Auction: 19001 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 367

(x) The Property of a Gentleman

A FINE COLLECTION OF AWARDS TO OFFICERS OF THE CRIMEAN WAR

Cataloguer's Note

The Crimea Medal certainly divides opinion. Its distinctive oak-leaf clasps and floriated suspender are an acquired taste, viewed by many as overly embellished and 'heavy'. It was ever thus, and I couldn't resist quoting the reaction of Colonel Hodge, 4th Dragoon Guards, on receiving his Crimea Medal in September 1855:

'A vulgar looking thing, with clasps like gin labels. How odd it is that we cannot do things like people of taste.'

Coming after the austere Neo-classicism of the Military and Naval General Service Medals, the Crimea Medal must have seemed bewilderingly garish to those who received it. In artistic terms, it arrived at the height of the Gothic Revival, when the medieval fantasies of Pugin, Barry and the Pre-Raphaelites infiltrated every art form, from architecture to jewellery. This surely accounts for its radical design, the oak leaves resembling carved wood on a Gothic misericord.

The Crimea Medal was radical in another sense. Previous campaign medals had been awarded retrospectively, long after the conclusion of hostilities. The Crimea Medal was the first to be issued in the theatre of operations, during the campaign itself. This gave it added poignancy, and despite all the problems it has caused medal collectors ever since (see 'By Order of Her Majesty' - The Crimea Medal, OMRS, 2017), it is those period photographs of fearsome-looking Guardsmen and Highlanders, proudly wearing their Crimea Medals, which stir our imagination. We think of the legendary actions for which those men were decorated: the storming of the Great Redoubt at the Alma, the Thin Red Line at Balaklava, the Sandbag Battery at Inkermann, the capture of the Quarries before Sebastopol. The Crimea Medal's proximity to those actions is its enduring appeal.

The men whose medals form this outstanding collection were prominent in all of those engagements, and in many cases they shaped the course of events. Would the Great Redoubt have been taken if Major Champion (Lot 370) had not brought up the 95th Foot in support? Would Scarlett and the Heavy Brigade have been surrounded if Major Burton (Lot 372) had not intervened? Might the British have suffered fewer casualties at Inkermann if Major Armstrong (Lot 375) had not directed the Guards Brigade towards the Sandbag Battery? The enormous influence these men exerted is matched only by their supreme personal courage, often shown in adversity and against overwhelming odds.

In describing these remarkable men, I feel I have barely scratched the surface; whoever becomes the custodian of these medals can look forward to years of new discoveries.

Jack West-Sherring

Spink, February 2019

The intriguing 'Alma casualty's' group of three awarded to Lieutenant-Colonel Sir John Dugdale Astley, 3rd Baronet of Everleigh, Scots Fusilier Guards; while leading his Company up the Alma's southern bank under galling enemy fire, his men fell victim to a spirited Russian counter-attack on the Great Redoubt.

As the panic-stricken 23rd Foot crashed into his Company, Astley's steady presence averted disaster; just as he was rallying his men, a Russian musket ball passed clean through his neck, missing his carotid artery by a hair.

Popular among soldiers and sportsmen alike, Astley's colourful personality earned him the nickname 'The Mate'. His memoirs, Fifty Years of My Life (1894), contain a panoply of Victorian sporting pursuits. A close friend of Gerald Goodlake V.C., he remained part of the Regimental family until his dying day.

Crimea 1854-56, 2 clasps, Alma, Sebastopol (Major Astley, S. F. Gds. Septr. 1855.), naming officially engraved by Hunt & Roskell in serif capitals, date contemporarily engraved in running script, unofficial rivets between clasps, fitted with a Hunt & Roskell silver top riband buckle of which the pin is gold; Turkey, Ottoman Empire, Order of the Medjidie, 4th Class breast Badge, silver, gold centre and enamel, fitted with a silver top riband buckle; Turkish Crimea, Sardinian issue, privately manufactured by Hunt & Roskell, fitted with a Hunt & Roskell silver top riband buckle, the first with suspension claw re-affixed, nearly very fine, the remainder good very fine (3)

Provenance:

DNW, October 1993.

Order of the Medjidie London Gazette 2 March 1858.

John Dugdale Astley was born in Rome on 19 February 1828, eldest son of Sir Francis Dugdale Astley, 2nd Baronet (created 1821) of Everleigh, near Marlborough, and Emma Dorothea Lethbridge. Among his ancestors were Thomas de Astley, slain at Evesham in 1265, and Jacob Astley, 1st Baron Astley, who commanded the Royalist infantry at Edgehill, Naseby and Stow-on-the-Wold.

Educated at Eton, Astley attended Christ Church College, Oxford from October 1846. A stalwart member of the Bullingdon Club, he ran up gambling debts of over £400. His equestrian skills now came to the fore: hiring a racehorse named Ochre, he rode magnificently in steeplechases and used the prize money to pay off creditors. He was also an excellent shot, claiming he 'took to shooting like a duck to water' (Astley 1894, 22), the first recorded use of this expression in the English language. Gaining a reputation as a loveable tearaway, he shirked lectures and broke numerous College rules, paying another student called Boddington to translate his prescribed Greek texts at the rate of two shillings per 100 lines (Astley 1894, 38). After four months he was 'sent down'.

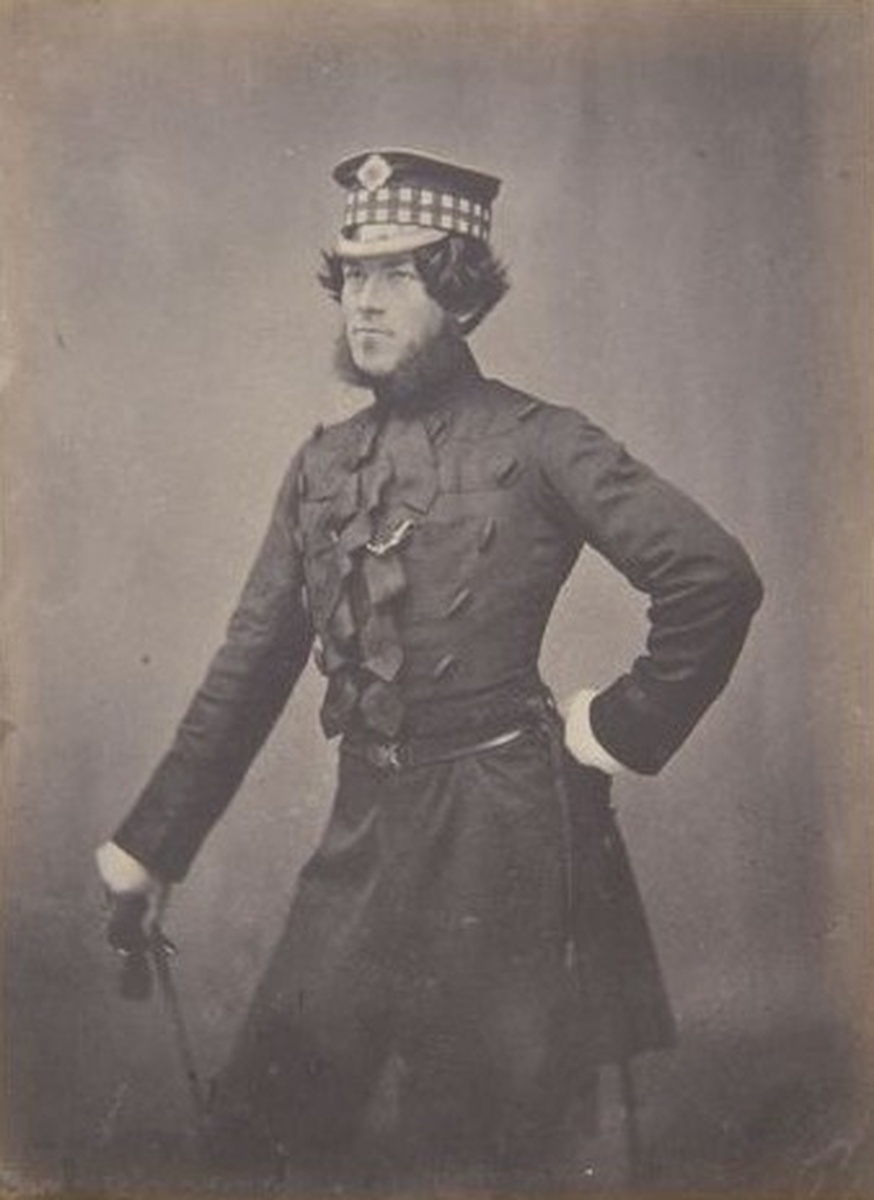

Astley then enjoyed a long sojourn in Switzerland, staying with local people in chalets around Lake Geneva. In his entertaining memoirs, Fifty Years of My Life (1894), Astley described this period as 'the pleasantest of my life'. It was cut short in February 1848, when he received news that he would soon be gazetted as an Ensign to the Scots Fusilier Guards (London Gazette, 31 March 1848). With great reluctance he returned home, joining his Battalion at Portman Street Barracks just in time for the Chartist Riots. Promoted to Lieutenant on 18 April 1851, he was in the guard of honour that watched over the Duke of Wellington's body as it lay in state at the Royal Hospital Chelsea on 13 November 1852. During the funeral procession his Battalion lined Fleet Street and Ludgate Hill.

A famous sportsman, Astley took part in numerous much-publicised foot-races at Windsor Home Park in late 1853, in the full presence of the Court. His most formidable opponent was Lieutenant Frederick Sayer, Royal Welch Fusiliers (see next Lot). Sayer beat Astley in the 150 yard sprint over flat ground, but honour was restored in the 150 yard sprint over hurdles, when Sayer 'took off wildly, overjumped himself and all but came down, losing so much ground that he could never recover it' (Astley 1894, 170). Regimental pride was at stake, and large sums of money had been wagered on the event. Astley and Sayer were friends for life.

'Eastward Ho!'

After a fortnight's leave at Everleigh, the family seat, Astley was assigned to Captain Hepburn's No. 5 Company, the "Fighting Fifth", 1st Battalion, Scots Fusilier Guards. The Battalion was to form part of Bentinck's Guards Brigade in the Duke of Cambridge's 1st Division. It paraded at Wellington Barracks on 28 February, receiving an emotional farewell from Queen Victoria as it passed Buckingham Palace with the Band playing "The Girl I Left Behind Me" (Astley 1894, 178). Her Majesty made no secret of the fact that the Scots Fusilier Guards were her 'favourites'. The Battalion then marched down the Strand to Waterloo Station, cheered by enormous crowds. Astley recalled the scene:

'There were very many touching episodes of heart-rending grief as we drew near the station-gates, where only the soldiers were admitted, and at one time it seemed almost impossible to shake off some of the poor women who broke into the ranks and would cling to their loved ones. Liquor, of course flowed very freely, and there was hardly a man who had not several flasks stuffed into his uniform, let alone his bearskin cap.'

Entraining to Portsmouth, the Battalion embarked on 'a horrible, half-rotten old steam transport, called the Simoon', which reached Gibraltar on 12 March. Britain and France formally declared war on Russia on 28 March, after she had failed to evacuate her troops from the Danubian principalities. The Battalion landed at Scutari on 27 April. On 24 May the British troops held athletic games in celebration of Queen Victoria's birthday. In a bizarre ritual evoking Homer's Iliad, the troops danced around a 40-foot wooden obelisk. With all his ancestor's royalist fervour, Astley climbed to the top and called for three cheers for Her Majesty the Queen (Astley 1894, 188).

On 14 June the Battalion encamped at Varna, where diarrhoea, cholera and dysentery took hold. Embarking on the Kangaroo on 28 August, it crossed the Black Sea and was nearly lost in a collision with the steamer Hydaspes. It landed on the coast of Eupatoria, seventy miles north of Sebastopol, on 14 September. Astley kept a diary at the time, commenting: 'At last this is more like business and all are in the highest spirits.'

The Alma - 'The most exciting day of my life'

At 11 a.m. on 20 September, the Allied forces advanced towards the southern bank of the River Alma, crowned with formidable Russian batteries. These positions had to be taken if the march on Sebastopol was to continue. Sir George Brown's Light Division was first into the fray, fording the Alma and scaling the steep enemy bank as shot and shell rained down. Despite terrible casualties it succeeded in capturing the main objective, the Great Redoubt. The 1st Division was too far behind to offer immediate support, the Duke of Cambridge insisting on forming up properly on the southern bank rather than charging headlong as the Light Division had done. Meanwhile, up on the Great Redoubt the Russian Vladimir Regiment counter-attacked, driving the Light Division back from their hard-won gains.

Colonel Sir Charles Hamilton of the Scots Fusilier Guards could not ignore the Light Division's plight. Disobeying Cambridge's order, he turned to his men and cried: "advance and support the Light Division." The Regiment charged up the slope with little semblance of order. One of the Light Division's Regiments, the 23rd Foot (Royal Welch Fusiliers), had suffered terribly in the Russian counter-attack, and a staff officer gave the order: "Fusiliers - Retire!" Since the Scots Guards at that time bore the title 'Fusiliers', the order was believed to refer to them. Confusion spread through both regiments as buglers sounded the 'Retire', the knotted masses forming perfect targets for Russian grape and canister. Meanwhile the 1st Coldstream and 3rd Grenadiers, which had advanced on either side of the Scots as steadily as if on Horse Guards Parade, chorused gleefully: "Look at the Queen's Favourites now!"

No. 5 Company formed the exact centre of the Scots Fusilier Guards' line, and was thrown into such disarray as the 23rd's panic-stricken remnants careered into it that many Guardsmen were sent tumbling down the hill, breaking necks and limbs. Astley tried desperately to rally his men, his steady presence - derived partly from his bull-like physique - keeping many wavering Guardsmen in check and preventing a complete rout. Just when he had restored order, Astley received a musket ball clean through the neck, narrowly missing his carotid artery. Dazed, he staggered back to the river and collapsed on the northern bank, where a drummer offered him brandy. He was just conscious for long enough to see the Guards storming the Great Redoubt. His Company had lost every officer wounded, with 38 casualties among the rank and file.

As the British Army lacked a medical transport system, Astley was eventually carried to the hospital ship Sanspareil by sailors using a strip of canvas between two oars (Astley 1894, 220). He then transferred to the Colombo, bound for Scutari, with 800 other casualties of whom 50 died during the voyage. On 19 October the doctors ordered him home. He arrived at Dover aboard the Veotis on 19 November, and was soon back at Everleigh.

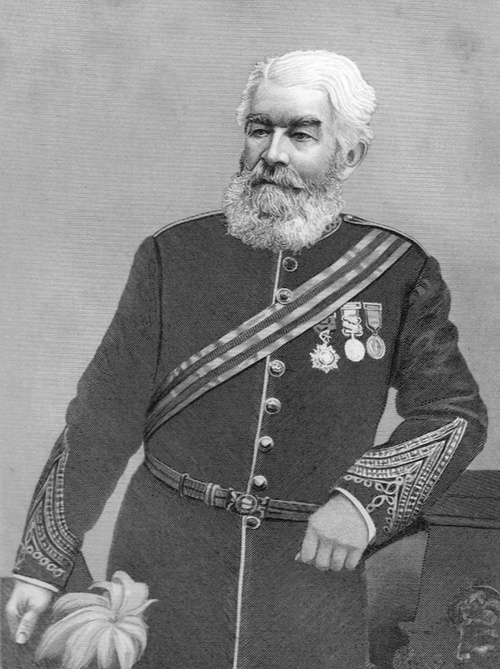

Astley returned to the Crimea the following year, arriving in Balaklava Harbour on 2 May 1855. Assigned to his old Company, he was frequently under fire while on trench duty before the walls of Sebastopol. Breveted Major, he was put in charge of the Brigade Hospitals at Balaklava, where he formed a close bond with Gerald Goodlake V.C., Coldstream Guards. 1st Division was held in reserve during the final assault on the Redan on 8 September. On 20 September, the Anniversary of the Battle of the Alma, Astley was awarded his Crimea Medal in a presentation by Lord Rokeby at Balaklava (Astley 1894, 276). His award of the Order of the Medjidie, 5th Class was gazetted on 2 March 1858. He always wore the larger breast Badge of the 4th Class, as is evident from his portrait aged 66 (see below).

'The Mate'

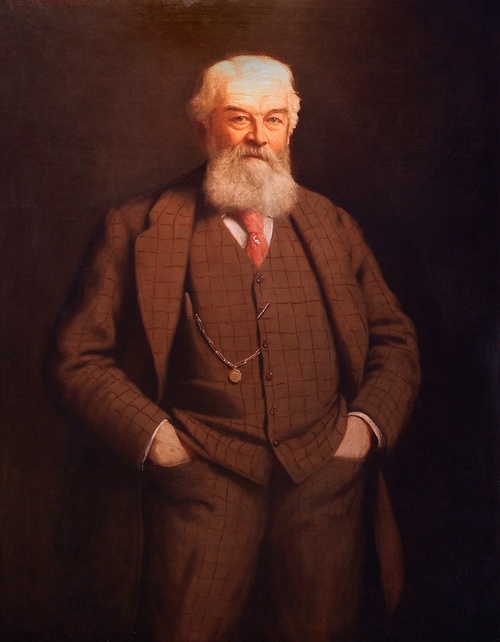

Astley married Eleanor Corbett, only daughter of Thomas George Corbett, of Elsham Hall, Lincolnshire, at St. James's Church, Elsham on 22 May 1858. Gerald Goodlake V.C. was his best man. He then retired from the Army, having reached the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. Devoting himself to sport, he became a prominent figure among Newmarket's racing personalities. His addiction to gambling resurfaced, and he alternated between extremes of comparative wealth and poverty. He nevertheless used his considerable influence to help others, particularly young jockeys, and he established the careers of George Fordham and Charlie Wood. His warm personality, coupled with his sailor-like beard, earned him the nickname 'The Mate'. He served as Conservative MP for North Lincolnshire between 1874 and 1880, and in 1893 he founded the Sports Club in London. In 1938 this merged with the East India Club, and there his portrait still hangs.

'The Mate' died at Park Place, St. James's on 10 October 1894, and was mourned by the whole racing community. An 'exceedingly beautiful' memorial service was held for him in the Guards' Chapel on 16 October, attended by 'a large array of distinguished officers' (see Wighton Advertiser, 20 October 1894). Many veterans of the rank and file who had fought under Astley in the Crimea also attended, for he had befriended them, treating them to annual dinners and showing genuine concern for their welfare. His oak coffin - draped with a Union Jack - lay at Elsham Hall for several days, where wreaths were sent by the Prince of Wales, Sir Claude de Crespigny, Lord Hastings and countless others. He was buried at the Church of All Saints, Elsham, Lincolnshire, to the hymn "Fight the Good Fight."

Sold with a fascinating archive, including:

(i)

A copy of Astley's memoirs, Fifty Years of My Life (London, Hurst and Blackett, 1894), in two volumes, this No. 537 of a special Limited Edition run, signed by Astley and presented to 'Major A. Sprott', cloth-bound, Astley's coat of arms in gold leaf on front cover, both with damage to spine.

(ii)

An extensive folder of research, including maps, illustrations,copied extracts from the London Gazette and Hart's Army List, and confirmation of medal entitlement.

Subject to 5% tax on Hammer Price in addition to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£2,600