Auction: 18003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 318

Family group:

'Sir Robert Anderson is one of the men to whom the country, without knowing it, owes a great debt.'

Raymond Blathwayt (1855-1935) on the achievements of Sir Robert Anderson, K.C.B., LL.D.

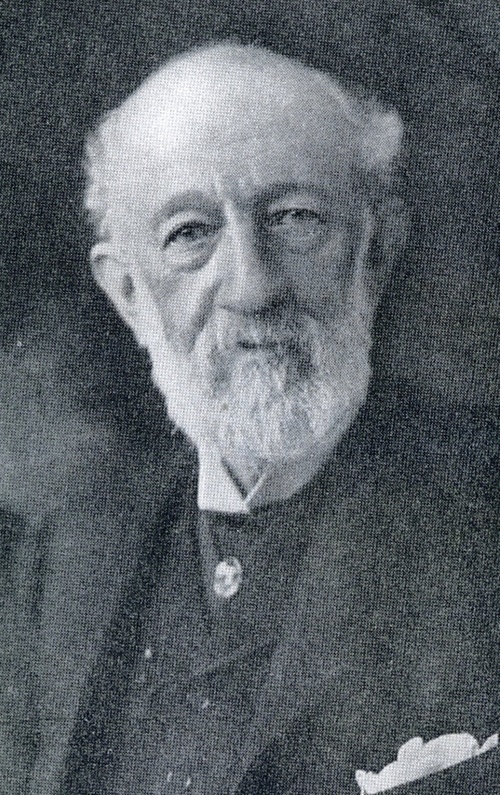

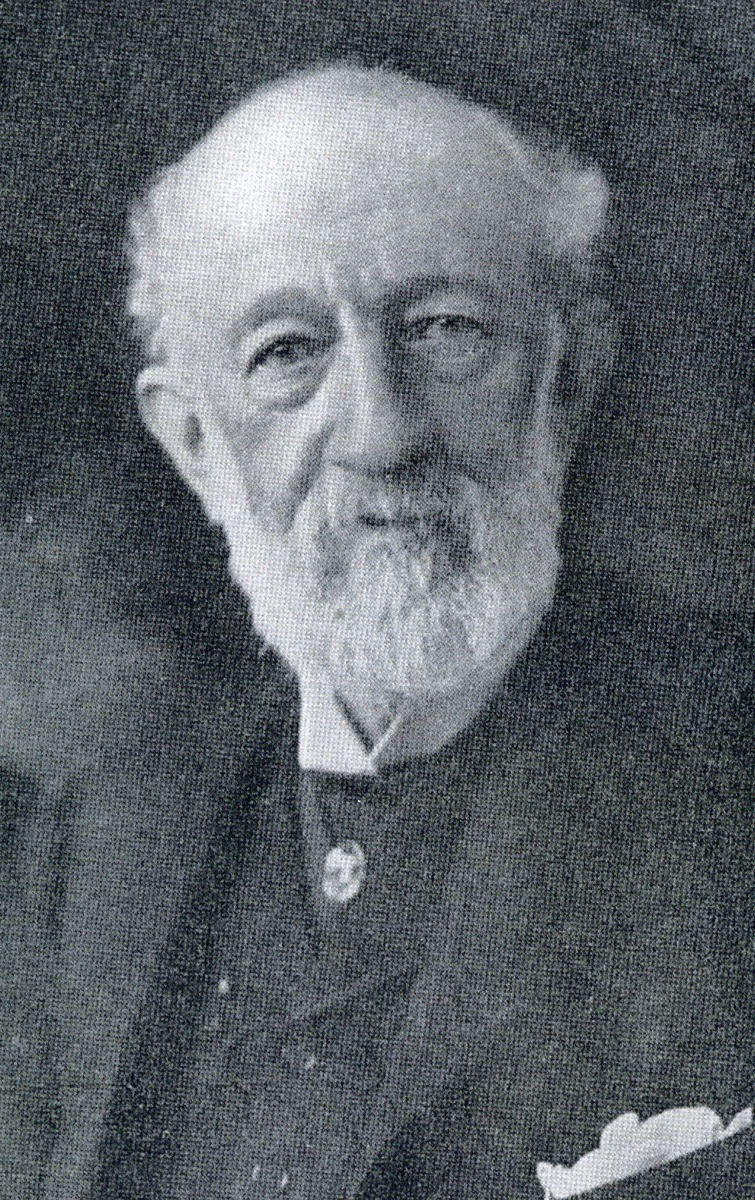

The fascinating and historically significant pair awarded to Sir Robert Anderson, K.C.B., LL.D., Metropolitan Police; as Assistant Commissioner of Scotland Yard's Criminal Investigation Department, Anderson led the investigation into Jack the Ripper's murders and was the most senior police officer on the case

Anderson's conduct during the 1888 'Whitechapel Murders' scare was highly controversial, his absence during much of the investigation provoking a public outcry; he nevertheless led a thorough post-mortem of Mary Kelly's murder, wading through her blood at the murder scene and later claiming to know the Ripper's identity

Earlier in his career, Anderson managed the spy Thomas Beach during the height of the Fenian Raids; he foiled a planned Fenian insurrection in Ireland and led a fledgling counter-terrorism unit

Anderson was also a prominent theologian and philosopher; among his most devoted readers were William Ewart Gladstone, Kaiser Wilhelm II and Queen Victoria

Jubilee 1897, silver, unnamed as issued; Jubilee 1897, Metropolitan Police, bronze (Robert Anderson. Esq. C.B.), mounted as worn, with somewhat discoloured original ribbons, the first with minor scratches to obverse, thus very fine or better (2)

Three: Captain A. P. Moore-Anderson, South African Force

1914-15 Star (Capt. A. P. Moore-Anderson S.A.S.S.F.AMB.S.A.M.C.); British War and Victory Medals 1914-19, with M.I.D. oak leaves (Capt. A. P. Moore-Anderson.), good very fine (3)

Robert Anderson was born at Mountjoy Square, Dublin in May 1841, the son of Matthew Anderson, Crown Solicitor at Dublin Castle. Of Ulster Scots descent, his Protestant ancestors defended Londonderry during the siege of 1689. Educated privately, he began a business apprenticeship in a brewery but left after eighteen months to study law at Boulogne and Paris. Robert was born into a legal family: his older brother Samuel became a barrister and his sister Annie married Sir Walter Boyd, 1st Baronet (1833-1918), a towering figure of the Irish judiciary and a staunch upholder of British rule.

Anderson entered Trinity College, Dublin in 1859. Three years later he graduated as a Bachelor of Arts with Moderatorship and medal; in 1863 he was called to the Irish Bar.

Irish Agent

In 1865 Anderson became a legal assistant to the Crown Solicitor at Dublin Castle. There he worked under his older brother Samuel, who showed him papers relating to the trials of Fenians. Named after the legendary Irish warrior Fionn mac Cumhaill and his loyal band, the 'Fianna', the Fenian Brotherhood was an Irish republican organisation founded in America by John O'Mahony in 1858. Fenians believed in Ireland's natural right to independence, and viewed armed rebellion as the only means of achieving that right. The British establishment used 'Fenianism' as an umbrella term for any form of Irish nationalist sentiment.

In August 1866, Anderson was put in charge of intelligence reports coming in from America on Fenian activities. Four months earlier, O'Mahony had launched the first of five 'Fenian Raids' into Canada, attempting to seize Campobello Island in New Brunswick from the British. Anderson was tasked with planting spies and informants in Fenian circles. In his memoirs, he recalled:

'My first Fenian informant was shot like a dog on returning to New York. In communicating the man's information to Lord Mayo, then Chief Secretary, I gave him the poor fellow's name and some particulars respecting him, and these he passed on to the Lord-Lieutenant as they sat together one evening over the dinner-table at the Viceregal Lodge. A servant happened to be behind the screen which covered the service-door of the dining-room, and he overheard the conversation and repeated it in the servants' hall.'

The mood in Dublin was very tense. James Stephens, a participant in the failed 1848 Irish Rebellion, had returned to the city after an exile in Paris, establishing a network of Fenians known as the Irish Republican Brotherhood. Anderson intercepted letters from O'Mahony to Stephens promising funds and American weaponry for a rising in Ireland. When a group of Irish-American officers landed at Cork in February 1867, they expected to take command of a Fenian army. Instead, thanks to Anderson's superb use of informers, they were arrested on arrival by the Royal Irish Constabulary. The Fenians were thus deprived of matériel and practically leaderless. Although riots took place in Dublin and Limerick on 5 March, the planned co-ordinated rising never transpired. Sir Thomas Larcom, Lord Mayo's Under Secretary, wrote to Anderson expressing his gratitude:

'I owe a great deal more to you than you do to me - and so does the public; for I do not know what we should have done without your brother and you. And it has been no common time or ordinary duty with which we have been engaged.'

On 13 September, a bomb planted by a Fenian terrorist exploded outside Clerkenwell Gaol, where a prominent Fenian was being held. Known as the 'Clerkenwell Outrage', this unsuccessful jailbreak attempt resulted in 12 civilian deaths, 120 civilian injuries, and severe damage to nearby houses. Anderson arrived in London the following day. Appointed Irish Agent at the Home Office, he became legal adviser and secretary of a fledgling secret department aimed at combatting the terrorist threat. In 1869 he was given sole responsibility for managing the spy Major Henri Le Caron, whose real name was Thomas Beach. Beach spent 21 years infiltrating Fenian circles, thwarting their plots. The intelligence he sent back to Anderson in 1870 enabled the British to intercept John O'Neill's Fenian force near Saint-Armand, Quebec. Canadian militia units soundly defeated the Fenians at the Battle of Eccles Hill on 25 May. In his autobiography, Beach showered praise on Anderson:

'He never wavered or grew lax in his care. He proved to me, not the ordinary official supervisor, but a kind trusty friend and adviser, ever watchful in my interests, ever sympathising with my dangers and difficulties. To him, and to him alone, was I known as a Secret Service agent during the whole of the twenty-one years of which I speak. Therein lay the secret of my safety. If others less worthy of the trust than he had been charged with the knowledge of my identity, then I fear I should not be here to-day on English soil quietly penning these lines.'

Anderson would advise the Home Office on political crime for the rest of his career. In 1875 he received an honorary LL.D. from his Alma Mater, Trinity College, Dublin. By May 1884 Fenianism was in decline, and Anderson was formally relieved of all duties 'relative to Fenianism in London'. After three years as Secretary to the new Prison Commission, in February 1887 he was asked to join the Metropolitan Police's Criminal Investigation Department (C.I.D.) at Scotland Yard, headed by Assistant Commissioner James Monro. He worked with Monro to form the Special Irish Branch, which became Special Branch (disbanded in 2005).

Under Monro's leadership the C.I.D. became increasingly autonomous and influential; a rift developed with Sir Charles Warren, Monro's nominal superior as Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police. Neither man could abide the other's company. On 29 August 1888, Monro could stand it no longer and resigned. Anderson succeeded Monro as Assistant Commissioner on 1 September 1888.

The Whitechapel Murders

'I sometimes think myself an unfortunate man, for between twelve and one on the morning of the day I took up my position here [as Assistant Commissioner] the first Whitechapel murder occurred.'

Anderson is interviewed in Cassell's Saturday Journal (11 June 1892, pp. 895-897).

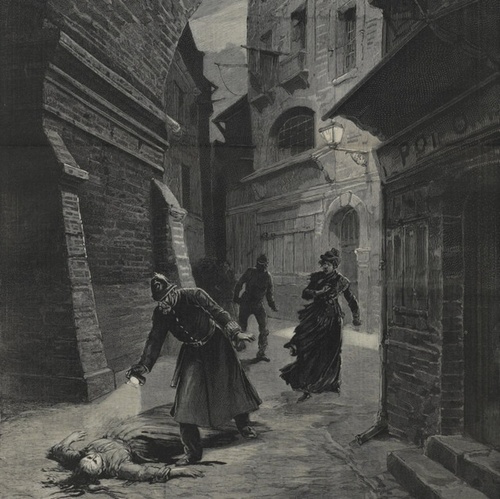

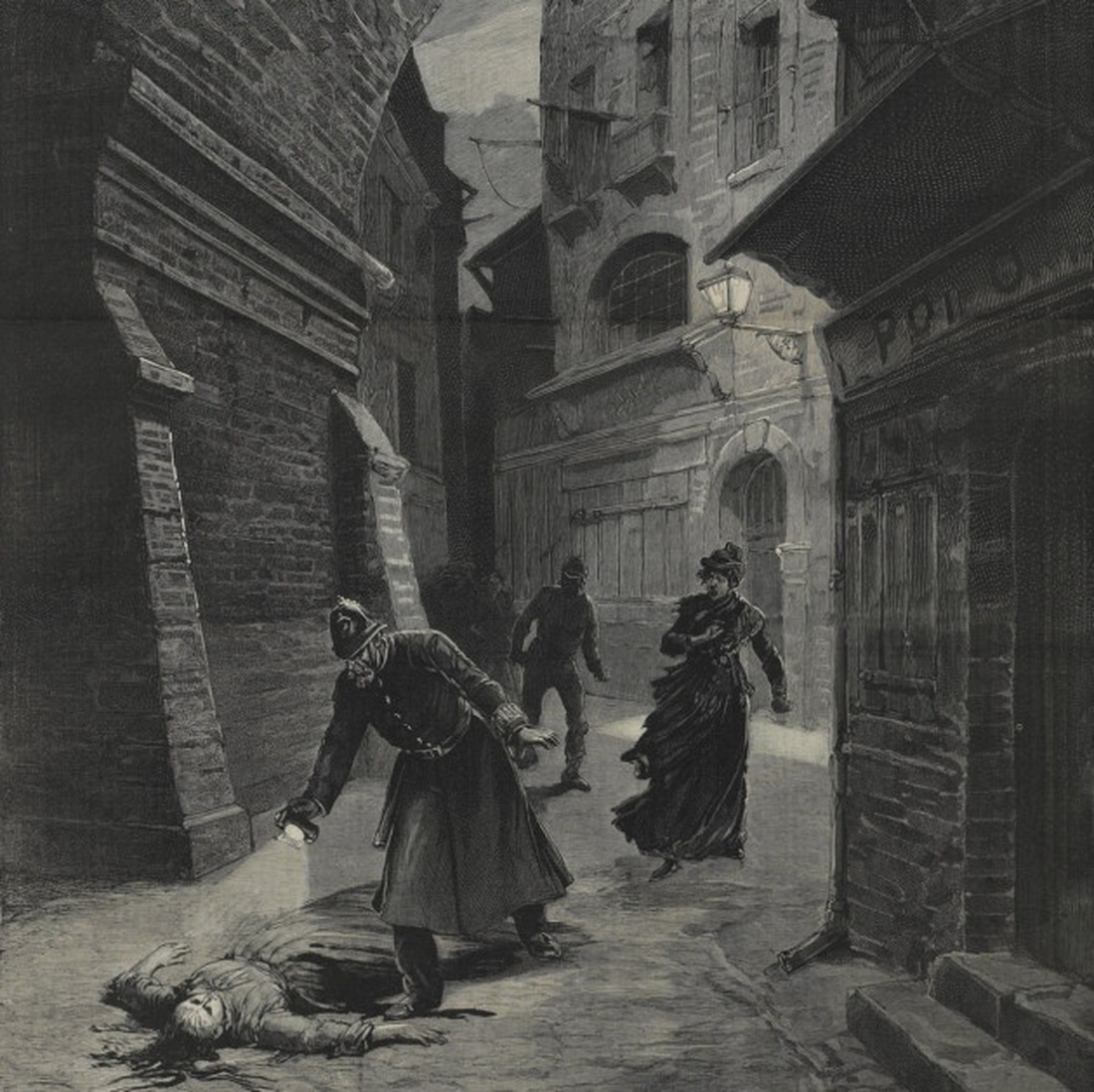

At 3.45 a.m. that same day, Mary Ann Nichols' mutilated body was found by Charles Cross, a cart driver, in front of a stable entrance in Buck's Row, Whitechapel. Her throat had been slit twice from left to right, creating a hideous gash two inches wide; her intestines were sprawled across the road. Lloyd's Weekly Newspaper called it: 'A murder excelling in atrocity any that has disgraced even the East-end.' Nichols' murder was a mere prelude of things to come.

Another prostitute, Martha Tabram, had been murdered in Whitechapel at 2.30 a.m. on 7 August. Her body was discovered at George Yard with 39 stab wounds. Although modern experts no longer link Tabram's murder with the 'Whitechapel Murders' (since Tabram was stabbed rather than slashed), London newspapers quickly formed a connection, fanning the flames of public hysteria. One lady, on reading the description of Nichol's murder in the Pall Mall Gazette, reportedly passed out and died.

Meanwhile at the C.I.D., Anderson was finding it difficult to acclimatise. Monro had been extremely popular: Anderson recalled in his autobiography that Monro was not 'an easy man to follow', and that C.I.D. officers were 'demoralised by the treatment accorded to their late chief' by Sir Charles Warren. Factions created by the Monro-Warren power struggle still lingered, and since Anderson had worked with Monro on political crime matters, he was assumed by Warren's supporters to be in league with Monro. The Metropolitan Police were about to be tested as never before. It was not an auspicious start.

Anderson had been working continuously for years, and the strain was beginning to tell. Dr. Gilbart Smith, of Harley Street, insisted that he must have two months' complete rest, adding that he would probably give Anderson a certificate for a further two months' 'sick leave'. Deciding that one month would be sufficient to restore his health, Anderson informed the Home Secretary of his decision to take a month's holiday in Switzerland. He crossed the Channel on Saturday 8 September.

At 6 a.m. that very day, Annie Chapman's mutilated body was found near a doorway in the back yard of 29 Hanbury Street, Spitalfields. As with Mary Ann Nichols, Chapman's thoat had been cut from left to right and she had been disembowelled. More horrific was the fact that her uterus had been sliced out in a single movement with a blade about 6-8 inches long. The pathologist George Phillips opined that her murderer must have possessed considerable anatomical knowledge. Samuel Montagu, MP for Whitechapel, offered a reward of £100 for the killer. Rumours that the murders were Jewish ritual killings led to mass anti-Semitic demonstrations. Controlling angry crowds distracted the police from the main task of investigating the murder. As a result, when the inquest started on Monday 10 September, the police lacked evidence and had been unable to locate witnesses. The Daily Chronicle did not hold back:

'The Metropolitan Police are simply letting the first city of the world lapse into primeval savagery. Whitechapel, according to their own admission, has for a year or two been swarming with gangs of blackguards, who live by extorting, under threats of brutal torture, from the unfortunate women who flit through its alleys like midnight birds of prey. There is now reason to think that they have finally handed over this afflicted neighbourhood to the tender mercies of an assassin, who butchers his victims almost within earshot of the street patrols. The people of London will no longer tolerate the crotchets of Scotland Yard.'

That night's Evening Standard further decried the police investigation:

'The affair is one which should put the police authorities on their mettle, for if they bungle it their credit will be disastrously impaired and a serious blow given to public confidence in their abilities. This, of course, is well understood at headquarters.'

Anderson's absence had left 'headquarters' hopelessly confused, with Chief Inspector Donald Swanson doing his best to co-ordinate the investigation. Sunday 30 September played host to the "double event", the murder of Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes within an hour of each other. Stride's body was discovered at 1 a.m. in Dutfield's Yard, Whitechapel, her throat cut from left to right, while Eddowes' mutilated body was found at 1.45 a.m. by PC Edward Watkins at the south-west corner of Mitre Square. Since Eddowes' murder took place within the Square Mile, the City of London Police took charge of that inquiry and so the investigation became disjointed. On 1 October, the Central News Agency received a postcard from a man claiming to be the murderer. The postcard was signed, "Jack the Ripper".

When an unidentified female torso was found the next day in the basement of New Scotland Yard, still under construction, the Metropolitan Police were ridiculed. The Daily Telegraph called for the resignation of Henry Matthews, the Home Secretary. Pressure now mounted on Anderson to return, as this furious tirade in the Pall Mall Gazette (8 October 1888) reveals:

'Although Dr. Anderson is nominally at the head of the C.I.D. he is only there in spirit. At a time when the world is ringing with outcries against the officials who allow murder to stalk unchecked through the most densely crowded quarter of the metropolis, the chief official who is responsible for the detection of the murderer is as invisible to Londoners as the murderer himself. You may seek Dr. Anderson in Scotland-yard, you may look for him in Whitehall-place, but you will not find him, for he is not there. Dr. Anderson, with all the arduous duties of his office still to learn, is preparing himself for his apprenticeship by taking a pleasant holiday in Switzerland! No one grudges him his holiday. But just at present it does strike the uninstructed observer as a little odd that the chief of London's intelligence department in the battle, the losing battle which the police are waging against crime, should find it possible to be idling in the Alps.'

In his autobiography, The Lighter Side of my Official Life (1910), Anderson recalls:

'Letters from Whitehall decided me to spend the last week of my holiday in Paris, that I might be in touch with my office. On the night of my arrival in the French capital two more victims [Stride and Eddowes] fell to the knife of the murder-fiend; and the next day's post brought me an urgent appeal from Mr. Matthews to return to London; and of course I complied.

On my return I found the Jack-the-Ripper scare in full swing. When the stolid English go in for a scare they take leave of all moderation and common sense. If nonsense were solid, the nonsense that was talked and written about those murders would sink a Dreadnought… it is enough to say that the wretched victims belonged to a very small class of degraded women who frequent the East End streets after midnight, in the hope of inveigling belated drunkards, or men as degraded as themselves.'

Anderson's unsympathetic attitude towards the Ripper's victims jars with modern attitudes, as it jarred with general feeling at the time. Influenced by thinkers such as George Bernard Shaw, newspapers increasingly linked the murders to the poverty which afflicted the East End. Punch's cartoonist John Tenniel published a cartoon entitled "The Nemesis of Neglect". Jack the Ripper, knife in hand, is portrayed as the ghoulish image of social destitution, with 'Crime' written above his head.

Unsurprisingly, Anderson sheds little light on the heated correspondence which must have taken place between himself and Scotland Yard officials during his absence. He does, however, mention a revealing conversation between himself and Henry Matthews, the Home Secretary, whose political career hung in the balance. He writes:

'I spent the day of my return to town, and half the following night, in reinvestigating the whole case, and next day I had a long conference on the subject with the Secretary of State and the Chief Commissioner of Police. "We hold you responsible to find the murderer," was Mr. Matthews' greeting to me. My answer was to decline the responsibility. "I hold myself responsible," I said, "to take all legitimate means to find him."'

Anderson's words were borne out by his actions. He resumed his role at the C.I.D. on 6 October, and by 19 October, the police had interviewed more than 2,000 people, investigated 'upwards of 100', and detained 80 (Inspector Donald Swanson's report to the Home Office, HO 144/221/A49301C, refers). The investigation gathered pace, becoming more targeted and cohesive. Anderson took the controversial step of refusing police protection to prostitutes in Whitechapel: as intended, this actually encouraged the prostitutes to take fewer risks and to approach the police if threatened. This single action may have saved countless lives. Positioning plain-clothes police officers throughout the East End, Anderson tried to anticipate the Ripper's murders.

He was unable to prevent the murder of Mary Jane Kelly on 9 November. The stomach-turning tangle of her mutilated body surely ranks among the 19th century's most appalling images (see https://whitechapeljack.com/the-whitechapel-murders/mary-jane-kelly/, note: strong constitution required). Kelly's body was discovered at her home in 13 Miller's Court, a drab single room just twelve square feet in size. When the police broke in at 1.30 p.m. on 10 November, the sight that greeted them was reported in Illustrated Police News:

'The throat had been cut right across with a knife, nearly severing the head from the body. The abdomen had been partially ripped open, and both of the breasts had been cut from the body, the left arm, like the head, hung to the body by the skin only. The nose had been cut off, the forehead skinned, and the thighs down to the feet, stripped of the flesh. The abdomen had been slashed with a knife right across downwards, and the liver and entrails wrenched away. The entrails and other portions of the frame were missing, but the liver etc., it is said were placed beneath the feet of this poor victim. The flesh from the thighs and legs, together with the breasts and nose, had been placed by the murderer on the table.'

When Anderson entered Kelly's room he slipped on the floor, which was slick with blood and water. One theory holds that the murderer could not avoid being spattered with gore and was obliged to wash himself down after the deed, hence the water (see Fairclough 1992, 167). The Times reported that Kelly's clothes were neatly folded on a side table, and she wore only a slight chemise; she had evidently undressed for her murderer, believing him to be a paying client. Kelly's death occurred in a private room rather than on a street, giving Jack the Ripper time to commit the full repertoire of his atrocities without being discovered. This explains why Kelly's murder was the most savage and methodical. It also suggests that the police net was closing, as the Ripper was compelled to stay in private rooms. Anderson was breathing down his neck.

Mary Jane Kelly was the last of Jack the Ripper's confirmed victims. On 19 November she was buried in an unmarked pauper's grave at St. Patrick's Roman Catholic Cemetery, Leytonstone. Mourners flocked to the scene, desperate to touch Kelly's coffin and unaware that the Ripper's reign of terror had ended.

Jack the Ripper, of course, was never identified. That is to say, he was never identified publicly. Throughout the investigation, Anderson and the police had withheld key information from the Press, denying journalists access to the crime scenes. On 1 October, following the double murder of Stride and Eddowes, the Yorkshire Post reported that 'the police apparently have strict orders to close all channels of information to members of the press.' On the same day the New York Times claimed that the police 'devote their entire energies to preventing the press from getting at the facts. They deny to reporters a sight of the scene or bodies, and give them no information whatever.'

Was there a police cover-up? The police's silence served no useful purpose in the hunt for the murderer, and it led to newspapers publishing fanciful cartoons of the Ripper's appearance which may have set the investigation back. The mystery is made even more tantalising by Anderson's comment in Chapter IX of his autobiography:

'Having regard to the interest attaching to this case, I am almost tempted to disclose the identity of the murderer. But no public benefit would result from such a course, and the traditions of my old department would suffer. I will merely add that the only person who had ever had a good view of the murderer unhesitatingly identified the suspect the instant he was confronted with him; but he refused to give evidence against him.'

K.C.B.

The Whitechapel Murders were a glitch in Anderson's otherwise successful career. Crime rates fell dramatically in the 12 years during which he remained Assistant Commissioner of the C.I.D. During the period 1879-1883, an annual average of 4,856 crimes against property were committed in London. By 1899, Anderson's penultimate year in office, this figure had dropped to 2,439. This was despite the population of London having increased by 2 million (Anderson 1910, 141). In Scotland Yard and the Metropolitan Police (1929), Sir John Moylan gives effusive praise:

'The period 1890 to 1900 proved to be one during which there was an almost continuous decrease in crime. . . By signal successes in sensational murder cases such as that of Neil Cream, the poisoner, and Milsom and Fowler, the Muswell Hill murderers, and by steady achievement in the less advertized, everyday business of dealing with rogues in general, the C.I.D. built up in the "nineties" a world-wide reputation for efficiency in crime detection.'

Anderson was made a Companion of the Bath in the 1896 New Year's Honours List, and on his retirement in 1901 was elevated to K.C.B. Parliament granted him a pension of £900 per annum (Hansard, 12 April 1910). On the floor of the House of Commons, W. H. Smith stated that Sir Robert 'had discharged his duties with perfect faithfulness to the public.' The esteemed writer Raymond Blathwayt, in Great Thoughts (1902), wrote:

'Sir Robert Anderson is one of the men to whom the country, without knowing it, owes a great debt. Silently and efficiently he and his family have worked for years in high Government positions, and they have worked with a sweet reasonableness and an absence of hide-bound, red-taped officialism, which is as delightful as it is exceptional.'

Anderson wrote prolifically on religious matters, authoring 21 known works. Like his ancestors, the Prentice Boys of Londonderry, he was a staunch defender of the Protestant Reformation. In The Buddha of Christendom (1899), he pitted the Bible against organised Christianity (specifically the Roman Catholic Church) and took the side of Scripture. In A Doubter's Doubts about Science and Religion (1889), he analysed Darwin's evolutionary theories and argued that the creation principle was compatible with natural selection. In the Preface to this treatise, William Ewart Gladstone extolled its 'care, force, and exactitude'. He developed an avid following. Numbered among his most enthusiastic readers were Queen Victoria, Queen Alexandra, Queen Mary and Kaiser Wilhelm II.

On 4 March 1873 he married Lady Agnes Moore, sister of Ponsonby Moore, 9th Earl of Drogheda. They had four sons and one daughter, and lived at 39 Linden Gardens, Notting Hill.

Anderson always held 'uncompromisingly Unionist views' (Moore-Anderson 1919, 29), and must have been horrified by the Easter Rising in April 1916. Robert Anderson died on 15 November 1918. A year later, his son Arthur published Sir Robert Anderson K.C.B., LL.D.: A Tribute and Memoir (1919). This remarkable volume reveals the extent of his intellect and abilities, and the intense admiration in which he was held by the public; sold with a copy of Anderson's autobiography, The Lighter Side of my Official Life (1910), and a copy of his son Arthur's aforementioned book.

Recommended reading:

Anderson, Sir R., The Lighter Side of my Official Life (London, 1910).

Begg, P., Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History (London, 2003).

Evans, S. P., and Rumbelow, D., Jack the Ripper: Scotland Yard Investigates (Stroud, 2006).

Moore-Anderson, A. P., Sir Robert Anderson K.C.B., LL.D.: A Tribute and Memoir (London, 1919).

Moylan, Sir J., Scotland Yard and the Metropolitan Police (London, 1929).

Senior, H., The last invasion of Canada: The Fenian raids, 1866-1870 (Toronto, 2011).

Wiersbe, W., 'Introduction' to Anderson, Sir R., Redemption Truths (Grand Rapids, 1980).

'Representative Men at Home: Dr. Anderson at New Scotland Yard', Cassell's Saturday Journal (11 June 1892, 895-897).

https://www.jack-the-ripper.org/robert-anderson.htm#

Arthur Ponsonby Moore-Anderson was the eldest son Sir Robert Anderson, K.C.B., LL.D., and Lady Agnes Moore, sister of the 9th Earl of Drogheda. Brought up at the family's London home, 39 Linden Gardens, he was educated at The Leys School and Trinity College, Cambridge. A talented physician, he worked at the London Hospital before travelling to South Africa in 1903. When introduced to Lord Guthrie, the Scottish judge, as the son of Sir Robert Anderson, Guthrie exclaimed: 'Oh, but he is a pioneer!' (A. P. Moore-Anderson 1919, p. 26).

Sharing his father's sense of public service, Moore-Anderson assisted in founding the Cape Town Naval Cadet Corps. During the First World War he served in German East Africa as a Captain in the South African Medical Corps, and was twice mentioned in despatches (London Gazettes, 25 September 1917 and 7 March 1918 refer).

In 1909 he married Charlotte, daughter of William Sloan, of Helensburgh in South Africa. They had two daughters and settled in Cape Town; sold with copied M.I.D. confirmation.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£5,800