Auction: 20002 - Orders, Decorations, Medals & Space Exploration

Lot: 384

'The last few times I was up we ran into about 200-700 huns.

The last time there were 700 of them [5 November] and I was shot down.

The nearest bullets went through the cockpit 2.5 inches away. It's a good thing I'm not fat!

Anyway, there are only 6 of us of the original Squadron left. It's pretty awful when you lose fellows wholesale, especially people like Walsh whom one has got to know pretty well'

A letter written by Pilot Officer B. B. Considine to his mother, 6 November 1940, refers.

A well-documented 'Battle of Britain' group of eight awarded to Flight Lieutenant B. B. 'Connie' Considine, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, one of a handful Irish pilots who fought in the Battle, considering it 'his duty' to fight for Britain, who recorded at least two kills in the Hurricanes of No. 238 Squadron during the Battle

Shot down days after the end of the Battle by Helmut Wick - and suffering canon wounds - he was driven to hospital by a grumbling civilian who was worried about his spilling blood on the upholstery; Considine recovered to tow Gliders during 'Operation Varsity' and was later an airline pilot of Aer Lingus

1939-45 Star, clasp, Battle of Britain; Air Crew Europe Star, clasp, France and Germany; Africa Star; Burma Star; Italy Star; Defence and War Medals 1939-45; Air Efficiency Award, G.VI.R. (Flt. Lt. B. B. Considine. R.A.F.V.R.), mounted as worn nearly extremely fine, together with corresponding miniature awards, the miniature Air Crew Europe lacking clasp (16)

Brian Bertram Considine was born on 15 January 1920 in Dublin, the second son of Thomas Ivoy Considine and Dorothy Agnes Cobb. Of Limerick extraction, his father worked as a doctor and served as the Governor of the Central Criminal Lunatic Asylum for Ireland at Dundrum. Similar to Broadmoor Hospital in England, Considine thus spent his childhood witnessing his father attempting to maintain the distinction between criminality and illness under the title of Chief Inspector of Lunacy in Ireland. Educated at Ampleforth College, Considine was passionate about flying and joined the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve in January 1939, quite unperturbed about the political developments across the Channel:

'Well, I was nineteen then and I don't think I was concerned with those kinds of things… I was more interested in enjoying myself!' (Oral History Interview, I.W.M. 10961 refers).

Completing his elementary flight training at Gravesend, Considine was at his mother's apartment in Harrington Gardens, London, when he heard that war had broken out. Called up the day before, he felt a sense of relief that the indecision was over but no doubt held feelings of trepidation having flown just 50 hours in Tiger Moths. Nevertheless, the declaration of war had its compensations:

'I had a glorious month when I was paid by the Air Force and I was also paid by my firm because I was with Unilever as a trainee… So I had a month enjoying myself and playing golf!'

Sent to an Initial Training Wing at Cambridge and then on to Flight Training School at Grantham, he finally completed his course on fighters on 10 May 1940, the day that Winston Churchill became Prime Minister and Hitler launched his blitzkrieg against France and the Low Countries. Appointed to a Commission, Considine was posted to the O.T.U. at Sutton Bridge but arrived amid scenes of 'utter chaos.' With no one knowing what was going on and arriving quite unexpectedly, he returned to Grantham and was then posted to No. 238 Squadron at Tangmere, Sussex.

'No one had heard of it!'

'Kitted up' in London, Considine arrived at Tangmere on 14 May 1940 amid scenes of similar confusion:

'I asked for 238 Squadron and no one had heard of it… Because 601 and 145 were both there - they were both Hurricane squadrons - and we were a new squadron formed at Tangmere, the C.O. was a fellow called Baines who had come from the Air Ministry and the Flight Commanders had come from other Squadrons, and then there were a few of us from Grantham… myself, Wigglesworth, Sgt. Alsop, none of us had had any ops training at all. We found ourselves on this squadron with Spitfires… Four of us hadn't flown anything other than biplanes.'

Recognising the potential for 'lambs to the slaughter', the new recruits were given a flip round in a master trainer by Squadron Leader Cyril E. J. Baines, before being sent off alone in Spitfires:

'Well, of course, it was heavenly!'

Considine was not alone in his praise for the Spitfire, indeed his first impressions were similarly experienced by Pilot Officer Geoffrey Wellum of No. 92 Squadron, Royal Air Force, and recounted in detail in his memoir First Light. Whilst Wellum's first flight resulted in a 'decidedly lumpy' landing, Considine faced far more than disapproving glances from his Commanding Officer:

'My own first flight wasn't very auspicious because they [Spitfire aircraft] had all sorts of technical things we didn't have in Harts and things… For example, you had a variable pitch prop, which meant that you put it into fine pitch to take off and when you got it to a certain height you put it back into coarse pitch.

I promptly forgot to put it in coarse pitch and I did a few circuits around the field and all the rest of it, came back and landed, and feeling pretty pleased with myself - as I'd made a nice landing - I could see the C.O. jumping up and down like a monkey in a rage. I got out and remember him saying:

"I'll make you pay ten thousand pounds", or something…

"You've wrecked the thing!" It was all covered in oil.

Fortunately the engine had managed to survive, and that was that…'

A lot of us were total sprogs!

Considine spent his first days at Tangmere continuing to train under the watchful eyes of Stuart Walsh and Bill Kennedy, the former a 23 year-old Tasmanian-born Flight-Commander who would later be shot down over the Channel and killed on 11 August 1940:

'I remember Stuart Walsh taking me up and seeing if he could lose me - you know, I had to get on his tail and all this sort of thing.'

Transferred to Hurricane aircraft, the Squadron moved from Tangmere to Middle Wallop and was made operational on 2 July 1940. From then on, 'one was constantly in action at that time'. For Considine and his fellow pilots, the experience became ever more frightening the more you realised what was going on. He became very tense waiting to go up:

'You'd be waiting there for the telephone to ring. Every time it rang, you'd go taut… And then you'd run out and go!'

Many pilots grew to hate the sound of the telephone (First Light, refers), it's ringing summoning the men to 'go hell for leather' towards their machines.

Tally Ho!

On 13 July 1940, Considine awoke to an overcast sky, gusty rain showers and a light southerly wind. As conditions improved towards evening, 'Blue Section' consisting of Flight Lieutenant Walsh, Pilot Officer Considine and Sergeant Seabourne took off and succeeded in shooting down a Me. 110 in the Weymouth locality (Operational Record Book, refers). The exact circumstances are described in a letter written by Considine to his mother the following day:

'If you had heard the 9 o'clock news this morning (Sunday) you would have heard a detailed account of our biggest fight yet. There were twelve of us up when we saw two Dornier bombers and about 5,000 feet above them 30 Mess 110 Fighters, 3 of our chaps attacked the bombers, whilst the remaining 9 of us went up to attack or rather engage the fighters - outnumbered 3-1.

I have never been so frightened in all my life!

Anyway, we climbed up into the sun and my Section Leader then turned and dived down at Huns. I followed him down. He attacked one and immediately another one got on his tail. I attacked it, and got one on my tail. However I just forgot about the one behind me and went for the fellow in front of me. I fired at him and he did a quick turn to the left, I turned inside him firing all the time, suddenly his port engine caught fire and he dived straight down into the sea. All this time I had another fellow on my tail pumping lead at me… It was our first really big show and we feel we did pretty well… It was the first machine that I have definitely shot down on my own.'

Two further enemy aircraft were shot down by 238 Squadron, but the mood at Middle Wallop was subdued upon hearing the news of the loss of Flight Lieutenant J. C. Kennedy who stalled trying to avoid high tension cables whilst landing and was killed.

A little over a week later, on 21 July 1940, Considine was firmly in amongst the enemy for a second time piloting Hurricane P.3599 and serving as 'Blue 2' under Flight Lieutenant Walsh. Vectored over a friendly Channel convoy, he intercepted fifteen Me. 110s as they began to dive bomb the hapless merchantmen who sought refuge in Portsmouth harbour:

'Three of us, myself and Sergeant Little who was No. 3, we came on an Me. 110 over Portsmouth… We went into line astern; in those days you followed the book with all those tactical things which were abandoned later on… Stuart Walsh delivered an attack on the 110 and I followed after him and gave it a squirt. The rear-gunner was shooting at me - I gave it a squirt and got (him).

Breaking away, the 110 was finished off by Walsh. It went straight into the water.

We just went straight up their arses!'

According to the ORB, Considine then set the starboard engine of another Me. 110 on fire. Chasing the stricken enemy aircraft all the way back to France, it crashed back at base, killing one of the crew (The Few: The Story of the Battle of Britain in the Words of the Pilots, refers). Credited with a 'Probable', Considine relocated with his Squadron to R.A.F. St. Eval in Cornwall on 14 August 1940 - where it was believed the pilots could take a little time to rest and recuperate in a somewhat quieter sector. He returned to Middle Wallop on 10 September 1940 as was immediately back in the thick of it.

Don't get any blood on the upholstery!

According to the historians, the Battle of Britain ended on 31 October 1940.

"Unfortunately, no one told the Germans," Considine later recalled. Having successfully survived the heat of battle he was shot down by a Me. 109 over Bournemouth on 5 November 1940:

'Well, yes, we were at 20,000 feet. I was at the rear, weaving, keeping an eye out for aircraft behind… And I looked in my mirror and saw a fellow directly behind who I thought was a Spitfire because 609 Squadron were supposed to be behind us - but of course it wasn't a Spitfire, it was a 109 and just as I saw him he fired. I heard a noise and everything exploding in the cockpit…

I banked over, pulled down hard, tried to do a half-roll, and I could smell the cordite in the cockpit. And of course I shouted out on the R.T. to warn the Squadron… The fellow in the middle, Jackie Mann, says he saw this fellow who was only a few yards behind me… And he must have blown the tail nearly off because I couldn't fly the aeroplane. And so I baled out. I kicked open, I got the canopy open, went to get out, released my belt - but I hadn't pulled out the radio connector… So I had to give it a kick to get rid of that.

But I couldn't get free of the aeroplane. It had gone into a spin and was above me. It really was quite bothersome!

I had to do a delayed drop and didn't pull the ripcord until I go to about 3000 feet and broken cloud. As I pull the ripcord the aeroplane went hurtling past me with a terrific roar… The engine was still on of course! Quite queer this thing pursuing me down…'

The ORB notes that Considine was wounded by cannon fire in the wrist and leg and came down by parachute at Sturminster Marshall. His aircraft, Hurricane V.6792 was wrecked at Shapwick, not far from the wreck of Sergeant Josef Jeka who came down at Wimborne. Bleeding profusely, Considine made his way across ploughed fields to the nearest road where he flagged down a passing motorist:

"This is a new car and it's got to last me the war," grumbled the driver.

He was driven to hospital.

For Considine, the event served as a giant wake-up call. He had survived the full loss of hydraulics when shot at from behind by a Me. 109 on 6 August during a 700-aircraft raid on Portland, but the loss of his aircraft led to some deep thinking and careful analysis, not least in his mistaken belief that the trailing aircraft was 'friendly'. In a letter to his mother written from the Officer's Ward at Shaftesbury Military Hospital on 6 November 1940, Considine noted:

'Thank god the thing didn't go on fire. It took me so long to get out I would have been horribly burned. I'm a bit shaken and bruised of course, and I've got these minor wounds, but I feel very well and in good form, so don't worry about me.'

It was many decades later that he learnt, with some satisfaction, that the Luftwaffe pilot who had shot him down was the then top-scoring 'ace' Helmut Wick (56 victories) - who was himself shot down by John Dundas, elder brother of Hugh 'Cocky' Dundas, off the Isle of Wight.

Further service: Middle East & Operation Varsity

Remaining with No. 238 Squadron, Considine transferred to Damascus and Habbaniya aboard the M.V. Highland Princess on 9 May 1941. From here he initially ferried fighter aircraft for Squadron use in the Western Desert, before joining the Meteorological Flight in Palestine on 27 February 1942. Transferred to No. 74 Squadron at Tehran on 30 January 1943, he flew operational patrols in Spitfire aircraft over Catania from 18 July 1943, being heavily engaged in escorting Mitchell and Kittyhawk aircraft. A scramble on 12 August 1943 notes, 'Bandit turned away - no contact.'

Joining No. 111 Squadron in Malta from 1 July 1943, he subsequently transferred to No. 173 Squadron as an Instructor in late 1943. It was at this time that Considine had the distinction of taking up Air Vice Marshal Sydney E. Toomer on a dual instruction flight aboard a Fairchild aircraft on 13 and 14 December 1943.

On 30 August 1944, he was further tasked with transferring the G.O.C. in C., Sir Bernard C. T. Paget, from Heliopolis to Mutrah. Sent to India with his Squadron, he carried out supply drops in Burma before returning home on 24 January 1945 and being sent on a refresher course at No. 17 S.F.T.S. based at Coleby Grange, Lincoln. Graded 'above the average', he was posted to No. 48 Squadron in France and spent March 1945 flying regular sorties on Dakota Aircraft. This included towing a glider over the River Rhine on 24 March 1945 as part of Operation Varsity, his log book noting 'Glider tow over Rhine. Landed Lille.'

Post-War career

Considine made his final flight with No. 48 Squadron on 15 November 1945. Released from the service, he took employment with Aer Lingus for four years flying Viking and DC-3 aircraft between Dublin and London. He left the airline in 1949, his civilian log book noting over 3000 hours solo flight time, but not before whisking away a young Aisling 'Nuala' Kiernan who worked as an air hostess for the airline.

The couple married and Nuala later developed a lucrative side line compiling crosswords for a range of newspapers. Joining the press and puzzles agency Morley Adams Ltd, it is believed that over seven decades she compiled more cryptic crosswords than anyone else in history. In the meantime, Considine took up careers in advertising and journalism; it was said that after he left Aer Lingus he had completely lost his enthusiasm for flying, and on winter trips across the Atlantic they always travelled by boat.

In his spare time Considine played cricket for Ampleforth and became a successful member of the Royal Mid-Surrey Golf Club located in the Old Deer Park, Richmond, London. In 1964 his handicap dropped from 12 to 3 - a remarkable feat on the testing J. H. Taylor course. Perhaps unsurprisingly given his ability to 'regularly break 70' (Times Obituary, refers), he won the prestigious Royal Air Force Golfing Society Veteran's Handicap Cup in 1985. Considine died without issue in London on 31 March 1996.

Sold together with an outstanding archive of original documentation and ephemera including:

(i)

Royal Air Force Pilot's Flying Log Book No. 2, the opening page annotated by the recipient 'Continued from Old Book Lost Western Desert. 30/12/41', detailing the flying operations of Considine from 12 February 1942-14 October 1946. The log includes a full review of operations in the Middle East, Burma and his preparations for and participation in Operation Varsity on 24 March 1945. The back pages include a full record of service from 12 January 1939-15 January 1946, including a wide variety of aircraft flown - including the Spitfire I, Spitfire V, Spitfire X, and Hurricane Mk. 1 and Mk. 2 - and a record of the 30 Countries visited during the war.

(ii)

Ministry of Civil Aviation C.A. Form 24 Personal Flying Log Book (Aircraft Operating Crew), annotated to inner cover by the recipient, 'B. B. Considine. Aer Lingus TTA, Dublin, Eire', containing a full record of civilian flights from 2 October 1946-25 November 1949. This log book records approximately 550 separate flights, the majority as Captain of a DC-3 Airliner flying from Dublin-Shannon, Dublin-Liverpool, and Dublin-Glasgow.

(iii)

Original Notice to a Royal Air Force Volunteer Reservist to join for Service in the Royal Air Force, named to '742748 Sgt. B. B. Considine, 55, Harrington Gardens, London, S.W.7.', dated 1 September 1939.

(iv)

A fascinating collection of sixteen handwritten letters compiled by the recipient to his mother, many with original envelopes of transmission, dated 14 July 1940, the second undated but written whilst stationed at R.A.F. St. Eval (14 August 1940-10 September 1940), 28 August 1940, 30 October 1940, 6 November 1940, 15 January 1941, 6 February 1941, 1 April 1941, 5 April 1941, 2 July 1941, 10 July 1941, 4 January 1942, 28 January 1942, 22 June 1943, 8 July 1943 and 26 July 1943.

These letters give a thorough insight as to the life of a Battle of Britain Pilot of No. 10 and No. 11 Groups at the height of the Battle, followed by detailed accounts relating to his service, comrades, health and hopes for the future; a very 'personal' insight, including the following references:

14 July 1940:

'Well, we've done several convoy patrols and we have raids all the time down here. We get sent up to intercept them and patrol certain places like Portland Harbour. We were up this time it was bombed the other day. We only found one Me. 100 though. 3 of us went for it and fired at it; tried to get away and fired off this hell of a lot of stuff which was going past my port wing. Suddenly one of his engines went on fire and he dived straight into the sea.'

From the Officer's Mess at R.A.F. St. Eval, Cornwall:

'I have been swimming twice since we have been here and having a grand time. I'm still hoping and hoping to have some leave, but it's hopeless… Nobody in the Squadron has had any leave since we were formed. Anyway, there are only 6 of us of the original Squadron left.

Wigglesworth makes himself more and more unpopular every day, the way he always tries to get out of things and shirk duty. To top it all he has applied for an instructor's job, he doesn't like the fighting, none of us do, and we are continually struggling to get pilots and he is struggling to leave.'

28 August 1940:

'The restful time we are having down here is really rather funny as the Huns have been over several times trying to bomb us to blazes… The night before last they dropped about 100 bombs and thousands of incendiaries all around us, so far they haven't done any damage at all… We have been getting so little sleep though.'

30 October 1940:

'I most certainly couldn't stand the idea of allowing Eleanor to join the W.A.A.F. I don't think I would be exaggerating when I say that it would be a very dangerous step, and would have her open to ruination and all sorts of horrid things with which I don't want any sister of mine to come in contact. It is all very well saying she has her head screwed on the right way… But I would feel most unhappy about her and I'm sure you would too if you knew as much as I do about the W.A.A.F.s - I know that there are a lot of "nice" girls among them, but this is their peril, and though I am not saying that Eleanor will necessarily be corrupted by the bad influences with which she will undoubtedly come into contact, I don't think it is fair to put her in the way of them…

I am very well despite the cold. I have given up smoking and drink very occasionally which I daresay is a good thing. Wigglesworth has been slung out. I feel awfully depressed today, don't know why, I'm fed to the teeth with the war.'

6 November 1940:

'I have been remarkably lucky as I only got some cannon shrapnel in the hand and leg. The pieces are so minute that they are not going to bother to take them out… I got taken from behind by a 109. The aeroplane was spinning like hell and the 109 gave me another burst… Don't worry about me… The most exciting thing that has happened to me.'

6 February 1941:

'We are expecting an even more intense blitz than last time, and are looking forward to it with mixed feelings! I see that the Americans say that 50% of us will go, but we will wipe the floor with the Huns and leave them helpless. Anyway, we are having a sweep on it and whoever draws the right horse will get approximately £36.'

28 January 1942:

'I spent my 22nd birthday in the middle of the Red Sea, and celebrated in the usual way. I feel I'm getting quite an old man now! Frankly I'm tired of it all and want to go home.'

26 July 1943:

'Here in Sicily is most peculiar. The local population are not entirely hostile nor friendly, but appear to be more frightened than anything else. There is an abundance of eggs and fruit of all descriptions and everything is amazingly cheap - so far!

(On the other hand)… I wouldn't like to be left alone without a gun. I have heard that if they can get you and they think they can get away with it, they'll let you have it. It leaves one with a vaguely uncomfortable feeling… Now that Mussolini has resigned I wonder what will happen. I am feeling a bit optimistic about the war.'

(v)

An original typed letter from the Director of Personal Services at the Air Ministry to the recipient's mother at Harrington Gardens, London, dated 7 November 1940:

'Madam,

I am directed to inform you that your son, Pilot Officer Brian Bertram Considine, was slightly injured during air operations on 5th November, 1940. As his condition is not stated to be serious, no further reports are expected, but should any be received you will be informed as quickly as possible.'

(vi)

The recipient's 1939-45 War Compliments slip, noting full entitlement, additionally annotated to reverse by recipient '+Air Efficiency Award'; An original copy of The Daily Mirror dated 30 August 1940, bearing an image of the wreck of a German aircraft titled 'Examining the propeller boss of a German raider brought down on the moors in south-west England,' - additionally annotated in pen by Considine 'That's Me', with an arrow pointing to a Pilot standing by the wreckage, the newspaper in average condition, heavy yellowing and frail, but a rare souvenir; Copied Operations Record Book reports from 12 May 1940-7 November 1940, including records of flights, contacts with the enemy and an account of the shooting down of Considine; a copy of The Times obituary for Considine, dated 30 April 1996.

(vii)

Original Pilot's Flying Goggles, of Battle of Britain vintage, as worn by the recipient during the Second World War, in good condition.

(viii)

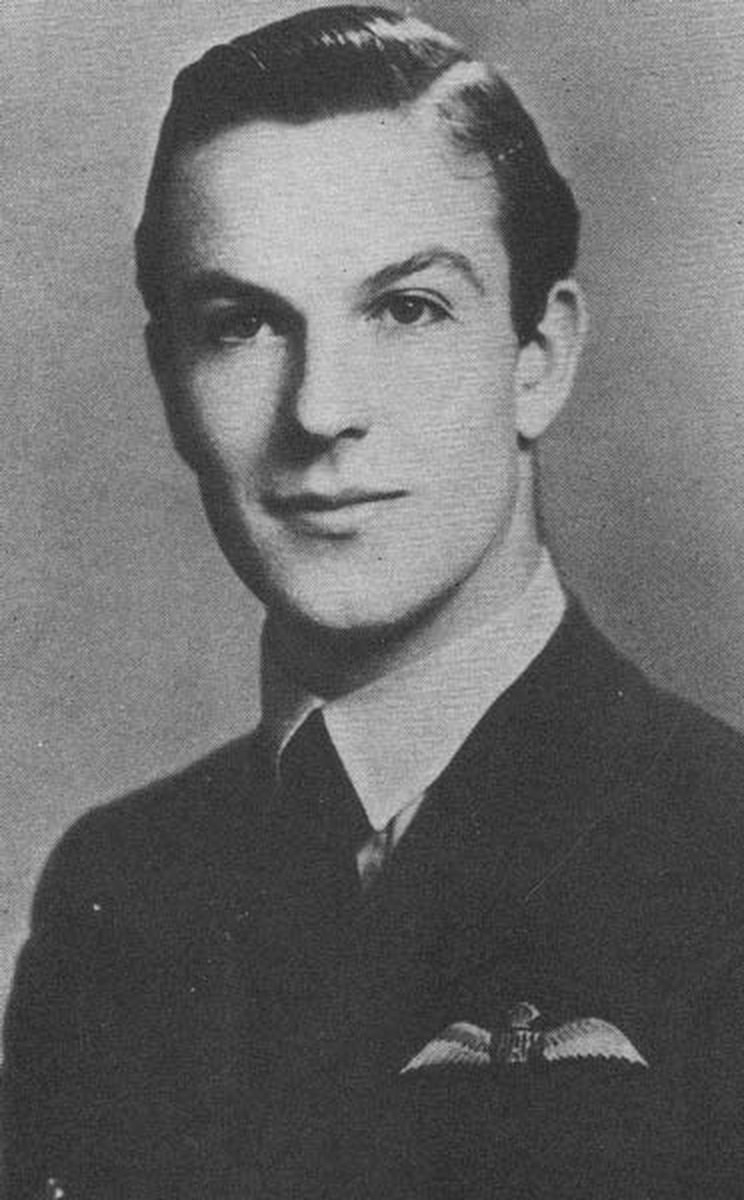

Four contemporary postcard photographs of the recipient, some with fellow Pilots, together with the original image as used by The Daily Mirror, and a fine large portrait photograph of the recipient.

(ix)

The Battle of Britain "The Few" leather-bound album, as gifted by Flight Lieutenant J. H. Holloway to Flight Lieutenant B. B. Considine.

(x)

His leather and sheepskin flying jacket, faint ink inscription to belt, wear commensurate with age and service. It is interesting to note that the Hurricane provided its Pilot with no heating and they were described by many as the coldest aeroplane they ever flew.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£6,500

Starting price

£5000