on, but driven to do so by his own fierce determination:

'Cochrane merely moved the ruler over the chart without any pencil marks, then folded up his chart and sat on it. He took two more fixes in this manner with Twyman kept well away. It was only later he told us that the bearings were shams for he could not see anything clearly! It's this infernal diarrhoea or dysentery!'

Safely through the Straits, Cochrane took E7 to the bottom and waited for darkness. Consulting his charts his watering eyes gazed upon the Sea of Marmora, regarded by many as a box some 150 miles long from east to west and about 40 miles in breadth at its widest point, graced to its northern shore by the city of Constantinople and its twin Scutari, lying aside the Bosphorus. Bordered throughout its length by high mountainous country at first glance it looked like a dangerous place for a small submarine, but with few good roads and fewer railways, deep water and a ready supply of targets, it offered opportunities which he could only have dreamt of months before. Most of the crew went to sleep, few bothered to eat. Inside the air was foul, the batteries low on power and the inside of the hull was dripping with condensation.

Liaising with Boyle on 1 July 1915, Cochrane made course for the port of Rodosto and carefully closed inshore. Spotted by three vessels, the presence of the E7 created panic which caused one to run aground. The other two lay helpless in the shallows, their crews ashore being unable to do anything. Having fired a round from the deck gun which caused consternation ashore, Hallifax was ordered by Cochrane to prepare a scuttling charge and while doing so was told by Cochrane to bring a tin of petrol to the bridge as he did not wish to waste too much time. He would then use the charge on the brigantine after Hallifax and Able Seaman Matthews had set the steamer on fire:

'There were plenty of wicker baskets lying around so we jammed them on the bunks and poured some petrol on each mattress. Not having had anything to do with petrol for so long now I forgot how it vaporises and thought of it as paraffin, and having sent Matthews on deck with the half-empty can I told him when he returned to light his side and then nip on deck, and I would light mine and follow him.'

In a small compartment Matthews lit his match and leant forward:

'There was a blinding flash and the air seemed to burst into flame.'

Both men were seriously injured, Matthews being burnt to the face, neck, forearms and hands. Hallifax had the side of his right forearm burnt raw and both feet and legs up to the calves were raw and blistered. In agony they scrambled to safety from the burning ship, their wounds being soothed by pouring a large case of sperm whale oil over both men.

Meanwhile the steamer was burning merrily and a couple of shells on the waterline hastened her end. Within minutes Cochrane had destroyed three enemy vessels and such was the ferocity of their demise that he repeated the feat of arson the following morning leaving a brigantine burning fiercely. The Greek crew were towed to shore - a kindly act, only interrupted by the rude arrival of a Turkish gunboat. Aboard E7, the condition of both men was causing considerable concern and he resolved to send them back with Boyle in E14 if they should meet again. It was not to be:

'Whilst dived Cochrane examined my feet and legs and they were a horrid sight - covered with huge blisters like Portuguese men-of-war…'

Adding to his woes, Hallifax suffered a recurring bout of dysentery and could manage nothing more than thin soup, biscuits and tea with a few vegetables for lunch. The following day his diary entry noted 'torture when I have to use my feet' and 'swinging along from pipe to pipe and beam to beam with only my heels touching the deck'. Illness soon spread throughout the submarine and conditions became little short of intolerable with Leading Signalman Parodi straining every minute and passing blood.

Success in adversity

Despite such trying conditions, the daily toll of small enemy shipping sunk or damaged by E7 rose steadily. A dhow which had been converted in a similar vein to a 'Q' Ship met a grisly end at the hand of the E7's deck gun and a ferry was chased and run ashore, being sunk in deeper water the following day. Gradually Cochrane and his crew became a thorough nuisance to the Turks, regularly sinking the small craft and ferries which were so essential a part of communications between Constantinople and the forces on the Gallipoli peninsula. On 10 July 1915, Cochrane brought E7 into the Gulf of Mudania and successfully despatched a 3-4,000 ton steamer from 1500 yards - the first successful torpedo attack of the E7. Cochrane later reported that a column of water was thrown about 300 feet into the air and the ship broke in two by the mainmast (Destination Dardanelles, refers).

The E7 withdrew seaward after this attack and, finding a quiet spot where Cochrane hoped they would be out of sight, celebrated by allowing all hands to bathe. It was not just an attempt of recreation but had the serious purpose of allowing the crew to have a decent wash. For Hallifax the experience was bitter sweet:

'I had to wear my green glasses to prevent being blinded in the bright sun after so long in artificial light. I did envy the men washing and bathing.'

Interrupted by a patrolling gunboat, Cochrane remarkably managed to get all his swimmers aboard and dived to safety. His report merely stated 'Gunboat interrupted the proceedings while ventilating and washing clothes'. It somehow failed to mention his own justifiable annoyance for it was his turn to bathe next! Consulting the Naval medical book, Hallifax was feeling similarly aggrieved:

'Our medical book is of no help for it only gives directions for a couple of days' treatment "By which time of course the patient will have medical aid from the parent ship!"

Red letter day

In contrast to their bad luck in failing to sink the old gunboat Muni-i-Zaffer on 13 July 1915, 15 July offered a real tonic to morale as this was the day when they emulated Naismith in E11 and attacked the enemy in Constantinople. From a position where Europe and Asia are only about a mile apart Cochrane fired a torpedo at the Topkhana Arsenal where a large number of small craft lay alongside loading munitions for the front. No one aboard could doubt that they had hit something for a long loud explosion was clearly heard and was greeted by a great cheer. Hallifax noted 'that he looked awfully bucked and can't stop smiling.'

That evening the E7 moved southwards to be in position to bombard the nearby powder mills at Zeitun. With the target silhouetted by the lights of a passing train, E7 rapidly fired twelve rounds. The results of these two actions were perhaps minimal in themselves but they produced a reaction ashore out of all proportion to their worth. Having witnessed their Capital being attacked, many Turks were convinced that the British fleet had at last broken through the Dardanelles and this was but a foretaste of the bombardments to come; many fled to the believed safety of the surrounding countryside leaving munition outputs heavily depleted in the months to come.

Trains become targets

As sailing vessels and steamers became scarcer, Cochrane's attention shifted once again landward, this time towards the railway track which ran close to shore in many places and was well within range. The conduit for nearly all the supplies and reinforcements between Asia Minor to Constantinople, it offered a tempting and somewhat vulnerable target to an opportunist submarine commander. On 22 July 1915, Hallifax noted in his diary:

'We were closing in to shoot at the tunnel when Cochrane saw a train coming along - quite a short one - so we opened fire. They had just got the range, one shot just missed the funnel of the engine, when the train nipped into the tunnel.'

It was not until Hallifax was serving in Australia with the RAN's flotilla of 'J' class submarines in 1919 that he heard more of this incident. This train had not been carrying ammunition, nor even Turkish reinforcements, but rather the surviving crew of the AE2 with their guards. It was just as well that they had not had time to hit the train before it reached the safety of the tunnel, but even so the E7 had been cursed bitterly by their fellow submariners. Blissfully unaware, Cochrane then turned his attention to a stone bridge carrying the railway over a stream. His shells repeatedly struck its sides, but the structure held firm.

Suffering from neuralgia and with dysentery still rife amongst his crew, Cochrane was glad to round Nagara and return to Mudros after twenty-four days in the Sea of Marmora. In their wake was a trail of sunk and burning ships, a patrol in which Cochrane had truly emulated the deeds of his famous ancestor. Altogether it is believed the E7 accounted for one gunboat, five steamers including one of about 3000 tons, and seventeen large sailing vessels, besides any lighters destroyed by the torpedo fired at the arsenal in Constantinople and the damage to the railway by their bombardments. In the words of Hallifax:

'Cochrane was absolutely splendid. The tale of our doings is the sort of thing one reads in the old days… We fairly shook things to the core!'

This was the first recorded occasion on which a submarine had been employed to attack positions on land. Keyes recognised the worth of the patrol and believed that, like Boyle and Nasmith before him, Cochrane had earned a Victoria Cross for his efforts, but, like almost everyone else, did not believe that he would be awarded one. In the event Cochrane received the D.S.O., Twyman the D.S.C., and two ratings the D.S.M.; for Hallifax and Matthews there were still many painful weeks ahead before they would be fit for duty again, but they were relieved to receive proper medical attention at last and to escape the filthy conditions aboard E7.

Return to the Dardanelles

Refitted at Malta, the E7 returned to Mudros on 25 August 1915 and the news that the British were not the only side to send submarine reinforcements to the Mediterranean and Dardanelles. Leaving Bodrum on 13 August 1915, U14 commanded by Von Heimburg discovered a large and unescorted troopship to the east of Duoro Sound. Firing a single torpedo from an ideal position on the beam at 1750 yards, he sent the 11,000 ton Royal Edward to the bottom in a matter of minutes taking with her nearly 900 officers and men. At the same time the U8 was attacking shipping off the landing beaches at Suvla Bay - but was soon to return with damage to her batteries which were giving off chlorine gas. Cochrane was anxious to sail, the E7 now armed to the teeth with bombs - 'lovely little things', and 'chock-a-block with torpedoes and ammunition.'

At 2am on 4 September 1915, Cochrane departed Kephalo Bay and headed once again for the Sea of Marmora, his sights set on inflicting damage in the Golden Horn and possibly acting as a supply vessel for Short 184 seaplanes bent on delivering aircraft-delivered torpedo attacks. In contrast to their first trip the night was very calm and there was a bright moon, so when abeam of Achi Baba, Cochrane dived to avoid being seen from shore and alerting Turkish defences and passed under the minefield. By 6.30am the E7 was off the fort at Kalid Bahr and it was here that things began to go quickly awry.

Caught in the nets at Nagara

Their periscope spotted, the shore defences opened up on E7 and forced Cochrane to dive at full speed on both motors heading towards the net at a depth of 100 feet. All at once there was a terrific jolt as if the boat had run aground. The shock flung men off-balance, while seconds later another shock completed the confusion when the net which had caught them stretched, and then proceeded to fling them astern despite the powers of the motors. Although the bows had in fact forced their way partially through the net, the E7 was firmly held. With the starboard propeller fouled and its engine stopped, Cochrane coolly increased the port motor to full speed for ten minutes and succeeded in freeing the former from its netting. Then, at 8.30am a mine exploded a few hundred feet from the boat - no damage was done.

After about two hours' manoeuvring the boat was turned to the south, and repeated attempts to clear the net were made at depths from 60 to 130 feet by alternatively going at full speed ahead and full speed astern. Although several meshes of the net were carried away it was impossible to gather sufficient way to clear completely the many parts which were holding the boat fore and aft. Realising his predicament Cochrane set about burning confidential paperwork and then determined to lie low and let the hours slip by until darkness. Unbeknown to him, the fully alerted enemy prepared the next move.

At 6.40pm a mine exploded only a few feet from the hull. Its violence broke the electric lights and small fittings and gave Cochrane reason to restart the motors in the hope that the net had been destroyed, but this was not the case. The presence of enemy craft made it impossible to attempt to clear the obstruction from above and so Cochrane made the decision to come at once to the surface and remove the crew from E7 before blowing her up. Up the crew came, one by one, and stepped unhindered into captivity, among them Chief Stoker Asher Coates who was not to survive the Turkish POW camps; Able Seaman 'Johno' Johnson, the boat's mascot, who had already survived the sinking of the Hogue, to be rescued by Cressy, only to be a survivor a second time within an hour when that ship too was sunk; Leading Stoker Wilson who couldn't swim, despite all their efforts to teach him; and Able Seaman Reid, ever the humourist, who like Coates would not survive the rigours of captivity.

Cochrane himself was the last up from below, having opened the vents to the ballast tanks to dive the boat and then fired the fuses to the scuttling charges. Unlike the afternoon spent swimming in the little cove, he was the only one to get wet for as he prepared to jump the submarine began to settle and he had to be dragged aboard the Turkish motor boat. He had hoped that the explosion of the charges as the E7 sank would tear great holes in the net which would not be repaired before the next boat tried to get through the Marmora, however this was thwarted when the main charge failed to detonate; perhaps the inrush of water down the conning tower displaced some of the fuses. In any event, E7 went to the bottom, leaving the net largely in place.

The architect of the final explosion which ended any hope for the E7 was none other than Von Heimburg of the U14 who had arrived at Chanak from Bodrum that very day. Learning of the drama taking place only a few miles away he arranged for explosive charges to be removed from his vessel and proceeded to row to the scene where they were promptly dropped over the side. His actions thereby ended Cochrane's plans which even today remain a mystery:

'Whatever he planned for the seaplane, it is unlikely that he would have been content for the E7 to play the passive role of a submersible garage. Perhaps he planned a combined attack in conjunction with the seaplane of Constantinople where the Goeben and Breslau lay near the Golden Horn.'

With the final withdrawal of troops from the tip of the peninsula at Cape Helles on the night of 8-9 January 1916, there was now no need for further attempts on the Dardanelles by the submariners. Cochrane and his crew in the meantime were taken to Constantinople and locked up in the local prison along with common criminals. Eventually they were sent to POW camps, Cochrane going to Kara Hissar, situated in the middle of Asia Minor about 130 miles from the nearest coast with wild country intervening.

Striking out

In March 1916, Cochrane with Lieutenant Price and Lieutenant-Commander Stoker - who had commanded the AE2 - escaped from camp. The trio travelled through the Taurus Mountains towards the coast but after eighteen days their strength was nearly gone, they were starving and their boots lay in tatters. Within sight of the sea they resorted to asking for help at a goat herder's hut and despite their pathetic condition attempted to pass themselves off as German surveyors! Betrayed and captured, they were taken to Constantinople and held for six months in solitary confinement before being brought before a Court Martial. Extraordinarily, they were then sentenced to twenty-five days imprisonment.

Bar to D.S.O.

Eventually in April 1918 Cochrane arrived at camp in Yozgad, situated deep in the Anatolian Mountains some 4500 feet above sea level in some of the most rugged and forbidding terrain in all of Turkey. Rather than rest on his laurels and submit to daily life as a P.O.W., Cochrane joined a remarkable group of twenty-six prisoners determined to escape. On the night of 7-8 August 1918 they began one of the most brilliant break-outs of the entire Great War, Cochrane leading the fourth and largest group in one final bid for freedom. The tale is beautifully described in the publication Four-Fifty Miles to Freedom: The Adventures of Eight British Officers in their Escape from the Turks, written by Captain M. A. B. Johnson, R.G.A., and Captain K. D. Yearsley, R.E., both travel companions of Cochrane.

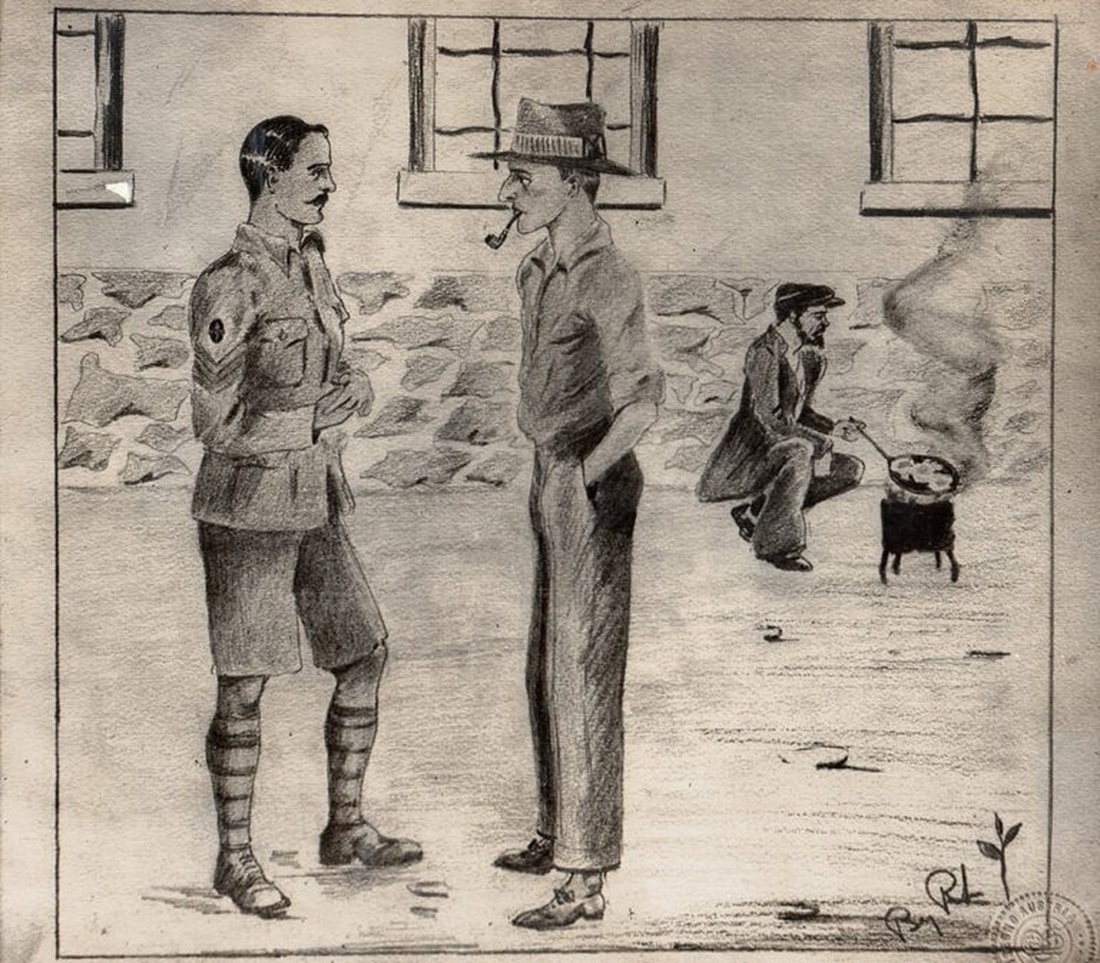

The Escape

Cutting the bars of a window of the Hospital House - part of Yozgad Camp - with the aid of a steel saw, Cochrane and his friends descended down a rope-ladder to the ground at 9.15pm and began to inch their way through gardens, across crumbling stone walls and along dry river beds, before scrambling up the northern side of "Hades" to a vast plateau around midnight. Travelling by night and sleeping during the heat of the day, the going was slow and fraught with danger, not least their regular sightings by local herdsmen who were keen to relieve the little party of coinage and much else besides.

The Turkish authorities were very much concerned about the escape and determined to watch all roads and pathways leading to the coast, so the going remained desperately slow with the men sleeping in ravines, caves and scrubby bush, all the while considering how to access fresh water which was soon leaving their canteens redundant. After a week thirst began to control their movements and they found themselves regularly calling at isolated farmhouses in the search of something to drink and eat; in some places the local people welcomed them and offered sour milk and bread, whilst in others the greeting was less than friendly, the party forced to hand over their watches in return for basic sustenance and the hope that their presence would not be given away.

By 19 August 1918 the little party had reached the Hasan Dagh peak and an hour later discovered a few reed huts and a vegetable patch festooned with watermelons. Liberating the fruits, Cochrane was met by a 'villainous-looking cutthroat' no doubt embittered at losing much of his crop - pretending to be German surveyors, the party were fortunate to escape, the Turk even offering advice as to the location of a stream:

'The paddle was refreshing to the feet; the water for drinking purposes less encouraging, for above us the cattle were watering and the bottom was muddy.'

A few days later on their third week of liberty the men greeted the Taurus Mountains as the heat-haze lifted. By this time tempers were frayed and Cochrane had the thankless task of trying to keep the balance between those who demanded water on or off the nearest route and those who howled for smooth-going for the sake of their agonised feet. By this stage their food reserves had been eaten, the terrain offered almost no opportunity for liberation of foodstuffs, unguarded sheep were in short supply and the prospect of tortoise for a third night in a row had many looking to the stars for their next meal. It was then that luck dealt the men a lifeline when a sudden rainstorm enabled all to fill their water bottles undisturbed. In so by doing, they were able to brew tea and cook rice with a garnish of oxo - of which they had almost a superfluity owing to the number of days on which they were unable to cook.

In the heart of the Taurus

By 25 August 1918 the party crossed the watershed of the Taurus and settled in position a little to the west of a range known locally as Gueuk Tepe. After evading a group of bandits who fired over their heads, Cochrane and his party made one final attempt for the coast which was only 50 kilometres away, this time by day - valuing speed over concealment. On a diet of yourt, boulgar (porridge made from crushed wheat) and stinging nettles, they finally made their way down isolated valleys to the sparking azure waters of the Mediterranean. Following the coastal road to Selefke, Cochrane and his party concocted a story that they were German archaeologists and began to search in earnest for a boat which they could get hold of at night or perhaps a crew who might be able to land them at Cyprus - with the promise of much money for their troubles:

'In the early evening, Nobby, Looney, and Johnny went off to reconnoitre, but it was impossible to approach the coast by daylight because of the men moving about… Two years before, Lord Roseberry's yacht, the Zaida had been mined a few miles along the coast at a place called Ayasch Bay, which she had entered for the purpose of landing spies' (Four-Fifty Miles to Freedom, refers).

Clearly escape was not going to be all that simple, made harder by the presence of Turkish sentries and coastal batteries. Having conducted an inventory of supplies, it became clear however that the men could not waste time in discovering and obtaining a motor-tug or other boat. They were starving, dehydrated and utterly exhausted, but they could not wait another precious hour. Upon the return of the first group it was clear that a second had to go back into the scrubland wilds and find salvation. It fell to Cochrane to lead, but he was physically spent:

'Cochrane, indeed, had undertaken what proved beyond his powers; upon him more than any had fallen the brunt of the work in guiding the little column after night and day after day. It was not to be wondered that on this occasion he had proceeded a mile before his legs simply gave way beneath him, and he had to allow Nobby to proceed alone' (ibid).

The second reconnaissance proved fruitless and the men resigned themselves to life in a ravine:

'From now onwards, for the rest of our stay on the coast, we settled down to a new kind of existence - in fact we may be said to have existed, and nothing more. Life became a dreary grind. None of us wanted to lie a day longer than absolutely necessary in that awful ravine, but we were at present simply too weak to help ourselves. To carry out a search for another boat was beyond the powers of any one' (ibid).

The ensuing blisters of their travels did not last long, for within twenty four hours the flies had eaten them all away. It was not many days before hands which had been scratched by thorns became covered with septic sores and some of the party took to smoking cigarettes made from the dried leaves which littered the stony streambed of their unhappy home. Nor at night was it possible to obtain peace. The flies had no sooner gone to their well-earned rest than the mosquitoes took up the call with their high-pitched trumpet notes. But it was not the noise of course which mattered; at night Cochrane and his men resorted to sleeping with pieces of cloth or handkerchief's over their faces and pairs of socks over their hands.

Living on brews of boulgar, locust beans and flour scrounged or liberated from the local mill, the group finally decided that it was within their powers to make another reconnaissance on 6 September 1918. Cochrane and Nobby set off once again down the ravine at 5pm and soon came across a party of four Turks oblivious to their presence:

'At this juncture Cochrane swallowed a mosquito. Nobby says that to see him trying not to choke or cough would have been laughable at any less anxious time' (ibid).

In view of the number of Turks about it was clearly no good increasing the risk of detection by having two persons on the move; so, soon after, Cochrane left his friend in a place of concealment and went scouting by himself. He was in luck - there were two boats in the little bay below, one a 28 foot cutter - and they appeared largely unguarded. Having seen all he could hope for, Cochrane lost no time in moving off and returning with Nobby to the rest of his men in the ravine.

All or nothing

The news of a boat brought the beleaguered men hope and something definite to work for. Setting the night of escape as 8-9 September, they set about fashioning paddle heads from flat pieces of board and utilised a piece of ancient, baked pottery - which served as a whetstone for their blunt knives. Breaking into their final reserve of tobacco, Cochrane then sent two men to a deserted village armed with a long list of requisites:

'More cloth for sails; a big Dixie for cooking large quantities of the reserve porridge at a time; some more grain (to be liberated from the local mill); nails and any wood likely to be of use; cotton wool for padding our feet when we went down to shore; and many other things' (ibid).

The exercise proved a great success, the men also returning with raw coffee beans which were roasted and ground the next day - and turned into 'the two finest drinks of coffee we remember having had in our lives'. Utilising rolls of cloth taken from the village, the men fashioned three sails but were not ready to take their one and only chance on the night in question; their chief fear remained the shortage of drinking water.

The following evening Cochrane led his men to the water and they made their move. With a sleepy Turkish sentry coughing in amongst the scrub, Cochrane and Johnny swam to a little boat and began to heave themselves aboard, aware that every splash could give away their presence:

'They had hoped to find it anchored by a rope, but to their great disappointment it was moored with a heavy iron chain. Speaking in very low whispers, they decided that one should go under the water and lift the anchor, while the other, with his piece of rope, tied one of the flukes to a link high up in the chain… Accordingly Cochrane dived and lifted the anchor…' (ibid)

Despite spending a vast period of time in the water, it became clear that the anchor and chain were too heavy for just two men to lift. As Cochrane shivered naked in the water, he soon realised that further attempts would only create further excessive noise and wake the sentry from his slumber. He returned to his men and in turn they weaved their way back up the gully; the attempt had failed.

As the dusk of their 36th night on the run fell, a ration of chupatties and a couple of handfuls of raisins were issued. Holding a council of war, the men knew their time was all but up, yet they determined to make one last break for it before either the weather, starvation, dehydration, illness or simple discovery ended their adventure. Setting forth that night, their simple plan was to either seize a boat in the bay or bluff their way to a nearest harbour - pretending to be Germans - and concoct whatever story was necessary to get their feet aboard a vessel capable of travelling to Cyprus.

Setting forth on their last great venture, Cochrane set foot back into the Mediterranean waters and determined to follow a new course up a small creek. This time he managed to find a dinghy belonging to a lighter and used his newly-sharpened knife to cut it free. Gathering his friends from the same bay as before, the men quietly paddled to the lighter and began to untie a motorboat which lay alongside under the light of a small hurricane-lamp. With frantic but failing efforts to turn over the engine, Cochrane took matters into his own hands and rigged up the mainsail fashioned days before; all then clambered aboard from the dinghy and gradually the men moved off.

The engine started with a roar

Down below, Cochrane began to experiment with the magneto in the cramped space of the engine-room. At length at 4.30am, little more than an hour before dawn, the engine started with a roar, in went the clutch, and off went the motor-boat 'at a good seven knots'. Nobby, who was feeling very much the worse for his exertions in weighing anchor was suddenly startled by a series of explosions:

'He thought for a moment that a machine-gun had opened fire at short range, till he discovered that he was lying on the exhaust-pipe, the end of which led up on deck!

Cyprus and Freedom

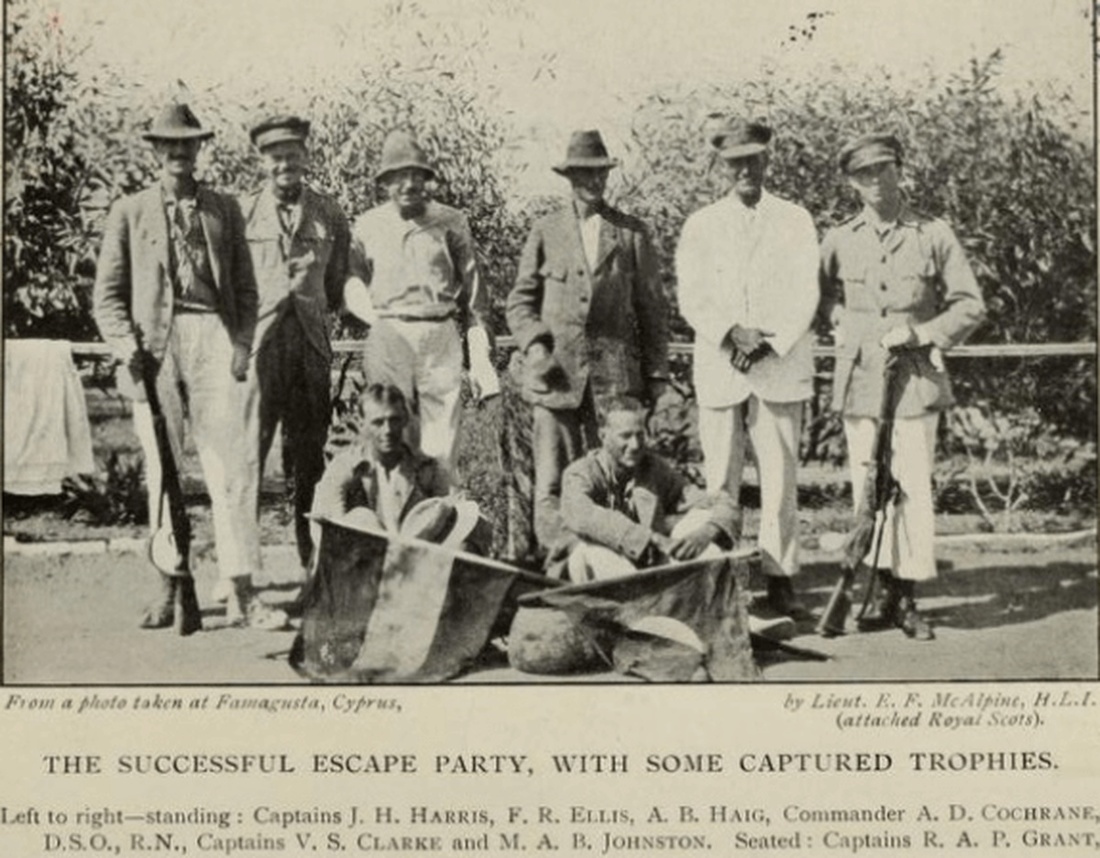

Arriving at Cyprus by sail and motor, the men were all too dazed and exhausted to realise for the moment what it meant. Cochrane, with his keen sense of small, had declared that there were cows not far off, and at about 3 o'clock the men heard a cock crow. That bird would be breakfast without question. As the stars disappeared and the men witnessed the coming light of dawn, they finally made landfall and were greeted by a crowd of Cypriotes who brought cigarettes and directed Cochrane to a nearby jetty:

'Here we stepped on British soil, eight thin and weary ragamuffins. We know our hearts gave thanks to God, though our minds could not grasp that we were really free' (ibid).

Half an hour later the party were taken to the barracks of the Cyprus Mounted Police where they were given coffee with sugar in it:

'A Greek doctor anointed us with disinfectant and bandaged anything we had in the way of sores or cuts' (ibid).

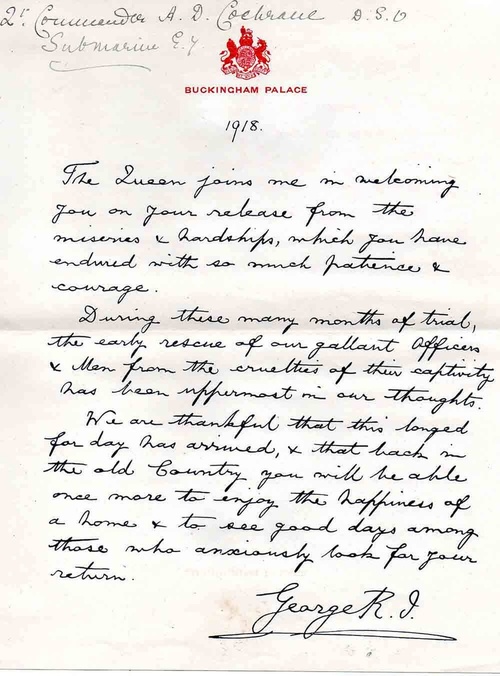

Sent to Kyrenia and on to Famagusta, Cochrane spent four exceedingly pleasant days in Cyprus before finally travelling home via Egypt, Italy and France, arriving around 16 October 1918. Received by His Majesty the King, each of the party received a kindly welcome and sympathetic interest, Cochrane being later decorated with a Bar to his D.S.O. for his remarkable leadership and spirit displayed over 36 days in enemy-held territory. He was also 'mentioned' (London Gazette 17 January 1919, refers). Whilst many later regaled that 'divine intervention had brought them through', those who were actually there knew their salvation lay in the leadership, ingenuity, passion, and above all, the determination of Cochrane.

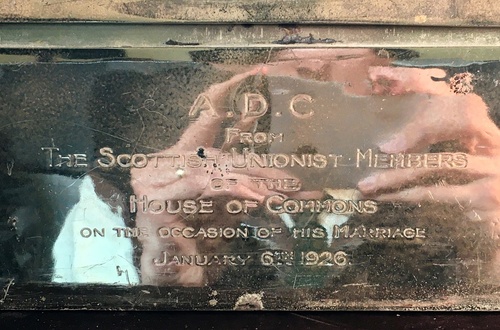

Post-War

Returning home to Scotland, Cochrane was appointed as Unionist Member of Parliament for East Fife on 29 October 1924, succeeding the popular barrister and Liberal politician Sir James Duncan Miller. In January 1926 he married Julia Dorothy Cornwallis at St. Nicholas' Church, Linton, near Maidstone. Officiated by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Randall Thomas Davidson, the wedding was on such a scale that five hundred Boy Scouts and Girl Guides formed a guard of honour outside the church (The Essex Chronicle, 15 January 1926, refers).

Cochrane subsequently lost his seat at the 1929 General Election, but took the opportunity to contest the 1932 Dunbarton by-election following the resignation of Lieutenant-Colonel Sir John Gibb Thorn. He returned to Parliament on 17 March 1932 and served his constituents for four years before succeeding Sir Hugh Stephenson as Governor of Burma in 1936.

A day at the races

With such a plethora of information regarding the military and public life of Cochrane, we have chosen to consult the writings of his son Douglas Fiennes Cochrane to truly appreciate the man:

'Cousins who are alive and knew him recall him well when they can be less complimentary of other family members. My godfather as a young boy was scared by his formal manner. Another cousin remembers him as more fun, as a boy using my grandfather as a climbing post. Memories are unreliable of course but from the fragments a picture emerges of a man who was still but fair and always gave credit to the men who served with him. At times he may have been easier to respect than like, yet he stayed in touch with his fellow escapees, helping them in later life. As a man with some influence he worked to secure pensions and financial arrangements for his fellow sailors and the relatives of dead seamen. His letters from Burma to my grandmother are surprisingly tender.'

His time in Burma falls at an interesting period in time, with poet Pablo Neruda suggesting the British were 'monotonous and even ignorant'. Neruda was himself ostracised for fraternising with the local people and developing a love for Burmese culture and society. It is thus perhaps pertinent to note that Neruda and Cochrane became good friends, the latter - being a dour Scot - happily turning his back on English sensibilities and instead sharing a genuine love for Burma and its peoples.

Cochrane resigned the position of Governor of Burma in 1941 having assisted with the introduction of a new constitution which aimed to confer greater democratic freedoms upon the people of Burma. His character was noted thus:

'The Governor, Sir Archibald Cochrane, D.S.O., a former naval officer, felt a little at sea in Burma's politics or perhaps it should be said, noting his former regular profession, a little on dry land, but he did a thorough and honest job in his term of office' (Burma's Constitution, Maung Maung, refers).

He returned for service in the Second World War, being appointed to the command of H.M.S. Queen of Bermuda, taking her on a 'pamphlet convoy' from Suez-Sydney and being retired in the rank of Captain on 3 September 1945. Cochrane later took employment as a director of Standard Life and set about raising a son and a daughter. He died on 16 April 1958 at Inglisfield, East Lothian, and was buried at Cults Kirk Cemetery, Fife, Scotland, near the ruins of Crawford Priory where he spent much of his time.

Note:

Regarding the awards of the other Sea of Marmora CO's, Naismith's V.C. is dispayed inside the main doors of the Britannia Royal Naval College, Dartmouth; Holbrook's V.C. was donated by his widow to the town of Holbrook, Australia and is now on display at the Canberra War Memorial; Boyle's V.C. is in the Royal Navy Submarine Museum, Gosport, Hampshire.

Sold together with the following original documentation;

(i)

A handwritten account of the patrol of E7, recording such events:

'We returned safely yesterday after 24 days up the Dardanelles in the Sea of Marmora...you can take it from me that it was a fine show. We broke all previous records. Cochrane was absolutely splendid. The tale of our doings is the sort of thing one reads about in old days...We fairly shook things to the core. We are the first submarine in history to bombard a place on shore under fire.'

(ii)

Letter from Cochrane at H.M.S. Lucia, Submarine Depot, dated 1 December 1918:

'Dear Robertson,

Many thanks for your letter of Nov 28th, by the same post I heard that one of the three escapees about whom I was no anxious had arrived in Egypt, so that even if they did reach Cape Arora the affair is no longer a tragedy & I am much relieved.

I will certainly let you have an account of our trip; it is not ready yet but two of the party have undertaken the job.'

(iii)

London Gazette, 23 October 1914, with forwarding Admiralty letter to Cochrane's father, dated 25 January 1918.

(iv)

Letter from the Grand Priory of St John related to the award of the Order to Lady Cochrane, dated 29 April 1938.

(v)

Order of St Michael & St George, Annual Service booklet, 1948.

(vi)

Letter of confirmation of award, Apporval to Wear and Foreign Office forwarding letter related to the award of the Peruvian Order, 1957.

(vii)

A large and impressive silver presentation box, hallmarks for Birmingham 1911, the front engraved 'A.D.C. from the Scottish Unionist Members of the House of Commons on the occasion of his marriage January 6th 1926.'

(viii)

His binoculars, in their fitted leather case.

(ix)

A number of further photographs, newspaper cuttings and letters, besides family DVD with footage.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£12,000

Starting price

£12000