Auction: 19002 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 228

A notable Great War M.C. group of five awarded to Major D. S. Spark, Somerset Light Infantry, later Military Pioneer Corps, a regimental character who penned a forthright account of the Battle of Cambrai, for the Scrap Book of the 7th Battalion

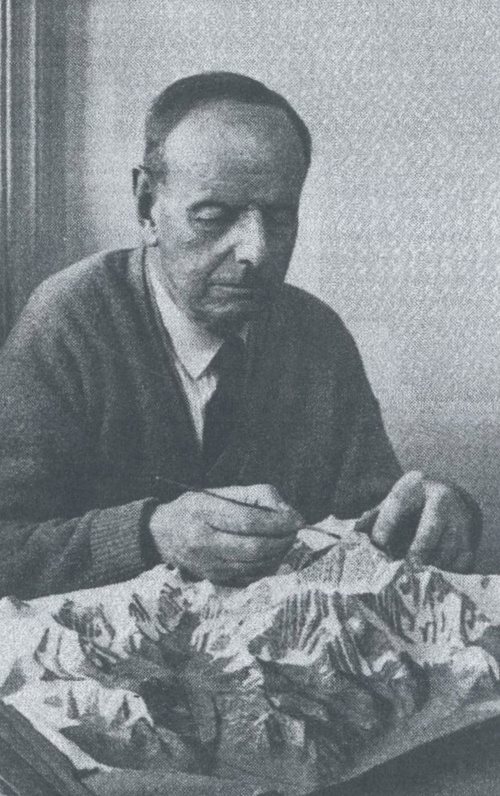

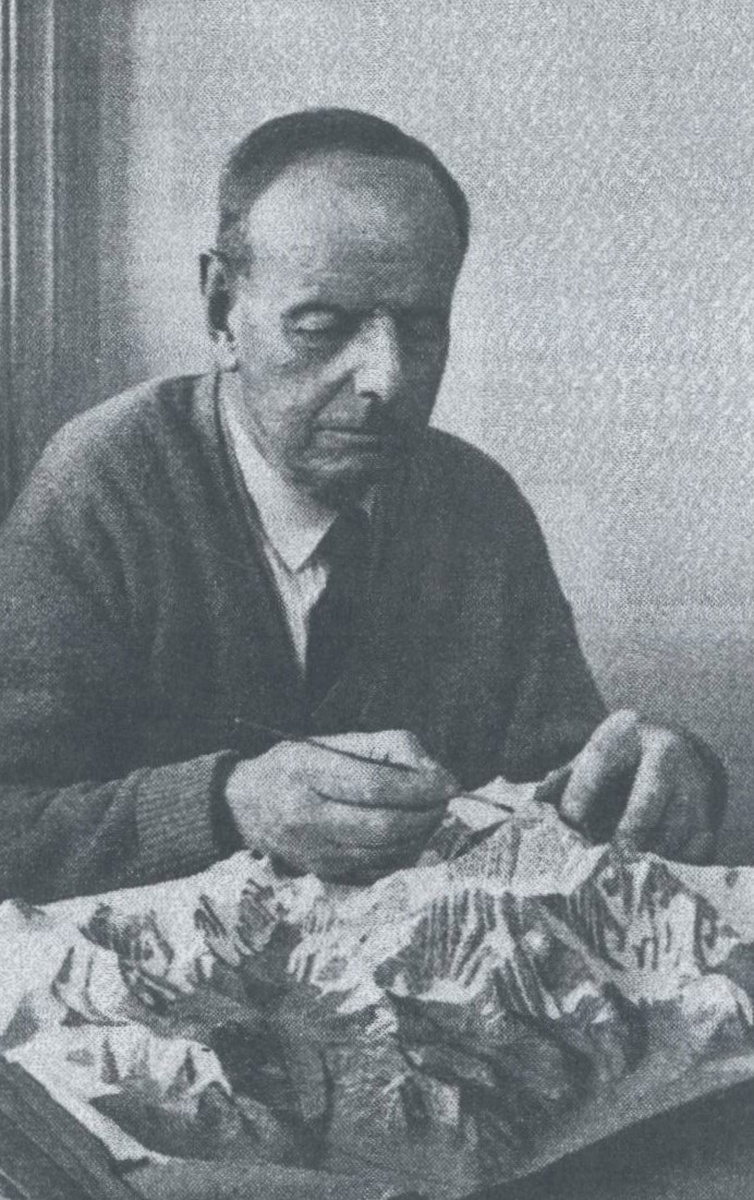

Spark latterly founded Ravenswood Prep School, returned to the fold during the Second World War and was a master scale-model maker

Military Cross, G.V.R., the reverse contemporarily engraved 'Awarded 2nd Lieut. D. S. Spark. Somerset Light Infantry. June 1st 1916.'; 1914-15 Star (2. Lieut. D. S. Spark. Som. L. I.); British War and Victory Medals (Capt. D. S. Spark.), Defence Medal 1939-45, BWM with officially re-impressed naming, otherwise good very fine (5)

M.C. London Gazette 1 June 1916.

Durbin Sanderson Spark was born 18 January 1893 at Ilkley, Yorkshire and educated at Repton and Emmanuel College, Cambridge. Commissioned 2nd Lieutenant on 16 August 1914, Spark served overseas with the 7th Battalion, Somerset Light Infantry from 24 July 1915. Serving on the Western Front, he would see the horrors of war first hand. Indeed, such were his experiences that his memoirs of February 1919 were revised in December 1931 to give an account of the Battle of Cambrai for Scrap Book of the 7th Battalion. That account is produced on pages 91-111, with Spark commenting on the days before battle:

'Having made all final preparations, we again went up to the front line on November 18th, armed with aeroplane photos, plans and maps and a strong conviction that now, at last, we were going to see a "real good show".

I had never been in a really big attack and from what I had seen and heard, had no wish to be. Many men looked forward to a "Push" as an escape from the stagnation of trench warfare, but I admit that I dreaded "going over the top". To me the idea of hand-to-hand fighting was worse than any amount of shelling. In addition, the possibility of being wounded and helpless in No Man's Land was a nightmare. In trench warfare one was tolerably certain of medical attention within a few hours, but I had seen (or rather heard) men taking days to die in No Man's Land and I still feel this was the worst fate a man could have.

But even I began to feel excited at the prospect of taking part in what we hoped would be the most sensational and bloodless battle in the whole war.'

Having moved to the front line in the early hours of 20 November, the 7th Battalion would be supported by a section of Tanks. He continues:

'At last, at five minutes before "Zero Hour" (6.50a.m.) we moved off behind the Tanks...Then we were out on the damp misty grass of No Man's Land. Suddenly with a deafening crash our guns opened the barrage. For a moment the enemy made no sign; then enquiring lights went climbing into the sky; they seemed to be trying to discover the meaning of this extraordinary affair! Behind these lights was an inferno of bursting shrapnel, brilliant high explosives and heavy clouds of smoke.

Now it was getting light, and Tanks, followed by small parties of infantry, could be seen on either side. Soon German shells began to scream and moan overhead, and looking back we saw them bursting on our own front-line which we had crossed only a moment before. Then I heard the rattle of machine-guns and the sinister noise of bullets whipping past. From this point everything seemed unreal to me. I felt no fear but only a vague curiosity. It all seemed impersonal and as if I were merely a spectator. I had no conscious thought, but little scenes impressed themselves upon my mind.

The next thing I remember was finding the Colonel [Troyte-Bullock] at my side; he shouted in my ear and I could just hear "Why don't the damned things go faster!" I think this is the only time I have heard him use a "big, big D". As he had a broad grin on and was obviously in high spirits, may it be forgiven him...

At last we were close to the German wire and the Tanks started to crash through it. It was at this moment that a company runner yelled at that Peard was wounded and I was to take command. I had been so fascinated by the scene around me and by the Tank's solemn and dignified progress that I had almost forgotten the men behind me...In the act of shouting to them to get their bayonets ready, I felt a strand of barbed wire catch me in the small of the back and slowly but steadily pull me forward. On turning, I was unable to get free and immediately saw that I should be pulled over the top of the Tank, which was pulling the wire over one of its treads. My orderly quickly borrowed some wire-cutters and cut the wire just before this happened!'

In the following days, Spark would have a number of exacting patrols in Masnieres, clearing houses of snipers and exploring and taking the underground passages and cellars which ran throughout the area. A large counter-attack forced the Somersets to their reserve trench some days later and they found themselves being raked with machine-gun fire and taking aim at low-flying enemy aircraft. Forming with the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry, 'C' Company came under attack from another machine-gun at close range:

'During this time three Germans with a light machine-gun came forward, planted the gun in the open about 400 yards from our trench and solemnly swept our parapet with fire. This went on for a few minutes and as no one seemed to be firing back at them, I and the D.C.L.I. officer began sniping at them between the bursts of fire.

After three shots he hit the gunner and knocked him over backwards; after two more shots, I hit the second man who had continued to fire the gun; the third man then picked up the gun and calmly walked back over the sky-line and out of sight. Those three were very brave men.

It is rather interesting to note that although I was in the trenches for about two years, the German I hit is the only German I am sure that I killed the whole time. I am sure that he was killed because we watched both the bodies later with field-glasses and neither moved at all.'

Having been in the line for two weeks under constant pressure, Spark was finally withdrawn:

'I was too tired to talk, and after a meal, only remember saying something about going to see about the men's food. We lay down and fell asleep immediately, unwashed, with beards and in our clothes. I just remember Chappell say; "Come on Berry, let's go and see that those poor devils get plenty of rum."'

His account closes:

'Though I hated the war intensely, I hope I have indicated my respect and admiration for my brother officer, my pride in my own Company and my very real attachment to the Somerset Light Infantry.'

Released from service, he founded the Ravenswood Preparatory School at Tiverton with his wife, which grew into a great success. Started as a 'Preparatory for the Public Schools and Royal Navy', it remains to this day. Spark was recalled with the Military Pioneer Corps during the Second World War. Besides his teaching, he was a keen scale-model maker of some note, for Sir John Hunt and the Royal Geographical Society were amongst those who commissioned models of mountains.

Upon his death at Exmouth, Devon on 30 December 1964 The Light Bob Gazette stated:

'Spark was a moving spirit, very loyal and never failed to be present at the annual dinner, academically minded and loquacious, he approached all orders with caution wanting to know the whys and wherefores.

In tight corners one would have been happy if either had been alongside and even now, after fifty years one can see Spark at Lillebeke with a petrol can half full of hot tea, struggling through squelching mud to take some warm comfort to his forward platoons.'

Sold with an original copy of Scrap Book of the 7th Battalion, with the foreword by Lieutenant-Colonel Troyte-Bullock. For his awards, please see Lot 225.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£1,500

Starting price

£550