Auction: 19002 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 103

'His greatest achievement lay in his creation of a small native army, which, under English officers and Sikh non-commissioned officers, has proved such a potent arm for the defence of the new protectorate against Arab and Zulu aggressors. In this force slavers and former slaves were enrolled and have since fought with unwavering courage and loyalty in the cause of the establishment of law and order in South Central Africa.

Africans, however, do not usually shed their blood for a cause, but rather as the followers of a leader in whom they believe, whether that leader be a slave-raiding Arab or a servant of the Queen. Edwards had a remarkable personal attraction - almost magnetic - for these grown-up children, and his influence over them was quite exceptional, and can ill be spared at the present juncture, even though he leaves an able successor of nearly the same length of service as himself, Captain W. H. Manning.'

So states The Times obituary notice of May 1897 for Lieutenant-Colonel C. A. Edwards, Indian Army.

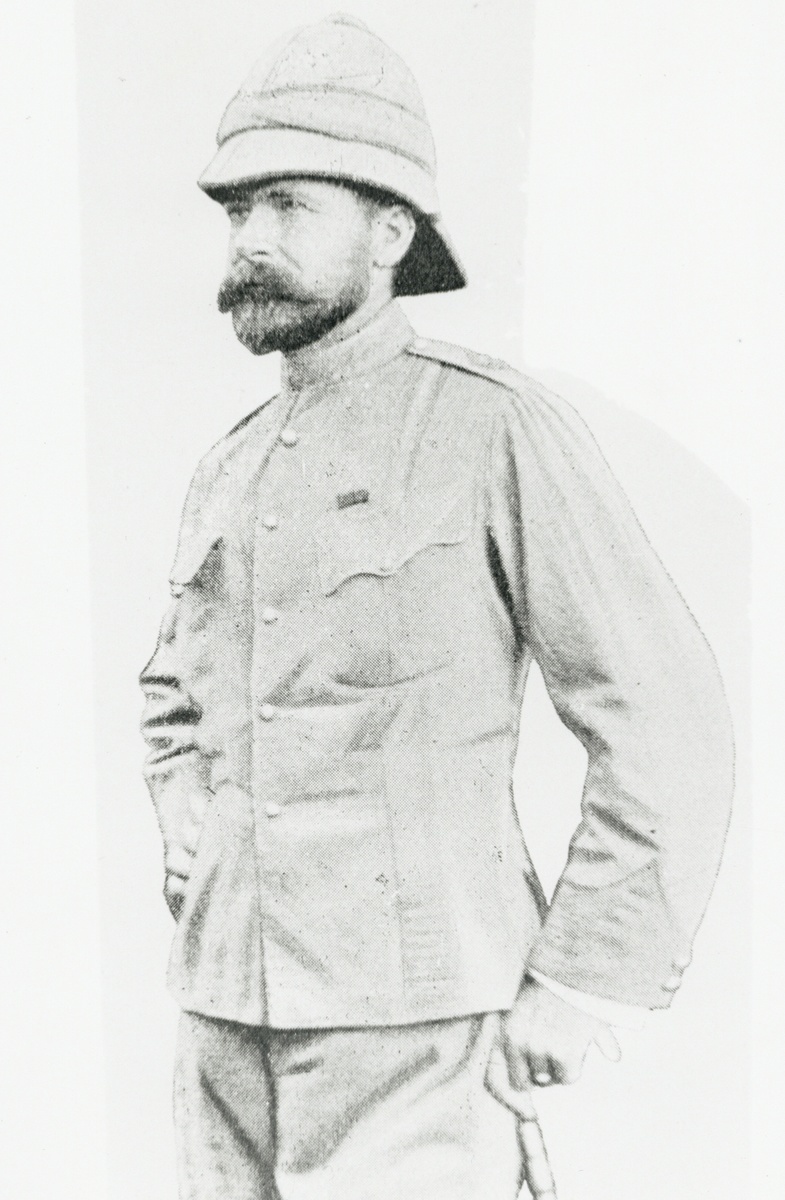

The important Burma and Central Africa campaign pair awarded to Lieutenant-Colonel C. A. Edwards, Indian Army, late Royal Welsh Fusiliers

Such was the scale of his achievements in anti-slavery operations in 1893-97 - at the head of his beloved Sikhs and ultimately as Commandant of Armed Forces in British Central Africa - that Edwards gained advancement from Lieutenant to Lieutenant-Colonel in just six months

Repeatedly the recipient of direct commendations from Her Majesty's Secretaries of State for Foreign Affairs, he was recommended for a C.B. in the period leading up to his untimely demise from fever at Tomba in May 1897, aged just 33

It has been said that Edwards's gallant command of a string of successful campaigns put pay to slave-raiding and slave-trading - even the very status of slavery - in a vast expanse of territory extending from the Lower Shire to Lake Tanganyika: certainly his name ranks high on the list of those who gave their lives in the 'Scramble for Africa', for but a handful of such men achieved such spectacular success in such a short space of time

India General Service 1854-95, 1 clasp, Burma 1885-7 (Lieutt. C. A. Edwards, 1st Bn. R.W. Fus.); Central Africa 1891-98, 1 clasp, Central Africa 1894-98 (Major C. A. Edwards, 35th Bl. Infy.), the last with official corrections, otherwise good very fine (2)

Charles Augustus Edwards was born in London on 25 February 1864 and 'came from a family of Welsh extraction, which had contributed several of its members to the Army and Indian Civil Service'; his Times obituary notice, refers.

First commissioned as a Lieutenant in the King's Own Scottish Borderers in May 1885, he transferred in the following month to the Royal Welsh Fusiliers and proceeded to India, where he served in the campaign in Burma 1886-87 (Medal & clasp).

Having then been appointed to the Bengal Staff Corps in October 1887, Edwards was posted as a Wing Officer to the 35th Sikhs in September of the following year. According to The Times, he then came to the attention of the C.-in-C. India and was selected as second-in-command of the Sikh Contingent for service in British Central Africa in 1892.

British Central Africa 1893-97

Much has been written about Edwards's significant part in expanding British interests in the region, the whole conducted under the watchful eye of Sir Henry 'Harry' Johnston, G.C.M.G., K.C.B., the famous explorer and administrator. Sir Harry was acting as Commissioner at the time of Edwards's exploits and, in July 1896, put the latter's name forward for advancement to Lieutenant-Colonel and a Companionship of the Order of the Bath (C.B.), Military.

In putting his recommendation before the Marquess of Salisbury, Sir Harry stated:

'Major C. A. Edwards was specially selected by his Excellency the Commander-in-Chief in India for service in British Central Africa at the beginning of 1893 with the new Sikh contingent then proceeding to the Protectorate.

When Captain (now Major) C. E. Johnson was wounded in July 1893, Major Edwards carried out alone a successful campaign against the Yao Chief, Nyaserera, who had attacked Major Johnson, capturing his strongholds and compelling him to come in and sue for peace, for which services he received your Lordship's predecessor in office.

In October 1893, Major Edwards took a prominent part in the campaign against Mkanda, in the Mlanje district, which was also brought to a satisfactory conclusion.

In the late autumn of the same year Major Edwards fought with distinction at Chiwaura's (west coast of Lake Nyasa) and at Makanjira's (east coast of Lake Nyasa). He built Fort Maguire on the site of Makanjira's town and in January 1894 repelled an attack on the fort by over 2,000 well-armed Yaos under Makanjira, with a loss to the enemy of forty-five killed, many wounded, and a number of prisoners.

In the autumn of 1894, Major Edwards was sent by Acting Commissioner Sharpe to intervene in the affairs of the Angoni-Talus, on the west aide of Nyasa, who were harassing the country with their internecine wars. His negotiations were so successful that ever since there has been peace amongst the Angoni. They have ceased to raid the British Protectorate and have sent large numbers of labourers to the Shire Highlands coffee plantations.

Early in 1895, Major Edwards joined me in India and assisted me to raise the last Sikh contingent, now serving in British Central Africa. He was permitted by the Commander-in-Chief to engage for another period of service in Africa and returned with me as Commandant of the Armed Forces of the British Central Africa Protectorate, a position he has occupied since April 1894. Upon returning to Africa in May 1895, Major Edwards proceeded to organize a native contingent largely composed of the troublesome restless Yaos who had been fighting us for four years. These men he placed under Sikh drill instructors, and the steady, courageous way in which they have fought during the autumn campaign that followed amply justified his confidence in their rapid conversion from foeman to friend.

In the autumn of 1895, Major Edwards took a leading part in the wars with Matipwiri, Zarafi, Mponda, Makanjira and the North Nyasa Arabs. These actions have already been sufficiently described to your Lordship, who has directed me on more than one occasion to express to Major Edwards your Lordship's special approval of his actions.

I might further add that, owing to Major Edwards's influence among the natives of Nyasaland, and his organization of the native contingent, we have been able to dispense entirely with the Makua soldiers hitherto brought from Mozambique. Major Edwards returns shortly to British Central Africa for a third time.'

The above operations - and those fought in the autumn of 1895 - are described at length in R. C. F. Manghan's Africa As I Have Known It. But for the purposes of a more immediate summary, the following extract is quoted from W. D. Gale's Zambezi Sunrise:

'The original contingent of Indian soldiers who had given valiant service returned to their homeland at the end of their three-year period and were replaced during 1893 by two hundred Sikhs. At the same time the Zanzibaris who had formed part of the police force were disbanded and replaced by Atonga from West Nyasa and Makua tribesmen from Portuguese East Africa. As time went on Johnston recruited more and more natives from the recognized fighting tribes as these became pacified to assist him preserve law and order.

The main trouble spot during 1893 was Kota Kota, on the western shore of Lake Nyasa, which was a sultanate originally established by the Sultan of Zanzibar and ruled by an independent potentate called the Jumbe. Puffed up by his victory over Captain Maguire, which because of his preoccupation with more urgent matters in other parts of the Protectorate Johnston had had to leave unavenged, the troublesome Makanjira attacked the Jumbe, who was friendly to the British, and by the middle of 1893 had captured most of his territory until the Jumbe was penned in Kota Kota itself. He was having difficulty holding out, and since the gunboats were now ready Johnston decided that the time had come to settle accounts.

The first step was to relieve the Jumbe, who was now being besieged by one of his Yao headmen who had gone over to the enemy. The Yao's fortified town, five miles from the lake shore, was bombarded and taken by storm and the headman himself was killed. The expedition then crossed the Lake and meted out similar treatment to Makanjira's town and a number of smaller towns and villages, including the village where Maguire, Boyce and MacEwan had met their deaths. Fort Maguire was erected on the Lake shore and garrisoned by Sikhs. Early in 1894 Makanjira attacked the fort but was defeated with heavy loss. His power at last was broken and he sought refuge in Portuguese territory.

The year 1895 saw success crown Johnston's grim, tenacious efforts to teach the slavers the error of their ways and win them over to the Administration. Matipwiri was an Arabised Yao who held the pleasant, well-watered country to the east of Mlanje and the Ruo river commanding the route from Lake Nyasa to Quilimane. He had grown rich by taking toll of the ivory exported to the coast and of the goods brought into Nyasaland, an African robber baron. When he heard that Matipwiri was planning to attack Fort Lister on Mlanje and the scattered European settlement in the vicinity of the mountain, Johnston took action against him in September, and Matipwiri surrendered unconditionally.

Another chief who had to be brought to book was Zarafi who dominated the territory to the east of the Upper Shirè and had long been an active slaver. Johnston set out with a force consisting of 65 Sikhs and 230 native soldiers commanded by Major C. A. Edwards. Their objective was Zarafi's capital on Mangoche Mountain, entailing a march of 78 miles from Zomba of which 50 were through enemy country. Porters were provided by friendly chiefs of the Mlanje district. Their conduct was admirable. Although repeatedly under fire they never once abandoned their loads or attempted to run away.

Mangoche Mountain was a great ridge about twelve miles long and a mile broad and rose to 5,500 feet at its highest point. It was difficult country, ideal for ambush, but two guides provided by a rival chief, Kawinga, led the force by a little known route to within fifteen miles of Zarafi's town. The first attack came when they entered a wooded gorge leading up to the south-eastern base of the mountain, and the fire was directed chiefly against the porters. The fire was wild and none of the porters was hit but an Atonga soldier was wounded. A charge by the Atongas, led by Major Bradshaw and Captain Cavendish, scattered the enemy before they could reload.

Shortly afterwards the force reached a natural castle of rocks crowning a hill which dominated the route. Zarafi had expected them to come from another direction, and the castle was unoccupied. As soon as he discovered his error he sent a large body of men to defend the hill. Not knowing that the police had already arrived they advanced openly and suffered many casualties. The porters rested at this spot while Major Edwards and the majority of his force pushed on for three miles along the ridge. The terrain was all in the enemy's favour - steep hillsides and enormous boulders from behind which Zarafi's men poured a galling fire on the soldiers toiling up the narrow path. Casualties, however, were few because most of the natives aimed too high and the damage was done by a few good marksmen armed with Snider rifles. The officers with the force who were armed with Lee-Metford rifles did great execution and killed about thirty-five of the enemy, whose total losses before the day's fighting ended was more than a hundred men. As a result of this encounter the police seized another favourable position for the final assault on Zarafi's stronghold, but the enemy gave them no rest. Snipers got busy and both Johnston and Major Edwards had narrow escapes, but the 7-pounder was brought into action and cleared the hillsides.

Before dawn the next morning (October 28, 1895) the police climbed Mangoche Mountain without losing a single man. The enemy was completely routed and Zarafi's town was captured without difficulty. Zarafi had already fled, having taken the precaution of sending his ivory, cattle, most of his women and his reserve gunpowder to a Yao chief in Portuguese territory for safe keeping. Only a few slaves were found in the town, and Johnston was disappointed to learn that a large number of slaves had been sold to caravans bound for the coast a few days before. There was very little loot, but one item which pleased Johnston greatly was a 7-pounder gun which Zarafi had captured from a small force sent against him three years previously, one of the few defeats suffered by his police in six years of almost incessant campaigning. The gun was a welcome addition to his armament.

Johnston was impressed by the beauty of the country occupied by Zarafi. "It is marvellously well watered by countless streams and is very fertile in between the mighty boulders with which it is strewn," he wrote. "Zarafi's town enjoys about the most remarkable situation of any place in the Protectorate, being sited on a flat ridge about a quarter of a mile broad at an altitude of 4,250 feet. It is the most practicable gateway into Nyasaland from the East Coast. From the town you can see on the one hand right down the valley of the lower Lujenda for a tremendous distance towards the East Coast; you can see along the marshy lake of Chiuta; from another point you can see the Zomba and Chikala Mountains, the whole course of the Upper Shirè from near Mpimbi to Lake Malombe, then the whole length of the Malombe to the extreme Upper Shirè and the south-eastern gulf of Lake Nyasa up to Cape Maclear, besides gazing westwards to the great tablelands of the Angoni." A truly remarkable view.

The bulk of Zarafi's people were of Anyanja stock who had been dominated by the Yaos. Now that most of the Yaos had fled with Zarafi to their original homeland beyond the Portuguese border, the local people returned and settled down quietly in their old homes. The power of another Yao tyrant had been broken.

The north end of Lake Nyasa, which had been the scene of so much bitter fighting between the African Lakes Corporation on the one side and the Arab half-caste, Mlozi, and his Awemba allies on the other, had been reasonably tranquil following Johnston's arrival in 1889 when Mlozi had signed a treaty promising to keep the peace and at Johnston's request had destroyed an Arab fort, known as Mselemu's stockade, which had commanded the Stevenson road to Lake Tanganyika. But towards the end of 1894 the trouble flared up again. Two large villages which provided porters for the African Lakes Corporation's traffic on the Tanganyika road were attacked by the Arab slave traders and the Awemba, and the occupants were almost entirely exterminated. They also blocked the road with tree trunks and began rebuilding Mselemu's stockade in open defiance of the 1889 treaty.

The unrest in the area affected the adjacent German territory of Tanganyika and the German commandant placed a steamer at Johnston's disposal to help him deal with the insurgents. The missionaries and the agents of the African Lakes Corporation, fearing attacks on their stations, urged the Commissioner to take immediate action to end the trouble, and the trusty little Domira was again employed as a troopship.

The North Nyasa Arabs had overreached themselves. They were up against an entirely different adversary now. Six years before they had had to contend with gallant amateurs assisted by unreliable native allies, all of them inadequately armed. Now they found themselves attacked by disciplined troops, capably led by professional officers and armed with modern weapons. The attack on the Arab forces was launched on December 1, 1894, and after two and a half days' fighting was completely successful. All the stockades were taken and destroyed. The principal culprit, Mlozi, was captured, tried for his crimes, found guilty and executed. During the fighting in and around Mlozi's stockade, the Arabs lost more than two hundred men, against Johnston's losses of one European officer severely wounded, one Indian and three native soldiers killed and six Indian and four native soldiers wounded. They released 569 slaves. The Arabs had intended to make a big stand at Mlozi's and had turned the town into a powder magazine. Early in the fighting the house in which the gunpowder was stored was hit by a shell, with satisfactory results.

Johnston has given an interesting description of Mlozi's town as typifying the stockade erected by the leading slavers. It covered an area of just over twenty acres and was surrounded by walls in which there were five gateways. The outer wall, eight feet high, was made of logs planted firmly in the ground and almost touching, wattled with strong twigs and plastered inside and out with mud until the total thickness of the wall was about two feet. Parallel with the outer wall and about twelve feet away from it was another similar wall seven feet high. The space between them formed a gallery which was roofed over and divided into partitions by wattle and mud walls every twelve feet. The roof was made of two layers of logs on which grass was spread and then two feet of mud well beaten down. The total circumference of the walls was 1,160 yards.

Both the inner and outer walls were loopholed in two rows, one at four feet and the other at eighteen inches from the ground. In the partition walls which divided the gallery between the two walls into rooms were small doorways and every third or fourth room had an additional doorway leading into the town. In each room were two trenches about three feet deep close to each wall and the earth taken from them was piled up in the centre of the room. There were about 260 of these rooms and Mlozi's fighting men lived in them. Such a defence work was impregnable to attack by ordinary native weapons and the smaller European arms. Solid shells were not very effective, either. It took incendiaries and high explosives to reduce Mlozi's stronghold to ashes.

One last wrong remained to be righted - the treacherous murder of Boyce and MacEwan during Captain Maguire's ill-fated attack on Makanjira's dhows. Makanjira himself had been driven out of Nyasaland, but there remained the man primarily responsible for the treachery that had led to their deaths, Makanjira's lieutenant, Saidi Mwazungu. After the final overthrow of Makanjira he had sought refuge with the notorious Angoni slaver, Mwasi Kazungu, in the Marimba district. Many of Makanjira's fighting men had joined Saidi and he had built a strong stockade in Kazungu's country. With a loyalty typical of the Arab slave trader, Saidi was conspiring with Angoni chiefs to the north and south and with the Mohammedans at Kota Kota to take control of his benefactor's territory, after which he proposed to attack Kota Kota, where the Jumbe was friendly to the British, and drive the garrison into the Lake.

Johnston soon spoilt this little plan. He sent a strong force in December, 1895, and after some severe fighting the conspirator's forces were routed. Saidi Mwazungu was captured and the foul crime committed five years before was avenged.

In a letter to Lord Salisbury dated January 24, 1896, Commissioner Harry Johnston was able to report that as a result of his actions 'there does not exist a single independent avowedly slave trading chief within the British Central African Protectorate, nor anyone who is known to be inimical to British rule. Those enemies whom we have conquered, like all with whom we have fought since our assumption of the Protectorate, were not natives of the country fighting for their independence but aliens of Arab, Yao or Zulu race who were contesting with us for the supremacy over the natives of Nyasaland.'

The traffic in human flesh and blood was ended.'

Thanks largely to Edwards and his beloved Sikhs. Job done.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£9,500

Starting price

£2100