Auction: 19003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 312

Family group:

'It is an honour to have a small part in a ceremony honouring such a remarkable young man.

Jack Conway Carpenter was obviously one of those resourceful, eager Canadians who won acclaim for their country wherever they went. We can take such pride in the knowledge that Canadian pilots such as Sub-Lieutenant Carpenter were in the thick of the Battle of Britain. We do, however, very much regret that such promise and talent were lost so early in life.

The service record of the Carpenter family is truly impressive. Jack enhanced that wonderful tradition; there can be no finer epitaph.'

George Hees, Minister of Veterans Affairs

'In the eyes of the world the Battle of Britain is, and always will be, an R.A.F. victory and the contribution and sacrifice of the 'Few' is something that is indisputable. However, the Royal Navy, and those with an interest in Naval aviation history, should never forget the bravery of the few within the 'Few' who fought in Naval uniform.

Seven Naval pilots were killed and two wounded during the Battle of Britain and whilst all 56 Naval aviators are listed on the Battle of Britain memorial in London, the contribution made by the Royal Navy is rarely recognised. In the iconic films 'Battle of Britain' and 'Reach for the Sky', despite Douglas Bader having three Naval officers in his squadron, including his wingman 'Dickie' Cork, no reference is made to them.'

The Fleet Air Arm Officers' Association website, refers.

The poignant campaign group of five awarded to Sub-Lieutenant (A.) J. C. Carpenter, Fleet Air Arm, one of the Senior Service's 'few within the Few' who flew Hurricanes of No. 229 and 46 Squadron at the height of the Battle of Britain - besides this he was one of a handful of Canadians who flew during the Battle and the first graduate of Upper Canada College to lose their life during the Second World War

Having bagged a Me110 near Southend on 3 September and a Bf109 near the Isle of Sheppey on 5 September - a pair of stunning dogfights which are illustrated in detail in his Combat Reports - he lost his life aged 21, on 8 September, when his parachute failed to open after bailing out - he would number as one of just seven Naval pilots to make the ultimate sacrifice during the Battle of Britain

It is perhaps strange to relate that it would only be on the 47th anniversary of his loss that the Canadian High Commissioner in London, via the Minister of Veterans Affairs and with an announcement across Canada, finally bestowed his Memorial Cross upon his family

1939-45 Star, clasp, Battle of Britain; Air Crew Europe Star; Canadian Volunteer Service Medal, with overseas clasp; War Medal 1939-45, Canadian issue in silver; Canadian Memorial Cross, G.VI.R. (Sub/Lt. J. C. Carpenter.), together with the recipient's Upper Canada College, Toronto prize medal, nearly extremely fine

The campaign group of five awarded to Regimental Sergeant-Major F. N. Carpenter, Royal Canadian Regiment, late Lance-Sergeant, Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry

Queen's South Africa 1899-1902, 2 clasps, Transvaal, South Africa 1902 (5914 L. Sjt. F. Carpenter. D. of C. L. I.); British War Medal 1914-20 (19249 W.O.Cl.1 F. N. Carpenter. 9-Can. Infy.); Defence Medal 1939-45; Delhi Durbar 1911 (4819. Sergt. F. N. Carpenter. R.C.R.); Permanent Forces of the Empire L.S. & G.C., G.V.R. (R.S.M. (W.O.) F. N. Carpenter. R.C.R.), good very fine (10)

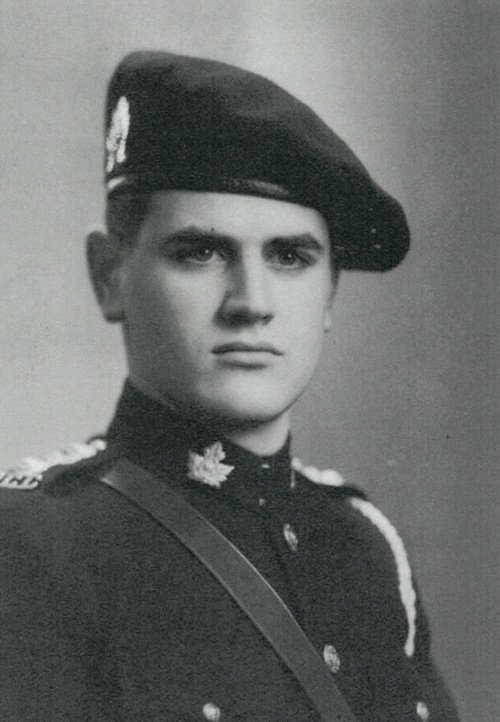

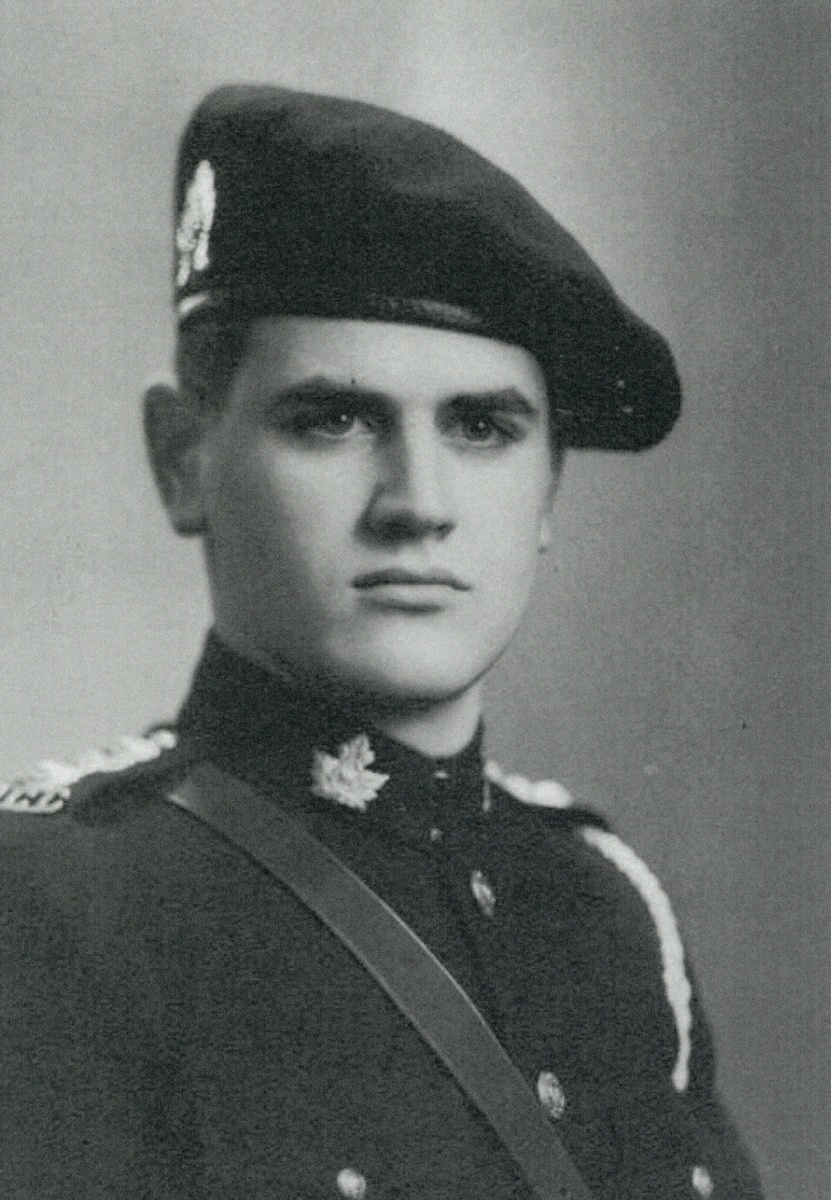

Jack Conway Carpenter was born in 1919 at Toronto, Canada, and educated at Upper Canada College, winning the Gold Medal from that famous institution. He left Canada in 1938, having been a Cadet in his homeland, to attend the Royal Naval College, Greenwich and was commissioned Midshipman (A.) on 1 July 1939 and promoted Acting Sub-Lieutenant (A.) on 1 September.

Battle of Britain

The involvement of Fleet Air Arm pilots in the Battle of Britain in the summer of 1940 is little known. To reference the Fleet Air Arm's Officers Association website, Winston Churchill's famous words of praise for the 'Few' 'immediately conjure up images of plucky R.A.F. chaps running to their Spitfires to go and give 'Jerry' a damn good thrashing. However, it is frequently overlooked that 56 Fleet Air Arm pilots also took part in the Battle of Britain with four becoming fighter aces. Although rarely acknowledged, three Naval pilots also flew with the famous 242 Squadron commanded by the legendary Douglas Bader.'

The young Naval aviators who took part in the Battle of Britain between July and October 1940 saw some of the fiercest fighting of the battle: 23 Naval pilots served with twelve R.A.F. Fighter Command Squadrons, flying Spitfires and Hurricanes, and a further 33 served with 804 and 808, the two Fleet Air Arm 'Battle of Britain Squadrons' who operated under Fighter Command, providing dockyard defence.

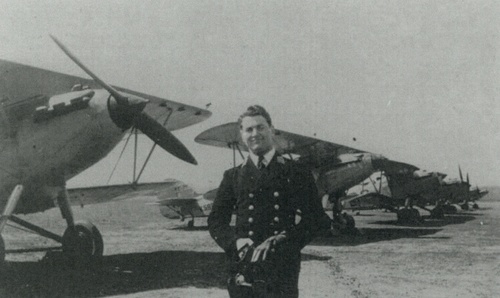

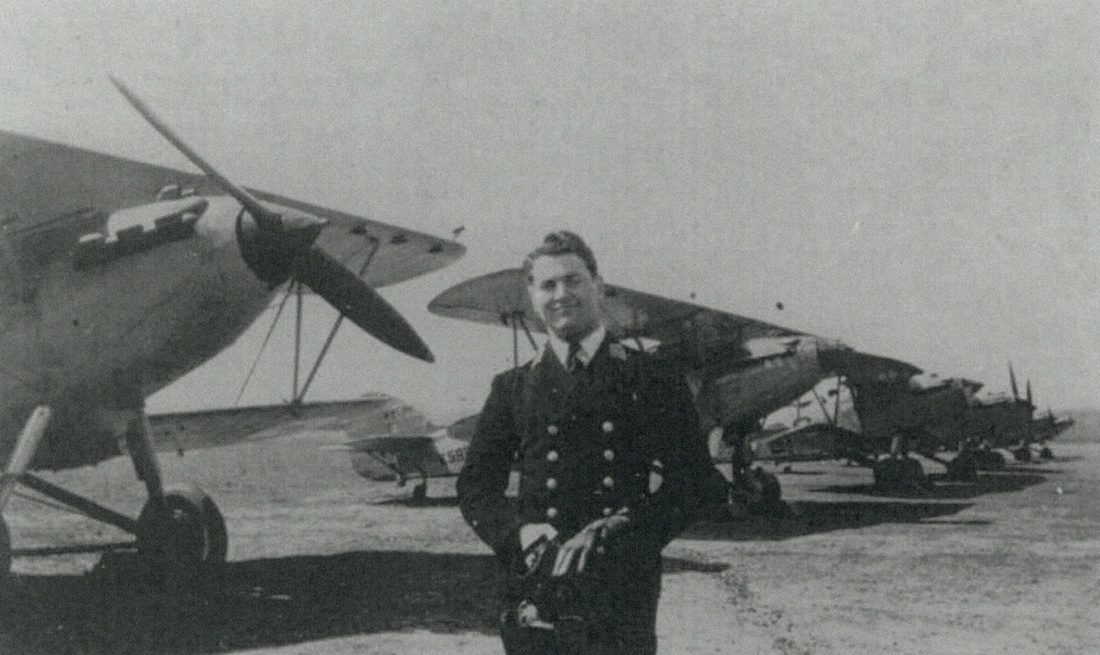

Carpenter was attached to the R.A.F., taken from the carrier Daedalus, from 15 June 1940 and confirmed in his rank on 7 July. Two days later, and just 24 hours before the battle began in earnest, he joined No. 229 Squadron at Wittering flying Hurricanes. He remained similarly employed until removing to No. 46 Squadron, two weeks later.

In common with his fellow F.A.A. pilots who joined frontline R.A.F. squadrons, he would have retained his naval uniform - and was paid by the Admiralty - but in all operational respects he became a member of his R.A.F. squadron. Nonetheless, he and his fellow F.A.A. pilots retained their identity as naval aviators: Sub.-Lt. (A.) R. E. Gardner painted Nelson's 'England Expects' flag hoist on his 242 Squadron Hurricane, and Sub.-Lt. (A.) A. G. Blake with 19 Squadron predictably gained the nickname 'Admiral'.

Bloody nose and a brace for the bag

The first few sorties held plenty of action for Carpenter, for he disclosed the following experience of a dogfight to his brother, Fred (who himself went on to become an Air Vice-Marshal):

'I came as close to a sticky end this morning as I hope for some time to come. I stood a good chance of being crushed by thousands of tons of aeroplane, or burning to death, or as an easy alternative just jumping out and hoping my parachute would open.'

His fears on that parachute were not unfounded as we will discover but on this occasion Carpenter took the option of crash landing, finding a suitable farmers field which he 'ploughed' into, at the cost of a bloody nose.

The Combat Report of 3 September takes up the tale, with Carpenter in 'A' Flight, Blue 2:

'At 0955 hours 12 Hurricanes of 46 Squadron left Stapleford to patrol Rochford at 20,000 feet and intercept enemy raid 45. They encountered about 30 Dornier 215s and Ju88s, flying in six of 5 line astern at 15,000ft, escorted by about 50 Me110s and Me109s. E/fighters were on the starboard side of, and astern of, e/bombers and were stepped up to 2,000ft. The formation we encountered about 6 miles west of Southend, flying west north west.

'A' Flight attacked the bombers from the beam, and 'B' flight attacked the fighters but only a few of the bombers were detached, the main formation proceeding to bomb North Weald Aerodrome.'

Carpenter's own Combat Report:

'At 1020hrs e/a sighted flying in large formation at 200mph WNW. E/A had dark upper surfaces, lower surfaces duck egg blue. Black crosses on the fuselage and wings. E/A 2,500ft below broke up formation slightly as they observed us dive to attack. I made a keen attack on a Do215 which had broken away from the formation. My first burst appeared to miss and I dived under his port wing to about 2,000ft below. I then climbed and when almost level with the enemy I noticed an e/a single engine machine, probably a Me109 on my tail which I shook off by making a steep turn to the left and then noticed a twin engine e/a heading east.

I came up to about 350 yards on his starboard and gave him a short burst. He dived and I followed and gave him another short burst. He appeared to gain on me and pulled out at about 1000ft. I pulled out slightly above him, manoeuvred into position on his tail and gave him a long burst. He lost height and speed, I overshot him and turning - saw the e/a land in a field with his undercarriage up and go half way through a hedge. I turned around, saw the crew get out and as he appeared to be dragged out presumed he was wounded. A farm hand approached the crew and then ran across a field to a farm house. When I went down again to investigate two members of the crew waved and as I saw that they had offered no resistance to the farm hand I climbed up and identified the position, as 4 or 5 miles south of Malden, Essex and returned to base. This e/a was a twin engine, twin rudder and was either a Do215 or a Me110. No fire was experienced from the e/a.'

He was credited with an Me110 and with no such rest for these gallant airmen, was again in a formation of 8 Hurricanes which took off from Stapleford at 1455hrs on 5 September. They engaged a formation of some 15 bombers that had an escort of 23 Me109's. Carpenter again played his part to great effect:

'At about 1520 I was following P/O Johnson at 15,000ft over Gravesend when he spotted a Me109 on the tail of a Hurricane. He dived to the attack and I followed and noticed another Me109 trying to get on Johnson's tail, and saw it fire a burst before I could open fire. When the Me109 saw that I was his opponent he tried to avoid me by turning to the right but I could turn inside him and fired a few short bursts which apparently had no effect as he then put the Me109 into a vertical dive. I found it quite east to pull out above him. In the moment, however, he pulled away from me very quickly. He then turned over onto his right side and I caught up to him and fired again. Then he went into another dive directly over Gravesend.

I followed him and found that he had pulled out at about 50ft and I fired more short bursts. Eventually a piece of material came off the port side of the Me109 and then shortly afterwards I saw some coming out of his starboard radiator. I followed him at about 40 or 50ft above the ground occasionally firing short bursts. The Me109 then went down to about 3ft above what I later discovered to be the river between Sheppey Island and the mainland and when Sheppey Island was joined by two more Hurricanes one of which got in between the Me109 and myself so that I was unable to fire. This Hurricane got in one or two short bursts and was spiffed off by the Me109s slipstream as I was able to manoeuvre into position to fire one more short burst which set the 109 alight.

The Me109 turned onto its port side and crashed in flames in a field in the middle of the Island of Sheppey.'

The Squadron had three Me109's to their name that day, with Pilot Officer Johnson claiming the third before being forced to land at Detling.

Journey's end

Carpenter's final flight would take place just three days later, when he was with the 12 Hurricanes who got 'wheels up' at 1130hrs. Having flown at 10,000ft and rendezvoused with No.504 Squadron over North Weald, they met some 90 Dornier 215's in three sections at approximately 1215hrs. The section had a large fighter escort of Me109's and 110's and the Allies attacked from starboard beam above and in front while the enemy were flying North-North-West. Having drawn the escort into a battle, a huge dogfight ensued over the Isle of Sheppey, a happy hunting ground for Carpenter just 72 hours prior. His trusty kite, P3201 was shot down around 1230hrs and Carpenter took to his parachute. Tragically, as he had almost predicted in his previous note, it failed to open and he fell to his death over Sheppey. P3201 crashed near Bearsted, Maidstone. His body was taken to the Royal Naval Dockyard, Chatham, before being transferred to his family who had returned to their ancestral home at Llanfaethlu, Anglesey. Carpenter was to be buried at sea from a Royal Navy minesweeper in the presence of his father on 16 September 1940.

He was one of a handful of Canadians to fly in the Battle of Britain and is commemorated on the Fleet Air Arm Memorial, Lee-on-Solent. As his father served in the United Kingdom it appears the Canadian Memorial Cross was not claimed at the time and via the Canadian Department of Veterans Affairs this was put to rights. On the 47th Anniversary of his death, at Canada House, London, the Cross was presented to his eldest brother by the Canadian High Commissioner, Roy McMurtry; sold together with the original ceremony Immediate Release (No.887) document, the covering letter signed by George Hees and copied research.

Frederick Noel Carpenter was born on 31 December 1881 at Lichfield, Staffordshire and served initially in the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry. Having seen active service in South Africa (QSA & 2 clasps) he was discharged on 19 October 1907, before emigrating to Canada. Carpenter took little time in enlisting in the Royal Canadian Regiment on 7 November 1907. Setting up home in Toronto, he spent several happy years in the military, rising to become Sergeant-Instructor by 1913. At the outbreak of the Great War he enlisted in the 9th Canadian Infantry and sailed from Quebec for Europe on 3 October 1914. Promoted Company Sergeant-Major Instructor on 6 January 1915, he spent the remainder of the war offering essential training to recruits destined for the Western Front. Carpenter was sent to Bath in April 1916 as a Physical Instructor, to Aldershot in May 1916 as a Bayonet Fighting Instructor and served at the Canadian Hospital, Buxton in July 1916. By war's end, Carpenter had been 'mentioned' for his valuable services (London Gazette 14 August 1918, refers), promoted to Regimental Sergeant-Major and awarded a well-deserved L.S. & G.C. Medal on 18 September 1918. Discharged in late 1919, he went on to instruct in the OTC at Upper Canada College and would surely have given instruction at some point to his gallant son; sold together two calling cards and copied research.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£8,500

Starting price

£2800