Auction: 18003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 442

'We now have a divisional photographer appointed to us. He is a regular cockney 'tout', not even a New Zealander and new been to New Zealand; and here he is appointed to the softest job in the whole division, given a commission in my regiment the N.Z.E. (honorary) if you please, given a motor car and driver all to himself, and what is worse for me, put into my mess and I have to sit next to him at every meal! I often think that there must be men in our division in the ranks who could ably fill that job without giving the pick of all soft jobs to an outsider like that.

The pictures of course will be appreciated in N.Z. and you will probably see many more now of our own troops than formerly in the papers. Pictures and photos are all very nice when you have no more serious work on hand, but I have had no time to show him round. I sent my batman with him one day. He has a cinema apparatus too, and poor old 'movie' as we call him was up close to the line soon after our last big fight to take photographs and got caught in a shelled area or in a barrage. He had his wits nearly scared away and instead of taking pictures he sat in a shell hole all day. I am inclined to laugh; but it is no joke for the fellow at the time! The point is he should not be there at all just for pictures!'

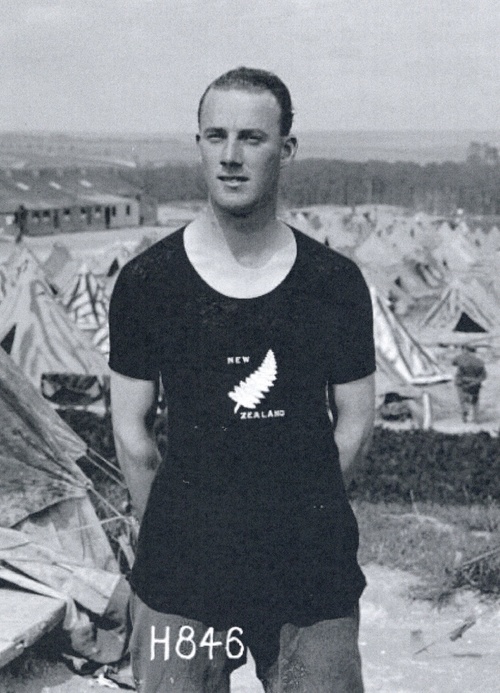

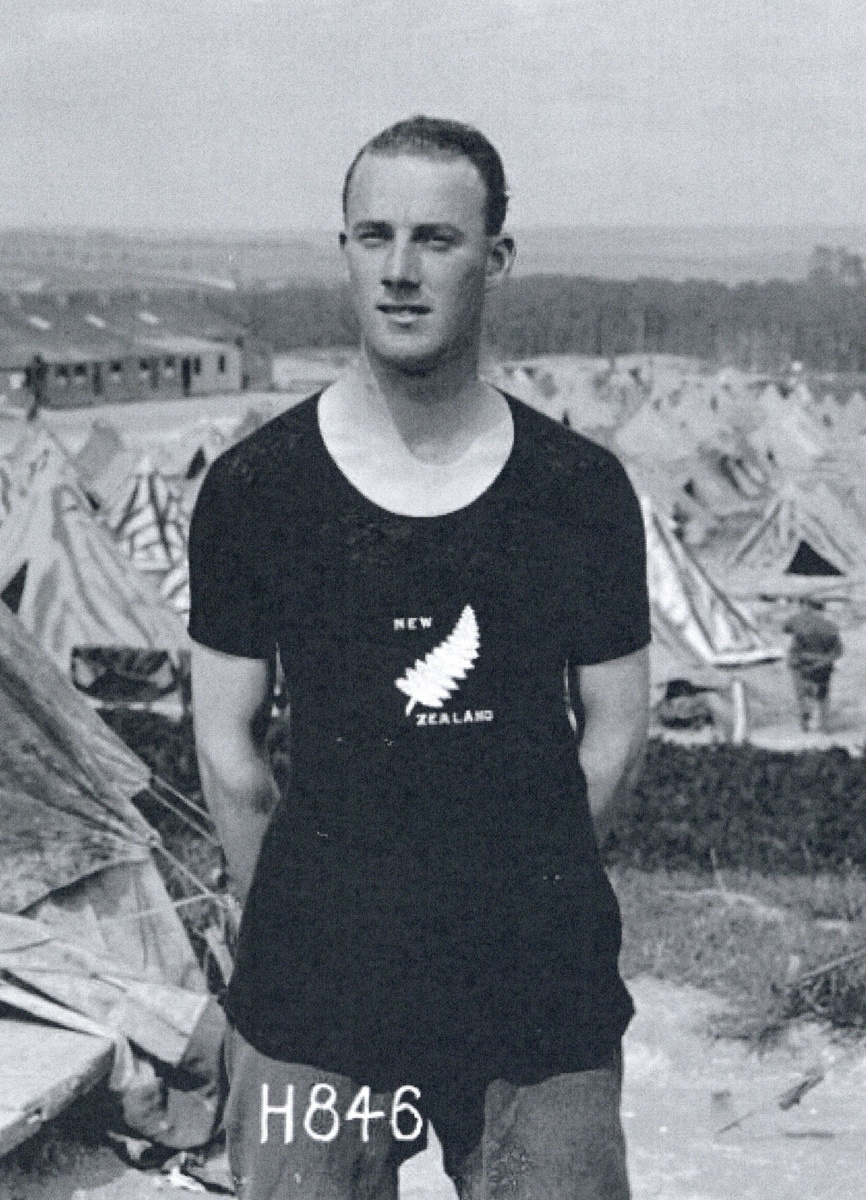

The important Great War pair awarded to Hon. Captain H. A. 'Movie' Sanders, N.Z.E.F., who served as New Zealand's Official Cameraman on the Western Front, 1917-1919: as a still photographer and cinematographer, he assembled the only significant 'pictorial' record of New Zealanders in that theatre of war

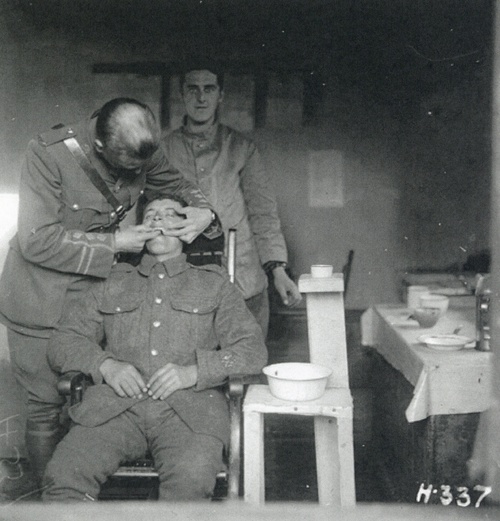

Although innocuous by today's standards, Sanders was not afraid to look beyond the faces of wounded men at casualty clearing stations and photograph controversial scenes, including rare images of New Zealand dead. Such imagery - in cases - was adjudged to be too disturbing, detailed and revealing by military censors of the time, but the depth of his work undoubtedly achieved a quite unique and highly important record of the lives of 'the Kiwis' in France

British War and Victory Medals (37194 Hon/Capt. H. A. Sanders. N.Z.E.F.), very fine (2)

Henry Armytage Bradley 'Movie' Sanders was born at Leytonstone, Essex, on 24 May 1886, the son of Harold Armytage Thomas Sanders and Louisa Augusta Sanders. His father was a Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society and had pursued a career in the manufacture of cameras and optical equipment, prior to moving into the production of motion pictures. In 1907, with Oliver G. Pike, he produced the first British wildlife film to be screened to a fee-paying audience; titled In Birdland, it saw both men dangling from ropes over coastal cliffs on England's East Coast, attempting to capture unprecedented footage of seabirds, including kittiwakes, gannets, cormorants and puffins. It proved hugely popular and, after further successes, such as The Egg Harvest at Flamborough Head (1908), and St. Kilda, Its People and Birds (1908), Harold became director of photography for Pathé Frères from 1910-20; unsurprisingly - perhaps - young Henry was smitten by his father's chosen profession.

'Fake News' is Nothing New

When the Great War broke out, moving pictures were taken and screened of almost every troop departure from New Zealand. Clips of troops leaving Albany were shown repeatedly to New Zealand audiences, and there was enormous demand for films from overseas which was largely unfulfilled; almost every street in every district in New Zealand had sent someone to fight and for the local picture house, nothing could cram-in the paying public than the prospect of seeing films and images of 'our boys'.

Censorship however, hugely affected what could be shown. Considered essential to the war effort, it was imposed long before New Zealand troops even fired their first shot. According to the New Zealand historian and archivist Jared Davidson:

'Censorship was designed to keep crucial information like troop movements from falling into enemy hands. But it was also used to conceal the war's grim realities from those at home and as a tool to keep domestic dissent in check.'

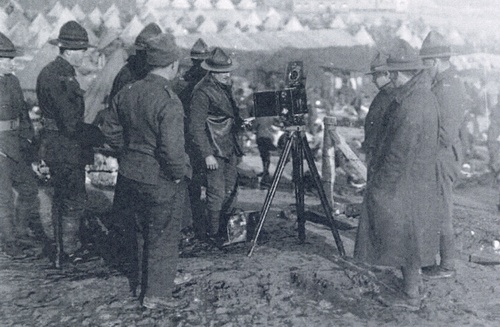

As a result, it was illegal to screen any film that had not been approved by a government censor and, in 1917, even the sale of invisible ink was banned. It was possible to obtain film of New Zealanders training in Egypt, and England, but pictures of them on the battlefront were confined to rare glimpses that concentrated more on the exploits of the major allies. It is possible to argue that film-making on the Great War battlefields was limited by restrictions imposed by the tripod-mounted camera and the nature of the terrain itself; usually there was little imagery that could be captured, a cameraman risking his life by standing-up to film a blurred landscape. In truth, even if such a cameraman did obtain good footage, it would be subject to the major impediment of censorship.

All this changed in October 1916, however, when the British - official film - The Battle of the Somme screened throughout New Zealand. It showed scenes of the British attack on the Somme in July 1916 and reached local audiences just as the New Zealand Division finished its part in the battle, suffering approximately 7,400 casualties in 23 days of fighting. Telegrams were arriving on New Zealand doorsteps at the same time as families were witnessing graphic scenes which included British dead and dying. The home press saw it as an:

' … awe-inspiring reproduction of the terrific events in which our brothers, our sons, and fathers are gloriously playing their parts to this day. If anything were needed to justify the existence of the cinematographer, it is to be found in the wonderful series of films of the opening of the British attack on the Somme on July 1.'

According to Malcolm Ross, the official New Zealand correspondent at the Front, armed with a pencil and prohibited from carrying a camera:

'Much was asked of them - they did more. As one watched them tired and sleepy in their worn and mud-caked clothing, coming out of the trenches into sodden bivouacs, one could not but wonder at their undaunted spirit … '

Now - for the first time - New Zealand's audiences had images to go with the fine words.

'Who is Sanders? Has he been appointed, if so, on what terms?'

In December 1916, under increasing public pressure for films of New Zealanders at the front, the Government cabled the N.Z. High Commissioner in London, Sir Thomas Mackenzie, asking if they could get the sole New Zealand rights to British official pictures taken at the front. The War Office response was positive, offering their own photographers to do the work - provided the New Zealand Government paid five pence per foot of film; however, as often the case, once the logistics were digested, the reality was that the War Office Cinematic Committee found that there were too many British Divisions to film and not enough cameramen. Mackenzie was informed that they could not honour their commitment and so he took the opportunity to negotiate with the War Office and appoint an official New Zealand cameraman.

On 23 March 1917, Mackenzie cabled the New Zealand Government stating that 'with the approval of the War Office, Henry Armytage Sanders has been appointed official photographer to the New Zealand Expeditionary Force with the rank of Lieutenant'.

In reply, James Allen, New Zealand Minister of Defence and Acting Prime Minister, did not mince his words:

' … who is Sanders?'

'Sanders is not known in this office, and enquiries at the New Zealand Picture Supplies were resultless, no one of the name being known to the picture business'.

In reality, Henry Sanders was at this stage an experienced cameraman who had been Pathé Frères' original British topographical cameraman for the Pathé Gazette; he had already filmed the war in Europe and was almost captured during the German advance into Belgium in 1914. Unknown in New Zealand, he likely gained the role through Mackenzie's personal past relationship with Pathé; approaching them seemed logical. Sanders was 30 years old and married with three children. He enlisted into the N.Z.E.F. in England on 8 March 1917 and arrived on the Western Front during the preparations for the Messines offensive.

Frosty reception

The New Zealand Division had the reputation of being one of the finest fighting Divisions in France. Their first impressions of Sanders were not positive; they saw his life as cushy and his rank as unwarranted. Yet this opinion changed over time as Sanders did place himself in the action, in harm's way, in order to carry out his work. Lawrence 'Curly' Blyth, who later became the last 'Kiwi' Great War Veteran to pass away, aged 105, in 2001, described Sander's filming whist under fire in the frontline trenches:

'My company had taken the railway line and I was doing a little reconnaissance. While I was there, I came under a certain amount of fire from the Germans in the town and I got down in a small trench to take cover.

In two seconds time, I found on my left-hand side was a photographer, busy turning on the handle, taking snaps of the whole proceedings. I remember asking him how come he should be right up in the front line like this and he said it was part of his job, and he proceeded on his way to keep turning the handle, while we both took a certain amount of cover.'

Sander's official photographs - identified by the letter 'H' in archives - are almost the only New Zealand photographic record of life on the Western Front. As per Part 3 of 'War Office impositions' for developing photographs and films, the name of the Official Photographer could not appear, hence Sanders utilised the 'H', an easily recognisable feature.

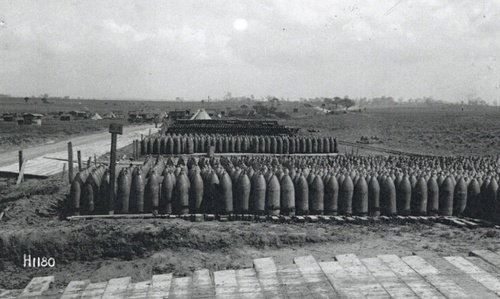

On 30 January 1918, a film of New Zealand Prime Minister W. F. Massey visiting the front was shown to New Zealand audiences; in April, two further films by Sanders were shown: these were the New Zealand Battalion on the March and Inspection of New Zealand Troops by Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig. The latter successfully captured the size of the Division, but it would be the films which were unseen by the 'Kiwi' public which perhaps represented his 'best' work; the honesty and accurate representation displayed in the Work of the New Zealand Medical Corps, which was shot in June 1917, was too revealing for the censors, but is seen today as a comprehensive and invaluable look at the N.Z. casualty evacuation system.

Approximately 12 films by Sanders survive to tell the story of the New Zealand medical services and artillery on the Western Front, together with a large series of 'visit' films. Almost all the films of Staff Sergeant Thomas Scale, who was the New Zealand official photographer and cameraman in the United Kingdom, have perished. Thankfully, more than a thousand of Sanders' photographs have survived and it is hoped that footage of the final New Zealand attack at Le Quesnoy in November 1918 will one day turn up. According to Christopher Pugsley, author of The Camera in the Crowd: Filming New Zealand in Peace and War, 1895-1920:

'Look, anything is possible and one dreams of that.'

Attached to a Tunnelling Company in 1917, and promoted to the honorary rank of Captain, Sanders survived the war, largely physically unscathed bar a bout of scabies. He was discharged in April 1919 and returned to civilian life as a news film editor.

Twice married, firstly to Maude Marie Tugwell at St. Margaret's, Westminster in 1904, and secondly, to Lilian Mary Spurge at West Ham in 1910, Sanders spent the 1920s and 1930s working in Britain and America. He died at Ploughney, Oxfordshire, on 5 May 1936, aged 49 years; sold with extensive copied research.

Reference Sources:

https://ojs.victoria.ac.nz/jnzs/article/download/483/392/

http://www.aucklandmuseum.com/war-memorial/online-cenotaph/record/C143444

https://www.newshub.co.nz/home/new-zealand/2018/01/new-zealand-s-final-attack-of-wwi-was-filmed-a-century-ago.html

https://www.revolvy.com/topic/Harold%20Armytage%20Sanders

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£1,400