Auction: 19002 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 369

'Charles Blackburne came into my life and went out of it in the short space of two years, but remained from first to last the same.

Hand in hand with his beloved children, he held fast to the high and noble faith which assures them of his eternal watch over the beloved ones he leaves behind.'

Field Marshal J. D. P. French, 1st Earl of Ypres, writing of the loss of his friend.

An outstanding and deeply poignant Boer War D.S.O. group of six awarded to Lieutenant-Colonel C. H. Blackburne, 5th Dragoon Guards, late West Kent Imperial Yeomanry, who served with distinction during the Boer War and witnessed the retreat from Mons, earning a brace of 'mentions' in the process

Having been severely wounded and all but crippled in the left arm and shoulder at Ypres, he drowned attempting to save the lives of his children aboard the torpedoed R.M.S. Leinster in the closing weeks of the war

Distinguished Service Order, V.R., silver-gilt and enamel, with integral top riband bar; Queen's South Africa 1899-1902, 3 clasps, Cape Colony, Transvaal, Wittebergen (7447. Capt: C. H. Blackburn, 36th. Coy. 11th Imp: Yeo:); King's South Africa 1901-02, 2 clasps, South Africa 1901, South Africa 1902 (Capt: C. H. Blackburne, Imp: Yeo:); 1914 Star, copy clasp (Capt: C. H. Blackburne. D.S.O. 5/D. Gds.); British War and Victory Medals with M.I.D. oak leaves (Bt. Lt. Col. C. H. Blackburne), the rank to second privately altered, latter part of surname to Victory Medal officially re-impressed, otherwise good very fine, housed in an old fitted open-fronted glazed wooden case, together with silver cap Badges for the Queen's Own (West Kent) Yeomanry and the 5th Dragoon Guards (6)

D.S.O. London Gazette 31 October 1902:

'In recognition of services during the operations in South Africa.'

Charles Harold Blackburne was born on 20 May 1876, the third son of Charles Edward Blackburne, who died prematurely aged 32 at Hastings, with young Charles just 18 months old. His mother Mary, daughter of the late John Riley of Oldham - a well respected mill owner of that locality - decided to settle the family there. Mary and her new husband, William Shadforth Boger, welcomed a half-sister in 1885.

Nurses and dentists on high alert

From infancy, Charles was healthy, strong and big, but also restless and full of mischief as recalled in A Memoir by the Brother:

'His was always an inquiring mind, and he set about discovering things at an early age. For example, he wanted one day to discover if the key used to wind up a clockwork mouse was a good thing to eat, and so of course he swallowed it, much to the consternation of nurses. Then, when he possessed them, he was anxious to know all about his teeth, and so he proceeded to pull them out in order to look at them. His dental exploits continued for some years, for his first second tooth he uprooted one night with the aid of a button-hook and penholder, and he was considerably surprised and pained that the discovery of a tooth with a long root, a novel thing to him, proudly displayed at the breakfast table the following morning, did not meet with an enthusiastic reception.'

Charles displayed little natural inclination for book-learning and the 'drudgery' of the Latin and Greek Grammar was 'well-nigh intolerable to him'. On the other hand, animals, in particular horses, were a great passion. His toys were almost all of an equine nature, and, once he had learnt to read, he read Swiss Family Robinson cover to cover, the well-thumbed contents appealing to his interest:

'How many times that precious volume was read through who can say? It used to be a family joke, for several years, that it was the only book he had read through.'

Soon after the death of his father, financial losses made it necessary for his mother to put down her carriage and send away the much beloved pony. An annual visit to an uncle - who always had the best of hackneys in his stable - soothed the loss, and Charles soon learned to ride, facilitated by an elderly and much loved coachman. Charles also developed a wonderful 'eye for a horse' and he often attributed this skill to his uncle.

Tonbridge days: First rate shot - second rate 'swiper'

Educated at Upper St. Leonards School and, from September 1890, Tonbridge, where he fell under the watchful eye of his Housemaster, the Reverend A. Lucas. Academically, his progress was steady if not spectacular:

'I do not know if modern schools cater for boys of his natural genius, I hope they do, for I am certain that if Charles could have been delivered from the dry and dull world of Grammar and Syntax; if he could have been taught Natural History or Natural Science; if, in a word, the school curriculum had been more elastic and less pedantic, he would have greatly benefitted by his school days. For Charles had a great respect for learning, and he was a bright and clever lad. But, as things were then, he by no means distinguished himself at school.'

Though he never rose higher than the Fifth Form, it is greatly to the credit of his Housemaster that he was made a House Praeposter contrary to the 'usual' tradition of selecting older boys. The equivalent of prefect, Charles's 'infectious happiness' no doubt secured the role.

Having displayed a good eye for shooting at Tonbridge, the slow pace of cricket somewhat dulled his interest in the game:

'He could not resist the temptation to "swipe", and so, after one or two mighty blows, his innings usually came to an end and he speedily returned to the pavilion, where he was always heartily and uproariously welcomed.'

A good athlete however, Blackburne won both the Junior and Senior half-mile races at the School Sports. He was also a useful three-quarter back, being awarded his 1st XV colours. After a number of happy years, he departed Tonbridge at the end of the Easter Term 1893, when aged 17 and a half.

Returning home, Charles was encouraged by his mother to consider a profession fitting for a young man of standing, such as the Army. Instead, he and his brother Lionel took on a large farm near Penshurst, Kent, and set about horse-breaking:

'No youngster was too wild for him, no "rogue" too confirmed in bad habits for him to tackle.'

One particular hackney caught the eye of Lionel:

'She was fiery and vicious, most uncertain in temper, and possessed of most of the bad habits of the stable. She would bite and kick any stranger who came into her box, and woe betide the unwary horseman who should presume to ride her. But with him (Charles) she was docility itself, as quiet as the proverbial lamb.'

At this time too, Charles also developed a wonderful gift as a dog trainer. Spaniels, retrievers, terriers, all quickly learnt from him those things without knowing which no dog is worth his place in the kennel!

In 1895 Lionel departed to go up to Cambridge, whereupon Charles decided to try his hand at chicken farming. It was not to be a fruitful venture, indeed the prosaic means to earning a living dulled his senses and brought his time in Norfolk to an end.

Going for gold

On 12 May 1898, Charles travelled to the Klondyke, enjoying many expeditions duck shooting on the banks of Lakes Winnipeg and Manitoba. He later visited Alaska together with two Englishmen and took a 'claim' on a small piece of land which was hoped would contain gold deposits:

'He got to the claim, only to find it "jumped." Poor Charles! He was doomed to meet with no good luck in Alaska.'

Unperturbed, Charles took work as a barman at Surprise Lake, later becoming Manager. Making a second attempt to 'strike' gold at Cape Nome, reaching Dawson City on 3 August. He writes:

'By the way, to give you some idea of the gold in this Country, I am sleeping in a cabin with another man who is taking two tons of gold for the banks. He and I are the sole convoy. Not many can say that they have slept for a week over two tons of solid gold.'

Sadly, despite witnessing the wealth garnered by others, especially those involved in feeding and clothing prospectors, such success eluded Charles. Working with pick and shovel for two months at Nome froved 'a pretty rough time', and somewhat deflated, he returned to Victoria and his true passion - horses - winning the Colwell Cup steeplechase. He landed home at Liverpool, via New York on 21 December 1899.

Down south

On 9 January 1900, Charles attested as a Private in the West Kent Imperial Yeomanry and was posted to the 11th Battalion under Lieutenant-Colonel Firman. After a little under two month's training, he embarked aboard the S.S. Cymric arriving in Cape Town on 28 February 1900. Sent to Maitland Camp at the end of March, it was here that he learned of the serious illness of his elder brother Jack, who was struck down by enteric fever. Jack had gone out to South Africa as Adjutant to the Irish Hunting contingent of the Imperial Yeomanry under Lord Longford. It was whilst visiting his brother that Charles began to impress the officers of the Irish Imperial Yeomanry, likely on account of his equine knowledge. Offered his brother's commission by Lord Longford, Charles made clear his desire to accept upon the understanding that the Irish Imperial Yeomanry would take on another brother, Harry, fresh from Cambridge, who was with the 11th Battalion.

Disappointingly, the project fell through and Charles soon found himself 'breaking-in' a four-in-hand for the waggon. As fate wound have it, it was just as well that it did - The Irish Hunting contingent were later almost entirely captured by the Boers at Lindley in June 1900.

Serving at the Battle of Biddulphsburg and promoted Lance-Corporal, he wrote whilst on scouting duties:

'We had to storm a hill with almost straight sides. The pluck of our soldiers is perfectly wonderful. The Scots and Grenadier Guards went into the hottest of the firing smoking pipes and biting straws, just as if they were going partridge shooting. The veldt was on fire in places and many of the wounded as they fell were dreadfully burnt.'

The 11th Battalion, Imperial Yeomanry, were attached to the 8th Division under General Rundle, known as 'The Starving Eighth', on account of poor transport arrangements and being a long distance from railways, their food was very scarce. Charles, and the other mounted troops were somewhat more fortunate than the infantry, being able to procure chickens from the locals. Promoted Sergeant in June, he was fortunate to escape a Boer ambush, leading his 12 men with much success. On another occasion he witnessed the Boers shell five hundred or more terrified horses and was somewhat relieved to witness Harry stumble to his feet having had a close shave not with a Boer bullet, but with a rather awkwardly placed stone.

In October 1900, the 8th Division was split up and Charles was posted to Reitz with General Boyes' Brigade. The next month he saw almost daily fighting in the Standerton neighbourhood, being commissioned and afforded a 'hearty welcome' to the Officer's mess at Standerton by the Honourable E. Mills, Sir Samuel Scott and Captain Bertram Pott. The following December, Charles, in charge of two troops, found himself in a considerable scrap:

'The other day we had a good fight. We found the Dutchman in possession of a high kopje with a gun and two maxims. The mounted troops took the kopje.'

Two months later, in January 1901, Sir Samuel Scott returned home leaving Charles and Bertram Pott in charge of the whole squadron. Suffering a further month of sniping and sickness, the Regiment were finally transferred to Ficksburg for rest. In September, following endless marches and sniping, Charles finally succeeded in gaining a more permanent position, being placed in command of a post named Albertina. Relieving the 14th Hussars, he oversaw 170 men and horses and was instrumental in keeping Boer activity in the area to a minimum.

In December he returned home to England on leave, arriving at Southampton just before the end of the month. The first news which greeted him on his arrival was that of the Tweefontein disaster, where De Wet had surprised a mixed force of Yeomanry and regulars in a night attack. Among the 50 killed in action was his friend Lieutenant Hardwick, Royal Field Artillery - or 'Little Pom-Pom' to Charles.

Newly engaged to Emily 'Bee' Beatrice Jones, daughter of Canon H. D. Jones of Chichester, Charles returned to South Africa in February 1902 and was seconded to Colonel Lowe's Staff, who were engaged in rounding up the Boers. He was duly promoted Captain and 'mentioned' (London Gazette 29 July 1902, refers), besides being awarded a well-deserved Distinguished Service Order, which was 'never better earned' according to his Commanding Officer.

Appointed Provost-Marshal to Lowe, for the conclusion of the war, he then took up post as Assistant Secretary to the Transvaal Repatriation Department. From 1902-06 he worked as Manager of the Transvaal Government Stud, a move which was certainly to the advantage of the farm and the stock. Even the pack of hounds which 'had been faring badly at the hands of their Zulu kennel keepers' now began to improve in condition.

In mid 1906, Bee began to suffer from ill health and Charles determined to return home, settling in Liverpool. He took work as Manager for The White's Carriage Company and became a member of the Liverpool Polo Club. Moving to Tyddyn, near Mold, North Wales, he set up his own equine business and spent days off hunting with the Flint and Denbigh Hounds.

Great War

Following the outbreak of the Great War, Charles applied to the War Office for service with a cavalry regiment. He was much perturbed, indeed 'moved with a fury of anger,' when, a few months later, whilst in command of 'C' Squadron, 5th Dragoon Guards, he received notice from a clerk stating that they had no need of his services.

He then tapped up to Lieutenant-Colonel G. Ansell, 5th Dragoon Guards - a cousin of Bee - requesting a job. Ansell duly replied, offering an 'office job', but soon thereafter, invited Charles to Beaumont Barracks, Aldershot, where under Ansell's tutelage his position was anomolous. At first, the men thought he was 'an interpreter, or war correspondent.'

Promoted Lieutenant, Charles landed at Havre on 16 August 1914, and engaged the Germans six days later on the Mons-Valenciennes Road. In regular contact during the retreat from Mons, Charles found himself a little too close for comfort in a wood held by French troops near the town of Le Cateau:

'I crawled to the edge of the wood as though I was deer-stalking. Just as I got near enough to get a look into the wood I saw, against the grey sky-line, a swarm of spiked helmets, and I can tell you I did not stay long.'

On another occasion, he calmly despatched a galloping Uhlan with his rifle:

'I held well forward and fired, to my intense surprise the horse and rider went head over heels like a rabbit well shot.'

The pennant from the Uhlan's lance was retained and proudly hung over the mantelpiece in the smoking-room at Tyddyn.

Heavily engaged at Solesmes and at Fuchy, the unit lost Ansell which proved a serious blow to Charles, for not only had he lost a friend, but he had lost his sponsor in the British Army. Fighting to the Aisne, he gained command of 'C' Squadron at the commencement of the First Battle of Ypres. On 13 March 1915, his men held a sector of the Ypres-Roulers railway during what Sir Herbert Plumer described as 'the heaviest bombardment yet experienced', the regiment being depleted by this time to approximately half strength.

It was on 13 May 1915 that he was severely wounded at Ypres. According to Lionel, 'he made so light of it that the majority in the regiment did not know he was touched.'

Nevertheless, the wound was a severe one and Charles was sent to England. He suffered great pain and had to undergo several operations, the result being the permanent disablement of his left shoulder which he would never use again. Mentioned in despatches (London Gazette 22 June 1915, refers) and appointed Brevet Major, 3 June 1916, Charles took a 'desk job' on the Headquarters Staff, Dublin, and was later promoted Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel, 1 January 1917, in recognition of his services during the Irish Rebellion. Further promotions followed, G.S.O.2., 25 January 1917, and G.S.O.1., 19 April 1918.

Whilst in Ireland, Charles also attempted to return to his old pursuit of hunting and it was noted that, having had his guns reconstructed to cater for the 'practically useless' left arm, he continued to shoot with great quickness and accuracy.

It was not just the Germans who had it in for Charles's left arm and shoulder. On a grouse shooting expedition, he had the misfortune to break his bad arm when a pony putting his foot through a rotten bridge led to him tumbling to the ground.

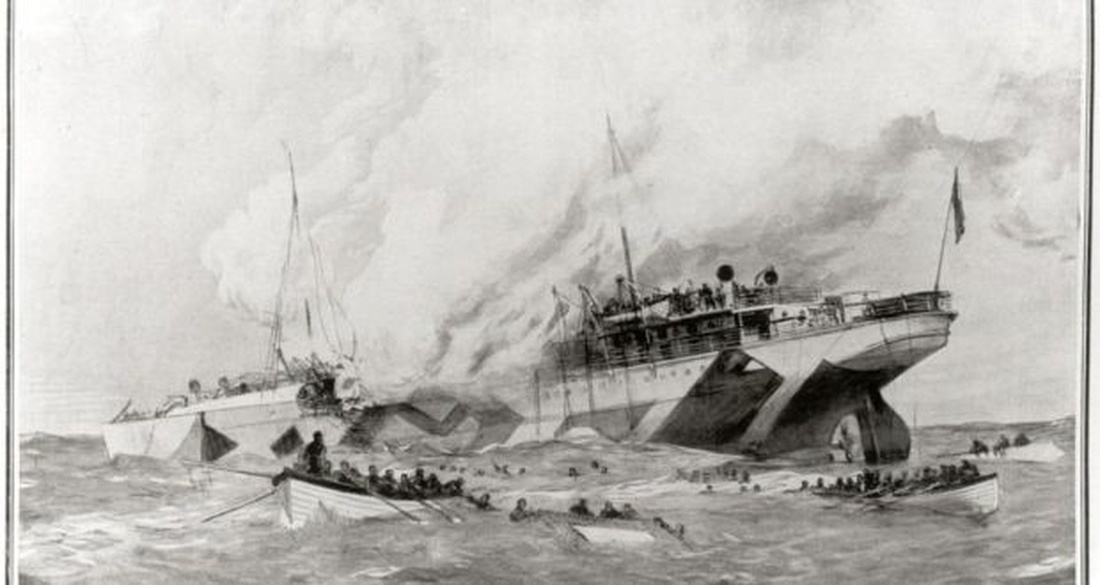

Journey's end - loss of R.M.S. Leinster

At the start of 1918 Charles clearly became anxious about his future. His business in Liverpool had suffered during the war and Tyddyn was sold. Keen to qualify for Staff work, for his disabled shoulder made regimental duties impossible, he help hopes for a permanent appointment after the war.

As a result, he applied for a Senior Staff course at Cambridge and on 10 October 1918 boarded the mail boat R.M.S. Leinster for passage from Dun Laoghaire to Holyhead, across the Irish Sea. Not knowing the fate that lay ahead, Charles was accompanied by his wife and two small children, Charles Bertram, born 3 September 1911, and Beatrice Audrey, born 24 June 1907.

At 09.40 a.m., in bad weather, the Leinster spotted a torpedo fired from U-123 which passed just in front of the bow, before a second struck. Having been ordered to about turn by Captain William Burch, a third torpedo struck the engine room, causing a vast explosion. Of the 77 crew and 694 passengers aboard, many of whom were soldiers returning from leave back to the Western Front, some 587 perished, including Charles, who would have stood little chance of survival given his disability. According to a poignant entry:

'The last seen of him was in the heavy sea, swimming as best as he could with his little girl Audrey on his back.'

Lionel wrote:

'You had a child in either hand as you went through The Valley of the Shadow, and, I doubt it not, you called to them bravely, cheerily, as they, with you, passed into The Unknown.'

Charles and both his children drowned. Amidst the chaos of deploying lifeboats in heavy seas, his wife somehow survived. His body - together with that of his son - was later recovered and a funeral service was held on 14 October 1918 in the Chapel of the Royal Hospital, Dublin, residence of the Commander-in-Chief, Irish Command. He is buried in the Royal Hospital Cemetery, Kilmainham; sold together with copied service record and a comprehensive file of research including a full copied account of Charles (Lieutenant-Colonel C. H. Blackburne, D.S.O., 5th Dragoon Guards), A Memoir, by Lionel E. Blackburne, with a foreword by Field-Marshal Viscount French.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£4,500

Starting price

£2400