Auction: 18003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 573

Sold by Order of a Direct Descendant

'The loss of such a distinguished officer as Captain Kirkpatrick in such a trivial affair is deplorable. He had gone through the Staff College at Sandhurst with brilliant success, and also gained the Distinguished Service Order by gallantry under fire. Nor was he inexperienced in African adventure and exploration. Major MacDonald must have reposed entire confidence in the ill-fated officer, or he would not have entrusted to him the command of a detachment marching into what was, practically, a "terra incognita". The massacre shows once more that the tribes in the African interior should never be trusted for a moment, no matter how friendly they may appear. It is not that they treasure any particular hatred, racial or religious, against Europeans, but accustomed as they are to plunder and murder one another whenever the temptation presents itself, they cannot refrain from attacks on white men when a safe opportunity occurs.'

An excessively rare - and important - Uganda 1897-98 operations D.S.O. pair awarded to Captain R. T. Kirkpatrick, Leinster Regiment, attached Uganda Rifles, who was murdered by tribesmen in one of the last incidents in the 'Scramble for Africa' at the end of the 19th Century

As part of Major J. R. L. MacDonald's expedition to reach Fashoda - to deny northern Uganda to a fast approaching French column from Senegal under Jean-Baptiste Marchand - Kirkpatrick came under fire from his own mutinous Soudanese troops on nine occasions

Subsequently, in believing the natives of Nakwai to be a 'fairly peaceable people', his judgement got the better of him, the former slaughtering him and his loyal team of followers in no uncertain manner: 'he had one spear thrust right through his chest in the neighbourhood of his heart and another spear thrust deep into his chest.'

Distinguished Service Order, V.R., silver-gilt and enamel, in case of issue; East and Central Africa 1897-99, 2 clasps, Lubwa's, Uganda 1897-98 (Captain R. T. Kirkpatrick. 1st. Leinster Regiment.), official correction to unit, nearly extremely fine (2)

D.S.O. London Gazette 20 May 1898:

'In recognition of services during the recent operation in Uganda.'

Richard Trench Kirkpatrick was born on 25 September 1865, the fifth son of Alexander Richard Kirkpatrick and Katherine Louisa (née Trench) Kirkpatrick, of Donacomper, County Kildare, Ireland. Described as 'a beautiful child, with bright clear open face, deep thoughtful looking eyes, and hair that made a sort of aureole round the head, gifted also with a goodness and sweetness of temper and disposition, such is rarely seen', he was sent aged ten to East Sheen, a school of 120 boys, where his Master wrote of him as, 'the best little boy he has ever had'. Transferring to Hutchinson's House, Rugby School, in September 1879, he continued to flourish for the next five years, winning an Exhibition to Oxford. To his deep regret, this promising opportunity had to be turned down, on account of cost and a reduction of rents having told heavily upon his father's means; he rather hurriedly decided upon entering the Army, with a view to serving in India and gaining pecuniary independence.

Having passed Sandhurst's preliminary examinations with 'unprecedented success', Kirkpatrick passed out in July 1885, and, barely a year after leaving Rugby, was gazetted to the 109th (2nd Leinster) Regiment, which he joined at Fermoy on 29.9.1885. According to his mother, 'he chafed at the inactivity of the life (in southern Ireland), and want of interest or real work for mind or body'; he was transferred to the other Battalion of his Regiment, the 100th, and set sail for Calcutta, India, in January 1888.

His first year was spent at Calcutta, where the damp heat tried his health but, in 1889, the Regiment moved to Agra, where Kirkpatrick 'enjoyed the life and entered with zest into all the games and sports of the Country'. During two-month's leave in the summer of 1892 in Kashmir, he bagged some fine specimens of heads and skins and, when the weather was poor, delighted in surrounding himself with books. It was about this time that an embryonic passion for exploration began to emerge, leading to him becoming a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society in 1897. It was, however, a time of sadness, the loss of a much-loved father leading to a period of deep grief, but also a deeper application to work; he passed the higher grade courses in both Hindistani and Persian and returned home to Donacomper in 1893, after five years and five months in India.

Gazetted Captain, Kirkpatrick entered Staff College in January 1894 and continued to flourish, spending his periods of leave in Ireland, with the exception of one which he spent abroad studying the battlefields of the Franco-Prussian War. In July, he went to London with his sister and two brothers, for the wedding of his brother Ivone to the Honourable Mary Hardinge; the following year he stood as Godfather to their first child, Queen Victoria being among one of the Godmothers. Passing out in December 1895, he rejoined his regiment at Tipperary, but, not caring for soldiering at home, was much pleased when, early in 1897, he was appointed to the Uganda Rifles. His departure was delayed until the summer due to an accident which laid him up for several weeks, but the Foreign Office kept open the position; 'he bade what was to be a final adieu to all he held most dear on earth, and left England in June 1897'.

The "Rolling Rewa"

Despite the reputation of his ship, the journey through the Mediterranean was, with one exception, a 'perfect delight' -no motion, no throbbing, gliding softly over a Summer sea:

'It is the lotus-eaters life, idle and lazy; you get up at 6 - spend the day sitting about the deck doing nothing in particular'. At Aden on 30 June, his mood changed following a period of rough weather:

'The ship is very small - 1100 tons - and not too clean so I took a dose of your bromide to-day and shall again before starting to-morrow.'

Arriving at Mombassa, Kirkpatrick found it impossible to form a caravan with which to proceed to Uganda as Major MacDonald had engaged every available porter for the immense caravan which he was forming for his 'Exploration Expedition'; as their roads lay together, MacDonald asked Kirkpatrick to join them - a gesture which the younger man gladly accepted. According to Kirkpatrick's mother, 'He was afterwards appointed as part of a Military escort to this MacDonald Expedition, and accompanied it to the end.'

First experiences of African travel - a nasty prang, a close encounter and some lightning

'I left Mombassa by rail a week ago with 120 porters for MacDonald's Expedition; they were on trucks piled up with rails and sleepers and I was in the brake van; it took us all day to do 55 miles. We had just left the station a few minutes after 6 o'c when the train got out of hand, running down a steep gradient; the line is intended for 20 miles an hour; I estimated the pace at 50. The engine ran off the rails; and the trucks were turned over, the men being buried under sleepers and rails; I escaped with a slight bump on the head. Three men were killed and about 12 severely injured; it was like a night-mare trying to get the injured out; I did not know any Swahiti and the men were too scared to do anything themselves and thought only of saving themselves. It was quite dark too.'

Reaching the Voi River, Kirkpatrick was informed of his new role to join the Soudanese on MacDonald's Expedition, survey the upper course of the Juba River, and delimit the spheres of interest. To begin with, all went well, but in mid-August 1897, MacDonald got laid up with fever and dysentery at Kibwezi and the caravan was halted. It was an opportunity to return to the hunt:

'Meanwhile, the other (Rhinocerous) was staring hard at me and looked like charging; if he would have gone off I'd have let him go, as one is enough to supply all the men with meat, but, as he seemed to mean fighting I thought I had better have first blow; he charged at once, and when he was about 10 yards off I dodged. Hitherto I'd been hunting, now I saw the other side of the game, for he turned after me as a terrier follows a rat.'

Back on track, the Expedition entered the Rift Valley in September 1897, and consistent with their bad luck and the harsh climate, further complications would strike the caravan :'a terrible thunderstorm came on whilst I was on top (of the hills bounding the centre of the Valley) and drenched me; one of the porters was struck by lightning and killed, and it was a rather unpleasant experience altogether.'

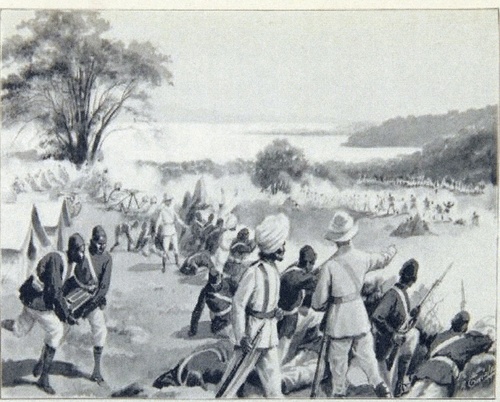

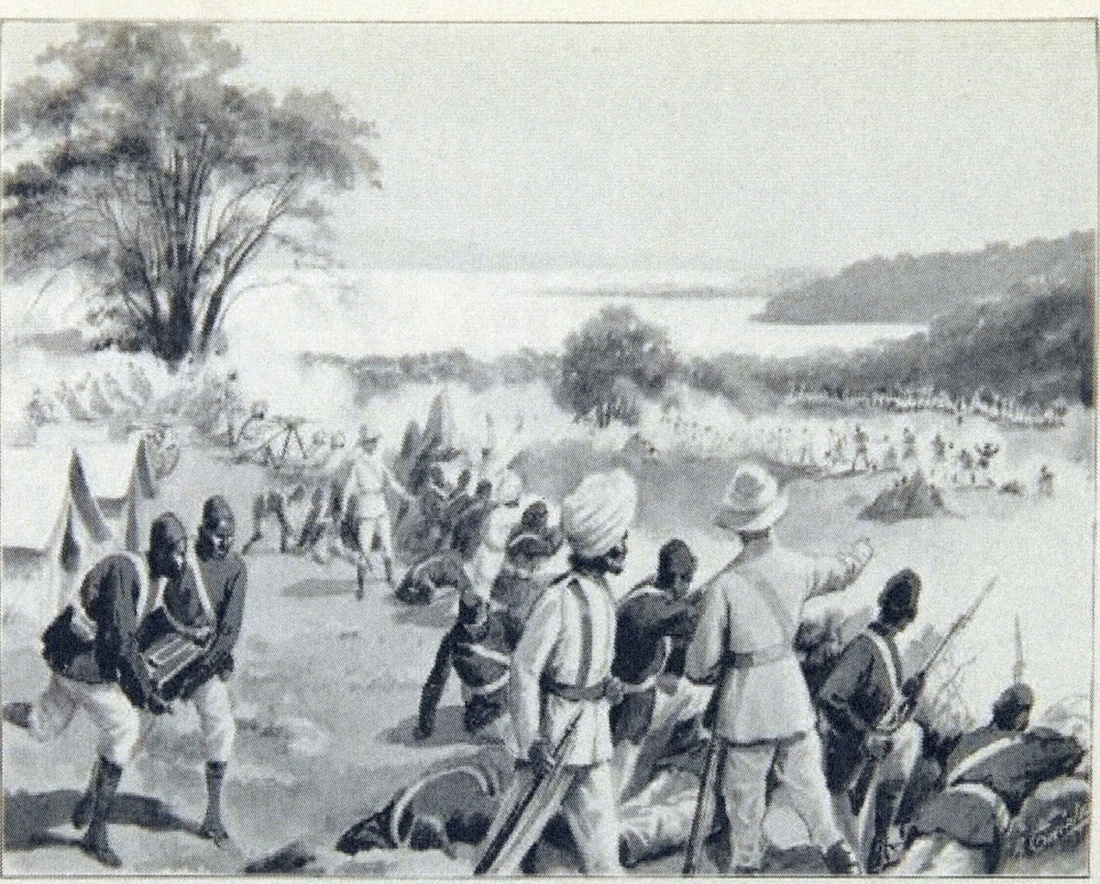

Mutiny: 'We have had a very anxious time - the Soudanese, 3 companies in all, bolted!'

At Mermia, on 9 October 1897, the Soudanese troops mutinied and made for the Ravine Station where they went into camp. Kirkpatrick followed and, together with another European Officer, Fielding, and half a company of 'loyal' troops, endeavoured to get the Soudanese to lay down their arms:

'After warning them several times, I ordered Fielding to open fire. His men fired certainly, but not in the direction of the Mutineers - after 3 volleys I saw that they could not be trusted to fight seriously and stopped the firing. The mutineers mostly ran away, but a few lay down and fired back about 20 or 30 shots; one had a fairly steady shot at me and put his bullet just over my head.'

Joined by MacDonald, there followed a series of bitter skirmishes where the Europeans and remaining troops were heavily outnumbered and vulnerable:

'We have 6 Europeans and 17 Sikhs with 2 Maxims, about 150 armed porters who don't know how to load or fire a rifle and are not fighting men, and about 30 Soudanese who are probably ready to desert. I think we are almost bound to attack them, as if allowed to go on to Uganda they could raise the garrisons there.' Kirkpatrick decided it was an appropriate time to write his will:

'As Sir Lucius O'Trigger says, "There's no being shot at without a little risk."'

The Soudanese are coming!

As a grey dawn broke on 19 October 1897, Kirkpatrick was awoken by his servant:

'I felt inclined to say "Let them come and do what they like, only let me sleep", but jumped up and ran out half dressed with my rifle and revolver.'

Suddenly a heavy fire erupted a few yards to the right. In panic, the porters ran to their tents and Kirkpatrick was forced to get them out and draw them up in fair order across the top of a hill covering the left flank:

'I then went down to an ant heap where the Soudanese were within 50 yards of our line and firing heavily; 14 men were killed and wounded close to this ant heap, of whom three were Europeans. The doctor and I lay down on it and kept them back by our fire; it was very warm work and the bullets kept throwing up dust in our faces.'

MacDonald sent up a Maxim, which jammed after a few minutes:

'He put it right, whilst I sat down beside it to keep down the Soudanese fire. Two Europeans and a Maxim of course drew it terribly. After he had gone I remained sitting by the Maxim. The Sikh working it filled me with admiration; the bullets were striking the gun and ground round in every direction; and sitting on the firing seat he was higher than anyone else. He never moved a muscle or an eye-lash even, but sat there quietly watching.'

After 5 hours in the firing line, the men were exhausted and down to 5 to 10 rounds each. Kirkpatrick, recognising the precarious situation, decided to launch one final attack; the Soudanese initially bolted, then held their ground, and then ran for their lives as Kirkpatrick and 20 men rushed on shouting and yelling. 100 Soudanese were killed, for the loss of 3 Europeans, 6 Sikhs and approximately 30 other troops.

In his despatch to Lord Salisbury, describing the battle, Major MacDonald noted: 'Captain Kirkpatrick kept his men well under control, and in the most gallant way led the counter-attack which practically decided the action.'

In another despatch, describing a severe engagement which took place on 24 November, Major MacDonald stated, 'Captain Kirkpatrick, the Leinster Regiment, is specially mentioned for his gallant conduct throughout the day and for conspicuous gallantry on the occasion of the enemy's attack on our right wing.'

For his undoubted bravery and skill, Kirkpatrick was awarded the Distinguished Service Order. The insignia was presented to him on Parade at Titi by MacDonald: 'The usual proceedings on such occasions were not strictly attended to as the men cheered him after the presentation.'

Masaka - closing the Mutiny down

After one and a half hours 'very severe fighting' at Masaka on 19 March 1898, the mutiny all but ended - the mutineers left 60 dead on the ground and the rest, many of them wounded, got away in the swamps of Lake Kioga, where many must have died either from their injuries or crocodiles.

Kirkpatrick returned to the task of MacDonald's Expedition and was sent north from Kampala to survey Lake Kiogia - or rather Choga by name - some 60 miles long and 40 miles wide. Kirkpatrick's findings were posthumously published in the Geographical Journal, Vol. XIII, No. 4, in April 1899:

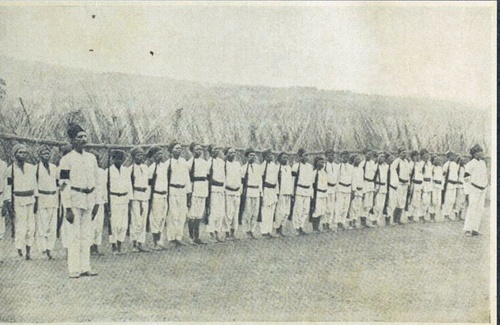

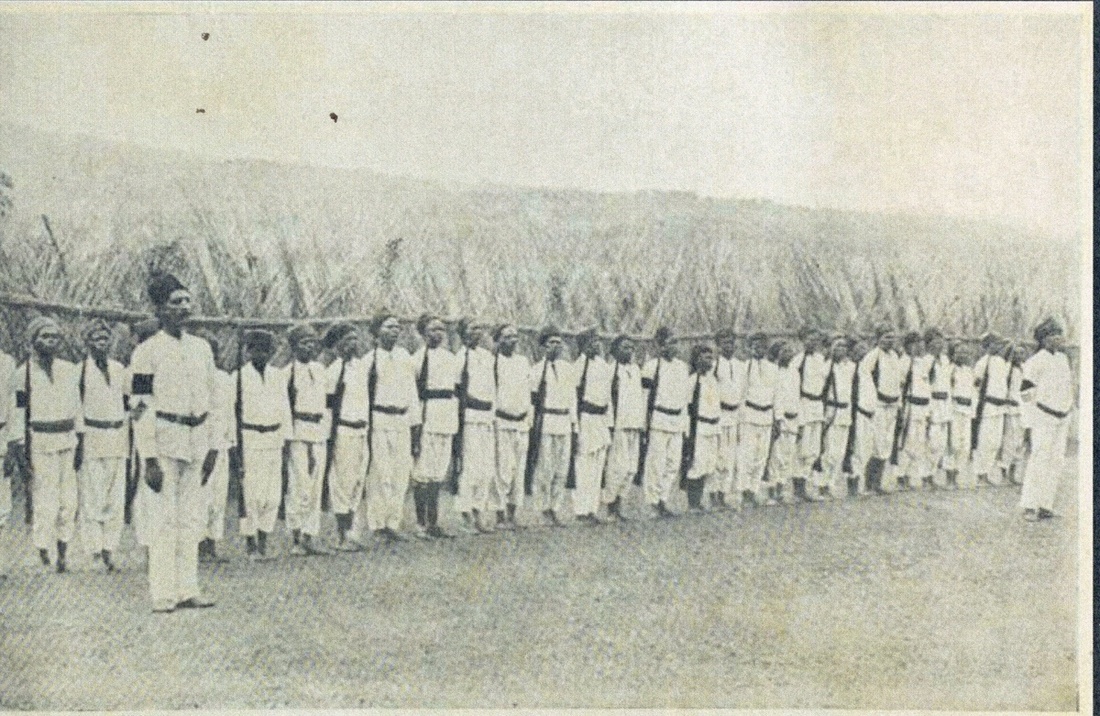

'The Wakedi live round the northern, eastern and south-eastern shores of the lake. We found those on the southern shore perfectly friendly, and exchanged presents with Kenaga, chief of Msara, the chief of Sabot, and Tende, chief of Kahera. The men are of good height, 5 feet 7 inches to 5 feet 10 inches, slightly built, and wiry. They wear as ornaments shells, beads, brass wire round the neck, and bracelets of brass wire and ivory. Most of them wear skins or a little bark cloth around the waist, but some are quite naked. They carry spears.'

A grisly end

In mid-November 1898, Kirkpatrick went out at Bukoda in an attempt to explore the Nakwai Hills, approximately 4.5 miles further west of the Makodo-kodoi River. His camp was visited by the Nakwai people on 25 November, who 'brought food for sale and appeared most friendly'. It was likely a ruse to determine the strength of camp and prepare a plan of robbery. The next day, confident of their friendship, Kirkpatrick arranged with the Nakwai people to take him up a high hill and plot it upon his map; with just a Karamogo guide, interpreter, gun bearers and four Askaris, Kirkpatrick left the rest of his men, some 60 odd, in camp.

In a letter to Kirkpatrick's father, MacDonald describes his son's fate:

'Kirkpatrick had sat down, they say under a tree in the shade to book some notes. When the natives gave the signal, he and five others were speared at once. The guide and one Askari escaped in the grass. Kirkpatrick's death must have been instantaneous, as he had one spear thrust right through his chest in the neighbourhood of his heart and another spear thrust deep into his chest.'

Kirkpatrick was buried in camp with military honours. In retaliation, the villages of the Nakwai were burned and over 100 natives killed. The leaders were arrested and seven were hanged.

Aged just 34, Kirkpatrick was heavily mourned by family, friends, and a host of 'old Rugs' from his happy days at school. A window was erected to his memory in Celbridge Church by his brothers and sisters, representing St. Michael, the Warrior Archangel, slaying the dragon, and a cross was put up in Donacomper Churchyard, close to where his father was buried. A brass was also placed in Birr Church, to his memory and that of two others, who had lost their lives in Africa, by his brother officers. His Will, written in haste during the Soudanese mutiny, left £715, 7s, 5d. to his mother.

Sold with an outstanding and thoroughly comprehensive account of his childhood, education, and experiences whilst serving with the Leinster Regiment in Africa: "Letters from Richard Trench Kirkpatrick - written whilst attached to Major MacDonald's Expedition in Central Africa from June 1897 to November 1898" - a typed account of all letters and correspondence relating to Kirkpatrick, prepared by his mother Katherine Louisa Kirkpatrick, at Donacomper, July 1900. Leather bound, 142 pp., approx. 35,000 words, including contemporary newspaper cuttings (17), and a report, 'Recent Events in the Uganda Protectorate', No. 17. February 1898.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£11,000