Auction: 18002 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 511

Convey to the crews of 44 and 97 Squadrons who took part in the Augsburg raid, the following: the resounding blow which has been struck at the enemy’s submarine and tank building programme will echo round the world. The full effects of his submarine campaigns cannot be immediately apparent, but nevertheless they will be enormous. This gallant adventure penetrating deep into the heart of Germany in daylight and pressed home with outstanding determination in the face of bitter and unforeseen opposition takes its place amongst the most courageous operations of the war. It is moreover yet another fine example of effective cooperation with the other services by striking at the very sources of the enemy effort. The officers and men who took part, those who returned and those who fell, have indeed served their country well.’

Air Marshal A. T. ‘Bomber’ Harris’s summary of the famous daylight strike on Augsburg in April 1942.

The outstanding Second World War immediate D.S.O., immediate D.F.C. and immediate Bar, A.F.C. group of nine awarded to Wing Commander E. E. ‘Rod’ Rodley, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, one of just seven such combinations of gallantry awards won by the R.A.F. in the last war

A long-served pilot of No. 97 Squadron, who often acted as Marker in Path Finder Force operations, Rodley amassed an impressive tally of 76 operational sorties, among them the famous attack on Peenemunde in August 1943

He was already a veteran of two equally famous strikes, the first of them Operation “Margin”, the daring low-level daylight strike on the M.A.N. diesel factory at Augsburg in April 1942 - in which Squadron Leader J. D. Nettleton won the V.C. – and Operation “Bellicose”, the attack on the old Zeppelin sheds at Friedrichshafen in June 1943, when one of his target indicator bombs blew up in his Lancaster: on both occasions – in the face of intense opposition – he displayed ‘magnificent airmanship’ and coaxed his damaged Lancaster home

Awarded an immediate D.S.O. towards the end of his second operational tour, Rodley added an A.F.C. to his accolades for his services as an Instructor at Warboys and then commenced his third operational tour as C.O. of No. 128 Squadron at Wyton, flying Mosquitos as part of the Light Night Strike Force. It was in this latter role, in the closing months of the war, that he undertook no less than seven trips to the ‘Big City’

In 1946 Rodley commenced a distinguished career in civil aviation, initially as a pilot and instructor for British South American Airways (B.S.A.A.). Following the airline’s takeover by British Overseas Airways Corporation (B.O.A.C.) in 1949, he was actively engaged in the Comet programme - often flying with John Cunningham – and was rewarded with a Queen’s Commendation for Valuable Service in the Air

Distinguished Service Order, G.VI.R., silver-gilt and enamel, the reverse of the suspension bar officially dated ‘1943’, with its Garrard & Co. case of issue; Distinguished Flying Cross, G.VI.R., with Second Award Bar, the reverse of the Cross officially dated ‘1942’ and the reverse of the Bar ‘1943’, with its Royal Mint case of issue and card box of issue for the Bar; Air Force Cross, G.VI.R., the reverse officially dated ‘1945’, with its Royal Mint case of issue; 1939-45 Star; Air Crew Europe Star, clasp, France and Germany; Defence and War Medals 1939-45; Coronation 1953, with its card box of issue; Air Efficiency Award, G.VI.R., 1st issue (Fg. Off. E. E. Rodley, R.A.F.V.R.), together with the recipient’s Queen’s Commendation for Valuable Service in the Air badges (2), silver, the reverses numbered ‘R.D. 847363’, good very fine (11)

D.S.O. London Gazette 30 November 1943. The original recommendation - for an immediate award - states:

‘Squadron Leader Rodley has completed 63 operational sorties, 26 as marker. These have included all the targets of major importance in Germany. He has played a conspicuous part in the Squadron’s participation in the recent major air offensive against Germany, and has taken part in two attacks on Berlin, three on Hamburg and others on Hanover, Munich, Nuremburg and Peenemunde to mention only a few.

As one of the Squadron’s most capable and experienced captains he has been selected regularly for special tasks which he could always be relied upon to carry out successfully.

At all times his spirit, courage and resourcefulness has set a fine example to the Squadron.’

D.F.C. London Gazette 28 April 1942. The original recommendation - for an immediate award - states:

‘Flying Officer Rodley took part in the attack on the Diesel factory at Augsburg. This flight entailed a daylight crossing of enemy occupied territory of a total of approximately 900 miles.

Flying Officer Rodley was acting as reserve before take-off. One aircraft failing, he was called on to take part in the operation. In spite of the fact he knew his oil pressure gauge was out of action, he started the flight. On reaching the target his Leader was shot down in flames. Nevertheless, he carried out a very low-level attack in the face of intense and accurate anti-aircraft fire and dropped his bombs directly on the main building of the target.

Throughout the whole operation, Flying Officer Rodley showed the greatest determination and valour.’

Covering remarks:

‘This officer made his attack with great skill and resolution and by magnificent airmanship brought his disabled aircraft and crew back to base after it had been rendered unairworthy and unbattleworthy by enemy action.’

Bar to D.F.C. London Gazette 17 August 1943. The original recommendation - for an immediate award - states:

‘This officer took part in the raid on Friedrichshafen. He was one of the two aircraft detailed to act as marker. This entailed visually identifying the target and indicating it for the main force.

The defences were heavy and being the first aircraft over the target they were singled out for individual attention. Nevertheless Flight Lieutenant Rodley pressed home his attack successfully.

On the way to North Africa, en route from the target, an explosion occurred in the aircraft which, it was discovered, was a target indicator bomb which had hung up. Undaunted, Flight Lieutenant Rodley and crew flew on to base and landed the damaged aircraft safely.

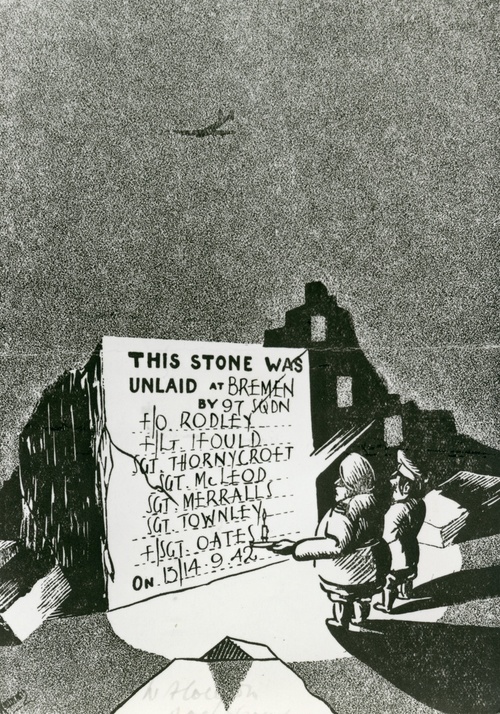

This officer has completed 37 sorties since receiving the D.F.C. for the Augsburg raid on 17 April 1942, and since then his targets have included all the major objectives in the Ruhr and Rhineland, also Hamburg and Bremen.

On all occasions this officer has pressed home his attack with courage, determination and accuracy and he has been an outstanding member of his squadron.’

A.F.C. London Gazette 7 September 1945. The original recommendation states:

‘Squadron Leader Rodley has been employed as Chief Flying Instructor of this unit [Pathfinder Navigation Training Unit] for fifteen months. Throughout this period he has conscientiously fulfilled his arduous duties and has never spared himself in his endeavours to pass on his extensive knowledge to the training personnel. By his untiring efforts a consistently high standard of training has been achieved.’

Queen’s Commendation for Valuable Service in the Air London Gazette 1 January 1953.

Ernest Edward Rodley was introduced to flight by a ‘kindly uncle’ who took him to Croydon, where he was ‘captured for life by a circuit in an Avro 504K’ It was 1926 and he was 12 years of age. He subsequently joined the R.A.F.V.R. in 1937 and undertook pilot training.

‘Wings’ up and newly commissioned, he commenced the Second World War as a flying instructor. But in late 1941, his operational career got off the ground with his appointment to No. 97 (Straits Settlements) Squadron, a Manchester unit. It was the commencement of an outstanding career, a career marked by his participation in some of the most outstanding operations ever undertaken by Bomber Command.

Most notable of his early sorties in 97 Squadron was a strike against the Scharnhorst, Prinz Eugen and Gneisenau in Brest harbour on 18 December 1941, when he ‘bombed successfully’ but was diverted to Mildenhall after a close encounter with an enemy fighter. Shortly afterwards, the Squadron re-equipped with Lancasters and Rodley’s tour continued apace, with trips to Hamburg and Essen.

Disaster nearly struck in poor flying conditions on the night of 20 March 1942, when, after taking-off on a ‘gardening’ sortie laden with six mines, and 2,000 gallons of high octane fuel, the starboard wing of Rodley’s aircraft struck a rooftop in Boston, Lincolnshire. Grappling with his controls and too low to order a bale out, Rodley somehow coaxed his damaged aircraft to a forced landing on a sandbank on Freiston Sands. But for his coolness and skill, the population of Boston would have suffered a holocaust; many years later, when his name he was formally thanked by the townspeople.

Operation “Margin” - The Augsburg Daylight Raid, 17 April 1942 – Immediate D.F.C.

Next up, however, was an operation of a very different nature, for the R.A.F.’s newly delivered Lancasters were deemed capable of undertaking daylight operations of a precision nature. The result was Bomber Command Operation Order No. 143, which proposed long-range, low-level, precision strikes which should, it concluded, ‘cause considerable alarm and despondency among the population who at present may consider themselves outside the danger area’.

Thus was born Operation “Margin”, an immensely daring – even suicidal – undertaking to attack the M.A.N. Diesel Factory at Augsburg, in deepest Bavaria, a major producer of diesel engines for German U-boats. Two squadrons were assigned to the operation, Rodley’s 97 at Woodhall Spa, led by Squadron Leader John Sherwood, D.F.C., and 44 Squadron at Waddington, led by Squadron Leader John Nettleton. Each squadron was to contribute six Lancasters to the attacking force and to hold another aircraft in reserve.

A busy round of low-level, long distance practice flights having been undertaken in the first half of April 1942, the chosen aircrew were called to top secret briefings at Woodhall Spa and Waddington; up until that time, senior planning staff aside, only the formation leaders were aware of the exact target.

Rodley – in typically modest form – takes up the story: ‘When the curtain drew back at the briefing there was a roar of laughter instead of a gasp of horror. No one believed that the Air Force would be so stupid as to send 12 of its newest four-engined bombers all that distance inside Germany in daylight. We sat back and waited calmly for someone to say “Now the real target is this.” Unfortunately, it was the real target, a factory near Augsburg that was a major manufacturer of diesel engines for submarines.’

But as Rodley concluded – however insane the mission – ‘it was touch and go in the North Atlantic between Britain having enough to eat and not having enough to eat’, so the crews were determined to play their part in preventing these diesel engines ever getting near a U-boat.

Of subsequent events enacted on 18 April 1942, much has been written, not least because of the high calibre of gallantry displayed by all concerned. John Nettleton’s two 44 Squadron formations were pounced by enemy fighters over France and all but blown out of the sky. Just his and one other aircraft made the target – ahead of 97 squadron - but his was the only one to make it home. He was awarded the Victoria Cross; see The Air VCs by Chaz Bowyer, for full details.

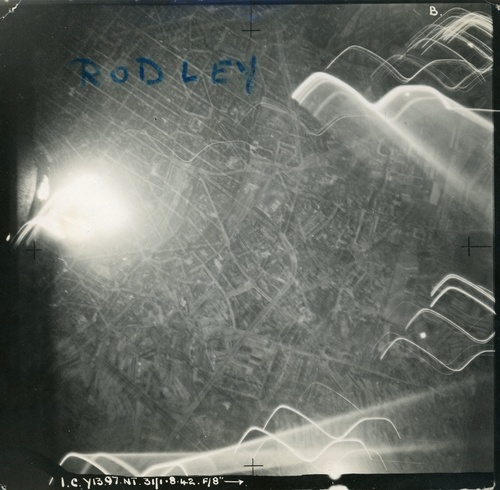

Rodley and 97 Squadron fared a little better, having taken a different course over France and avoided fighter interception. But what awaited them over the target at Augsburg was a fully alerted enemy. Rodley’s last minute decision to place a tin helmet under his vital parts on the pilot’s seat proved a sensible one, for as they roared in at 50 feet over the target the flak was relentless.

In his own words – patently very modest words – Rodley later described the raid in the following terms:

‘The route took us low, at about 100 feet, down to the south coast, across the Channel. We were to join No. 44 Squadron at the south coast, six aircraft from each squadron, and we were to go as a formation of 12 the rest of the way. We saw 44 Squadron slightly ahead of us, but we realised that they were drifting to port, and we continued in the direction we should have been going. Our six aircraft pressed on very, very low across the Channel so that we were underneath the radar. I could see the sandbanks of France coming up ahead of us. We had no opposition at all crossing the defended coast. We proceeded south of Paris where I saw the second enemy aircraft I saw during the whole war. It was probably a courier - a Heinkel 111. It approached and, recognising us, did a 90-degree bank turn back towards Paris. We continued flying on at 100 feet. Occasionally you would see some Frenchmen take a second look and wave their berets or their shovels. A bunch of German soldiers doing P.T. in their singlets broke hurriedly for their shelters as we roared over. The next opposition was a German officer on one of the steamers on Lake Constance firing a revolver at us. I could see him quite clearly, defending the ladies with his Luger against 48 Browning machine-guns. Our route took us from the north end of Lake Constance across another lake, where we turned north towards the target. We hadn’t seen a thing on the way of the German Air Force. We were belting at full throttle at about 100 feet towards the targets. I dropped the bombs along the side wall. We flashed across the target and down the other side to about 50 feet, because flak was quite heavy.

As we went away I could see light flak shells overtaking us, green balls flowing away on our right and hitting the ground ahead of us. Leaving the target I looked down at our leader’s aircraft and saw that there was a little wisp of steam trailing back from it. The white steam turned to black smoke, with fire in the wing. I was slightly above him. In the top of the Lancaster there was a little wooden hatch for getting out if you had to land at sea. I realised that this wooden hatch had burned away and I could look down into the fuselage. It looked like a blow lamp with the petrol swilling around the wings and the centre section, igniting the fuselage and the slipstream blowing it down. Just like a blow lamp. He dropped back and I asked our gunner to keep an eye on him. Suddenly he said, “Oh God, Skip, he’s gone. He looks like a chrysanthemum of fire.” One other of our aircraft caught fire just short of the target, but kept on, dropped the bombs and then crashed. The raid was suicidal. Four from 97 Squadron got back, but only one from 44 Squadron. Five out of twelve.’

Rodley’s leader, Squadron Leader John Sherwood, was also recommended for the V.C. and, as with the recommendation for Nettleton’s award, it was endorsed by ‘Bomber’ Harris. But a subsequent annotation ordained that he was ‘to be recommended for D.S.O. if later found to be alive.’ Miraculously, Sherwood was indeed found alive, having been thrown clear of his burning Lancaster still strapped to his pilot’s seat, and he received said D.S.O. The rest of his crew were perished. Warrant Officer Tom Mycock, also of 97, continued to fly his Lancaster to the target, even though it was ‘a ball of fire’: many considered his deeds were equally worthy of a V.C. recommendation.

For his own part, Rodley was awarded an immediate D.F.C.

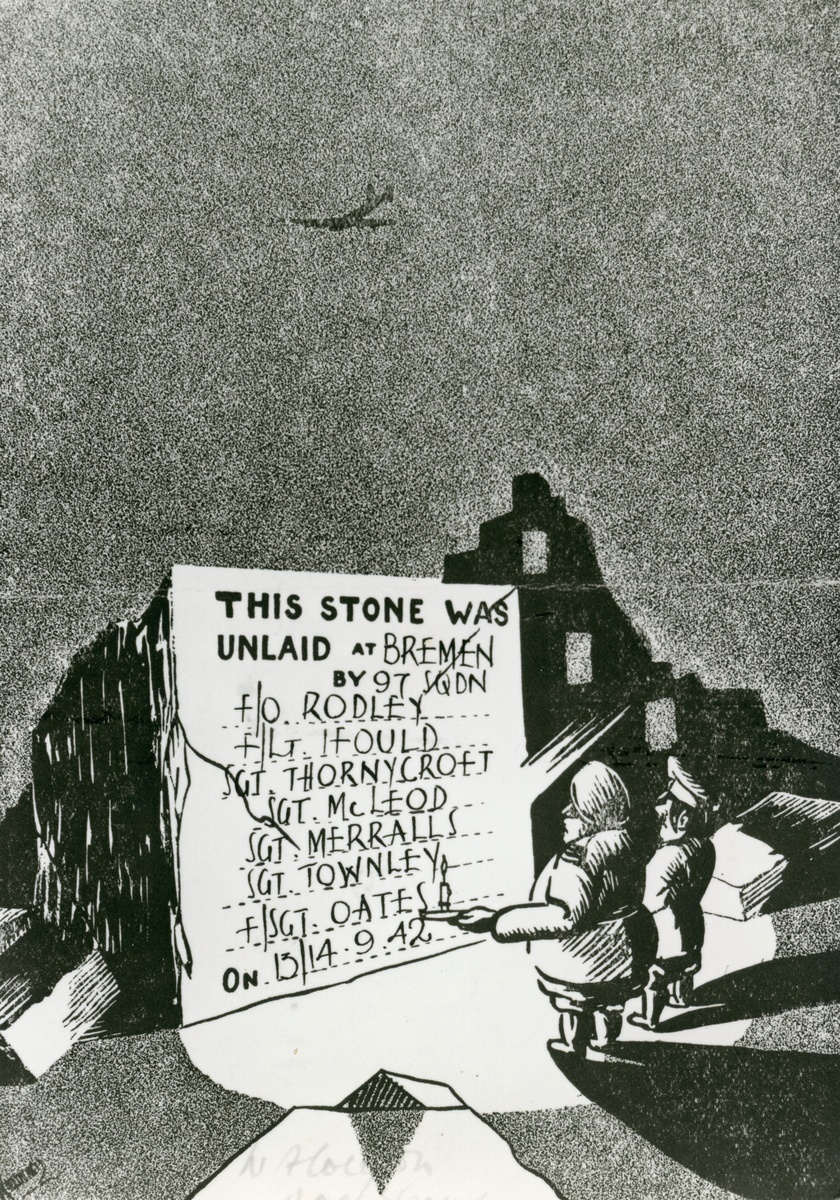

He went on to complete his first tour of operations in September 1942. Multiple trips to Essen, Cologne, Dusseldorf and Hamburg aside, it is worth stating for the record that he was assigned to Bremen on no less than five occasions during this tour, on each occasion noting ‘much heavy flak’. In deed Rodley and his crew encountered their fair share of flak, the Squadron O.R.B. noting his aircraft’s forward Perspex was holed over Duisberg on the night of 23-24 July 1942.

In a sortie to Hamburg later in the same month, he noted in his report: ‘As we approached the target about 60 searchlights caught and held us for about 10 minutes in spite of vigorous evasive action. Heavy accurate flak burst close to us, causing our starboard outer engine to fail and damaging the airframe.’

Operation “Bellicose” – The Friedrichshafen Raid, 20 June 1943 – Immediate Bar to D.F.C.

Having returned to the operational scene in April 1943 – again with 97 Squadron – Rodley regularly found himself visiting old haunts such as Cologne, Dusseldorf and Essen. The Squadron was now a unit of the Path Finder Force and marking duties were high on the agenda.

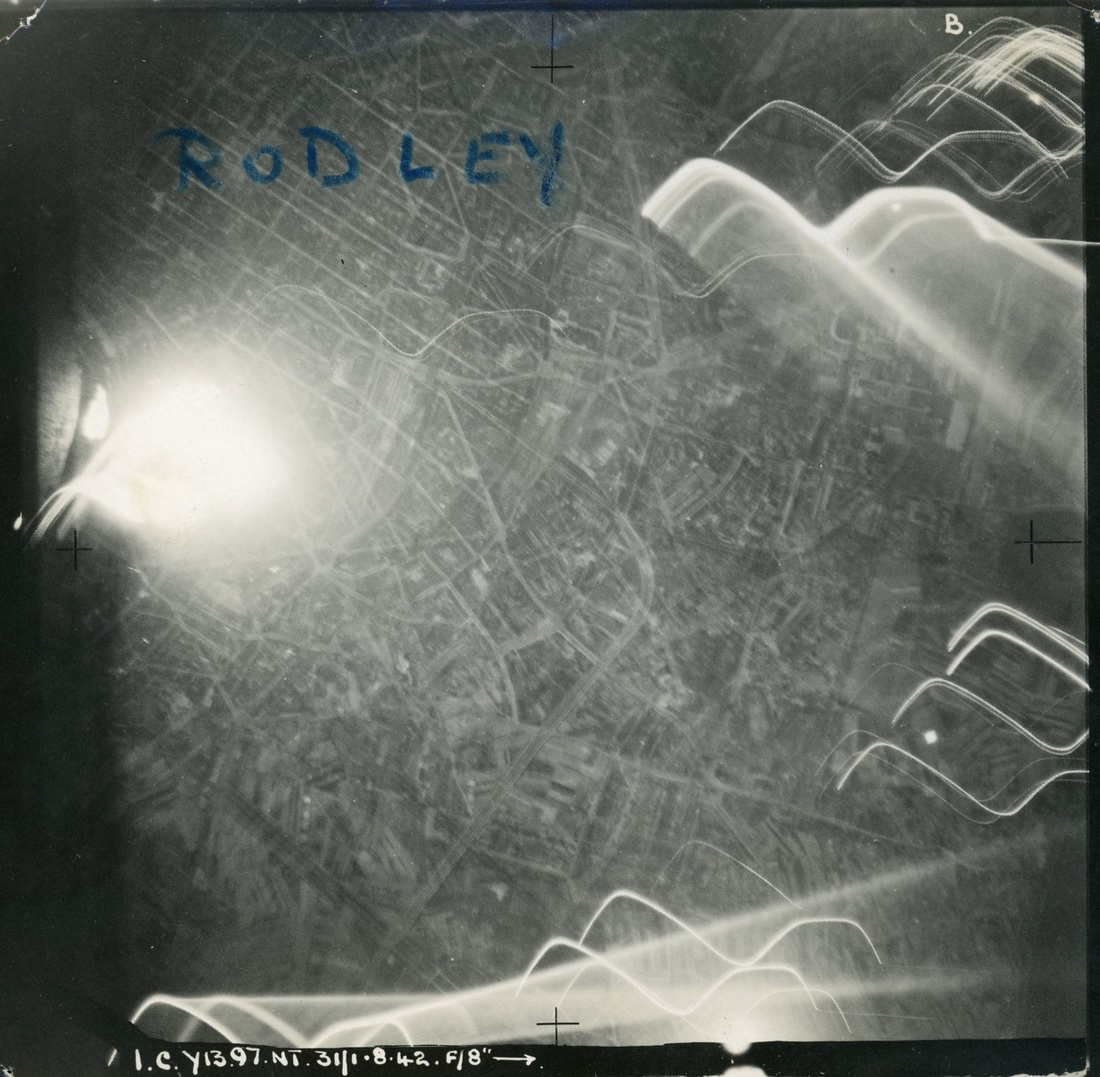

Rodley was to perform just such duties during yet another Bomber Command epic – the strike on the old Zeppelin sheds at Friedrichshafen on 20 June 1943; the sheds were being used for the manufacture of Wurzburg radar sets.

Four Lancasters of 97 Squadron were selected for Pathfinder duties, leading in a larger force from No. 5 Group. When the precision strike was over – and to confuse and disappoint awaiting enemy night fighters - the participating aircraft were detailed to fly straight on over the Alps to North Africa. It was a brilliant tactical plan and it met with total success. That success was largely due to the highly accurate marking work of Rodley and his crew. Last of the Lancasters, by Martin Bowman, sets the scene:

‘The weather at the target was clear, with Lake Constance and the surrounding area bathed in bright moonlight, which enabled the Pathfinders to place their markers very close to the target. Circling Friedrichshafen the crews awaited instructions from the Deputy Leader. Both attacking elements has been briefed to bomb visually from 5,000 feet. There were approximately sixteen to twenty heavy flak guns and 18-20 light flak guns and about 25 searchlights, all within a radius of about six to eight miles of the target. They were more active than expected … ’

Pilot Officer D. I. Jones, D.F.C., a fellow 97 Squadron marker, takes up the story over the target:

‘Rod Rodley turned over Lake Constance, headed directly between our rows of flares and strained every nerve to drop the target marker before Johnny Sauvage could make it. The factory was plainly visible when Rod opened his bomb doors. His bomb aimer released a target marker only to see a green cascade burst slightly ahead of the shed roofs. Johnny Sauvage had beaten him to it after all. Rod Rodley then became aware for the first time of the intensity of the flak, but still managed to swing about to release more target markers. I followed suit … within seconds high explosive bombs from No. 5 Group high above came crashing down on our markers. Concussions from the resulting explosions added to our discomfort, and I was forced to abandon one run in to the target because it was impossible to hold my aircraft on an even keel … Eventually it was time to leave the smouldering ruins of our target and a course to steer was given me by Pilot Officer Jimmy Silk, my dour and utterly reliable Scots navigator … ’

Job done.

But Jones continues:

‘All the Lancasters except one had an uneventful journey before landing at either Maison Blanche or Blida airfields. The odd one out was Rod Rodley’s aircraft. For him and his crew it was far from a peaceful flight to North Africa. As he slowly descended over the Mediterranean, a lurid red glow suddenly blossomed below his Lancaster. Cursing violently Rod took evasive action, obviously thinking that a night fighter or a convoy has spotted him. His flight engineer, Sergeant J. Duffy, set off on a tour of inspection and found the bomb bay a mass of flames. The damage, however, had not been caused by a night fighter or flak from a convoy but from a target marker which had failed to drop over the target and had ignited when its barometric pressure fuse operated at a pre-set height. Rod pulled the jettison toggle and was vastly relieved to see the deadly ball of fire drop away into the sea below.’

He was awarded an immediate Bar to his D.F.C.

Hamburg, Peenemunde and beyond – Immediate D.S.O.

Post-Fredrickshaven, Rodley flew another 20 sorties to complete his second operational tour, including a brace of trips to the ‘Big City’ and three to Hamburg at the time of the famous ‘firestorm’ raids in July-August 1943.

He was also present in the famous attack mounted on Peenemunde on 17-18 August 1943, when he acted as a back-up Marker and - unknown to the A.O.C. - embarked as his 2nd Pilot Group Captain C. D. C. ‘Bruin’ Boyce, the S.A.S.O. of No. 8 Group. According to Boyce, he decided to go on the raid himself because ‘it was something special’. He asked 97’s C.O. to find him ‘a reliable pilot’, so the latter’s choice fell upon Rodley.

Rodley’s tour continued through until October 1943, by which time he had also attacked Hanover, Mannheim, Munich, Nuremburg and Stuttgart. With 63 sorties to his credit, he was award an immediate D.S.O.

Third operational tour – C.O. of No. 128 Squadron

After a successful spell at R.A.F. Warboys as an instructor – for which he was awarded the A.F.C. – Rodley took command of No. 128 Squadron at Wyton in February 1945.

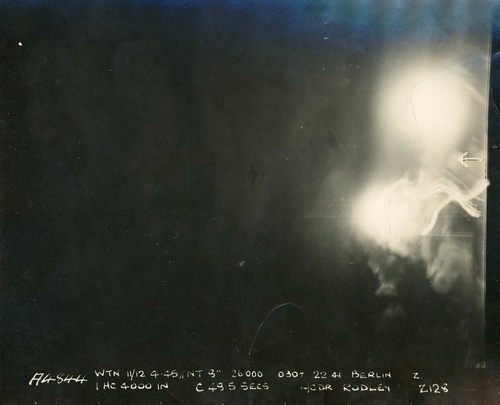

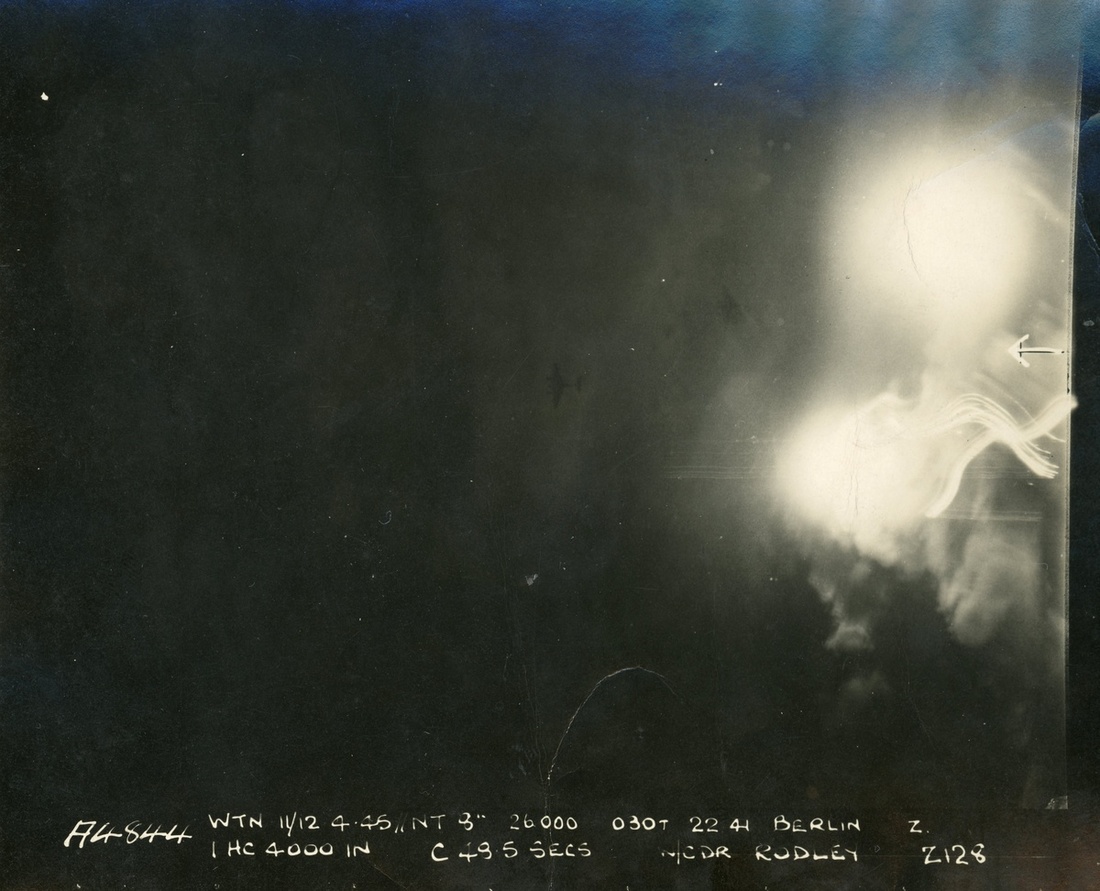

The unit operated in Mosquitos as part of the Light Night Strike Force and Rodley completed another 13 sorties, seven of them to the ‘Big City’; on just such a trip on the night of 24-25 March 1945, his Mosquito was ‘coned on the run-in’ and damaged.

Other targets visited in his third operational tour included Erfurt, Magdeberg and Kiel.

Civil Aviation - Queen’s Commendation for Valuable Service in the Air

In September 1945 - at the behest of his ex-Pathfinder boss Air-Vice Marshal Don Bennett - Rodley was seconded as a pilot and instructor to British South American Airways (B.S.A.A.) at Heathrow. A state-run airline in the United Kingdom in the late 1940s, B.S.A.A. was responsible for services to the Caribbean and South America. At the time of Rodley’s arrival it was based at Heathrow – in tents – and operating on Lancastrians. He remained similarly employed after being demobbed in July 1946.

The company was merged with British Overseas Airways Corporation (B.O.A.C.) at the end of 1949 and, in March of the following year, Rodley was ‘checked out’ on the new Comet jet airliner by John Cunningham and became the world’s first jet endorsed Airline Transport Pilots Licence holder. He subsequently gained appointment as Officer-in-Charge of Training of the Comet Fleet and was awarded the Queen’s Commendation for Valuable Service in the Air.

Rodley enjoyed a long career with B.O.A.C., finally retiring as a Boeing 707 Captain in 1968. He flew the Beatles to Florida, via New York and was rewarded with a signed in-flight menu; see next Lot.

Latterly a pilot for Olympic Airways, Rodley is credited with amassing an amazing 28,000 flying hours. He died in 2004.

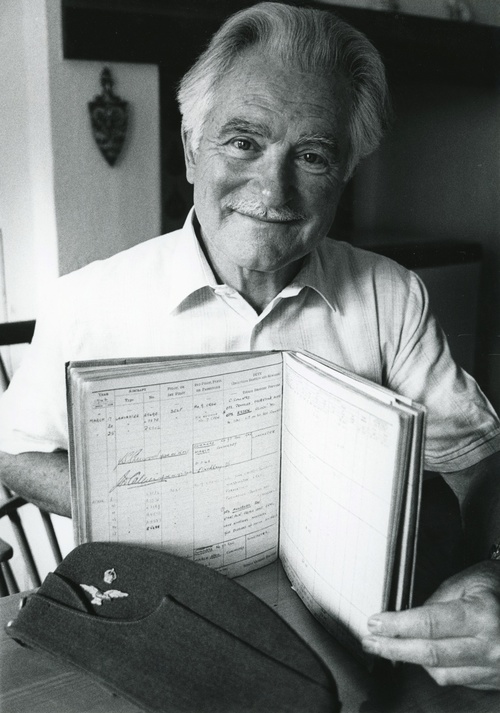

Sold with an archive of original documentation and photographs, comprising:

(i)

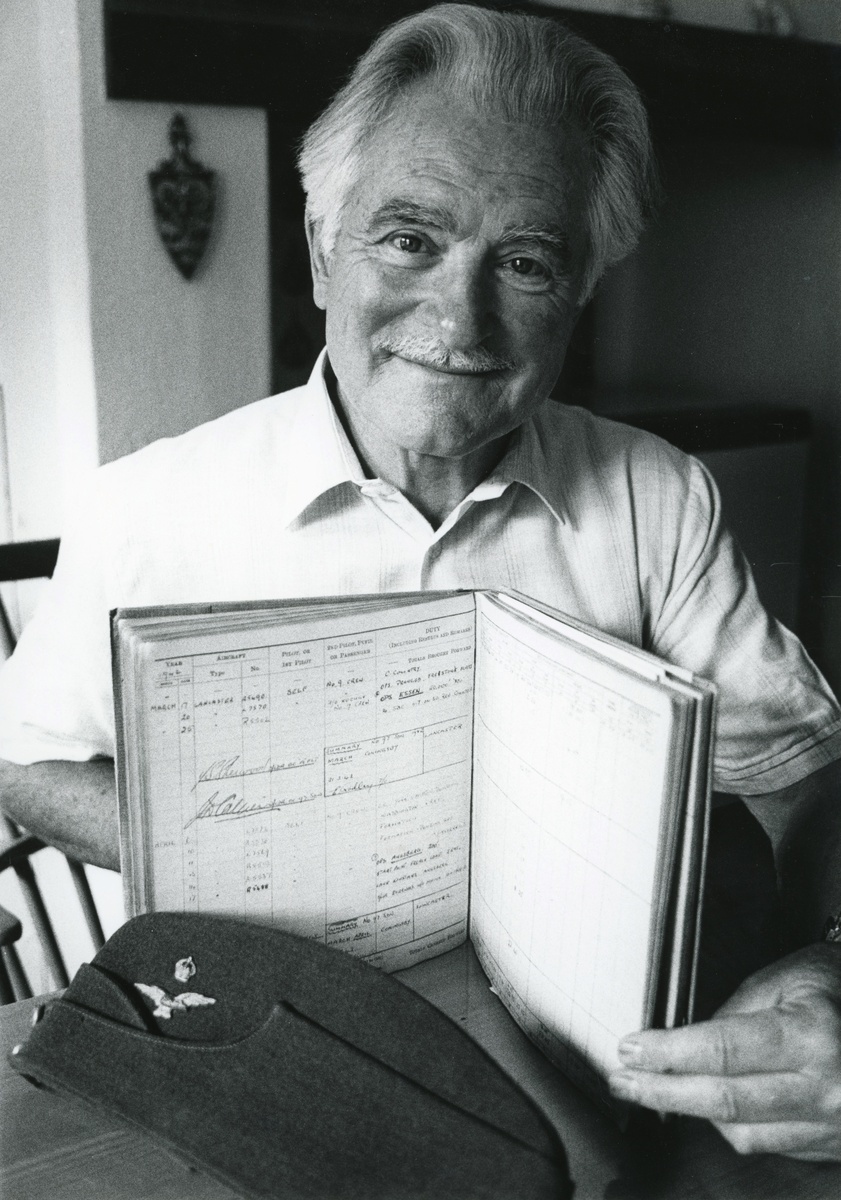

The recipient’s original R.A.F. Pilot’s Flying Log Books (Form 414 types) (2), covering the periods May 1937 to April 1941, and April 1941 to September 1945, thus a full record of his R.A.F. career, and with additional civil aviation entries for 1946-51, including flights with John Cunningham on Comets; a section of several pages cut-out in November 1949, but the entries remaining continuous.

(ii)

Original R.A.F. Path Finder Force Certificate awarding the P.F.F. Badge to ‘Acting Squadron Leader E. E. Rodley, D.F.C., 61472’, dated 23 October 1943; together with a Pathfinder Association dinner menu, dated 7 May 1954, bearing the signature of Arthur T. Harris.

(iii)

A Postagram from Air Chief Marshal Harris, dated 1 August 1943, offering his warmest congratulations on the award of the First Bar to the D.F.C., in original O.H.M.S. envelope of transmission; two further letters from the Chairman and Head of Central Staff Department at Imperial Chemical Industries Ltd, offering similar congratulations and a telegram to Rodley at St John’s, Redhill, Surrey, from John Crutch, 5 June 1942: ‘Congratulations, keep on dropping them, still going up and down and enjoying life, cheers’, and a newspaper clipping from The Sunday Times, dated 28 November 1943, announcing the award of his D.S.O.

(iv)

A comprehensive photograph album including some outstanding portrait photographs in uniform, cockpit images and formal flight crew images; further images of an R.A.F. dance and aircrew enjoying time off ops; post-war colour reunion photographs, approximately 65 photographs in totoal, a number hand annotated with the names of aircrew; together with approximately 15 post-war commemoration service photographs, the majority taken in the 1980s.

(v)

A booklet with the recipient’s old training notes, together with ‘No. 2 Group Line & Rumble Book’, with extensive entries for the period September 1939 to July 1940.

(vi)

An illuminated scroll from the Probus Club of Boston, Lincolnshire, dated 28 August 1975, as presented to Rodley to mark the occasion he avoided a serious calamity by crash-landing his mine-laden aircraft on Freiston Sands on 20 March 1942, framed and glazed; together with a town crest and related letter.

(vii)

Two hand written manuscripts, being the recipient’s extensive notes for two speeches, together with a further mss. with extensive wartime coverage for an interview with the author Ralph Barker.

(viii)

A considerable archive of correspondence between Rodley and a number of aerospace authors, notably Hamish Mahaddie, Barry Blunt and Martin Middlebrook; further correspondence with the Bomber Command Association & P.R.O.

(ix)

Books and pamphlets relating to aviation (6): a hardback copy of The Lancaster at War, by Garbett & Goulding; Bomber Command’s Offensive against the Axis, September 1939 – July 1941, H.M.S.O.; Bombing Sense, A.M. Pamphlet 139, published September 1942; Air Sea Rescue, issued by the Ministry of Information, H.M.S.O., 1942; The Hawker Hart, No. 57, & The Avro Lancaster I, No. 65, published by Profile Publications; together with the recipient’s printed Air Council’s Pilot’s Notes for the Mosquito and Lancaster.

(x)

An archive of modern newspaper articles, including the ‘Lancaster Legend’ published by the Lincolnshire Echo, 7 April 1997; a copy of the Surrey Advertiser with a detailed and poignant article by Rodley paying tribute to the men of R.A.F. Waddington who died in the Augsburg Raid, dated 15 May 1992.

(xi)

A letter of thanks from Peter Duncan of the B.B.C., regarding his taking part in ‘In Town Tonight’ and performing an excellent broadcast, dated 31 December 1951; together with a DVD titled ‘The Pilots’, a B.B.C. broadcast of 5 March 1963, which features Rodley.

(xii)

Royal Mail First Day Covers (4): Appointment to the Distinguished Service Order, Jersey, 12p, 12 October 1984; The Award of the Air Force Cross, Jersey, 13p, 10 April 1984; The 30th Anniversary of the First Flight of the Comet, Jersey, 11p, 27 July 1979, bearing the signature of Group Captain John Cunningham; A Commemoration of the 35th Anniversary of the Augsburg Raid, 9.5p, 17 April 1977.

Also sold with a selection of related artefacts, comprising:

(i)

The recipient R.A.F. officer’s side-cap, with ‘Rodley’ in ink to interior lining.

(ii)

A pair of painted, metalled squadron crests for 97 and 128 Squadrons, for wall display.

(iii)

A wooden door plaque, with painted inscription, ‘128 Squadron, Officer Commanding, W./Com. E. E. Rodley, D.S.O., D.F.C.’

(iv)

A commemorative plate for the Berlin Airlift.

(v)

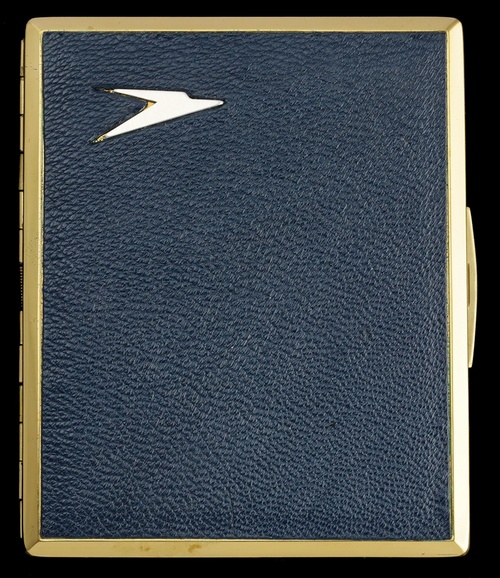

A pair of ‘E.R.’ cuff links, gold and enamel, in Plante, Bond Street, London leather case, as presented to the recipient by the Queen Mother.

(vi)

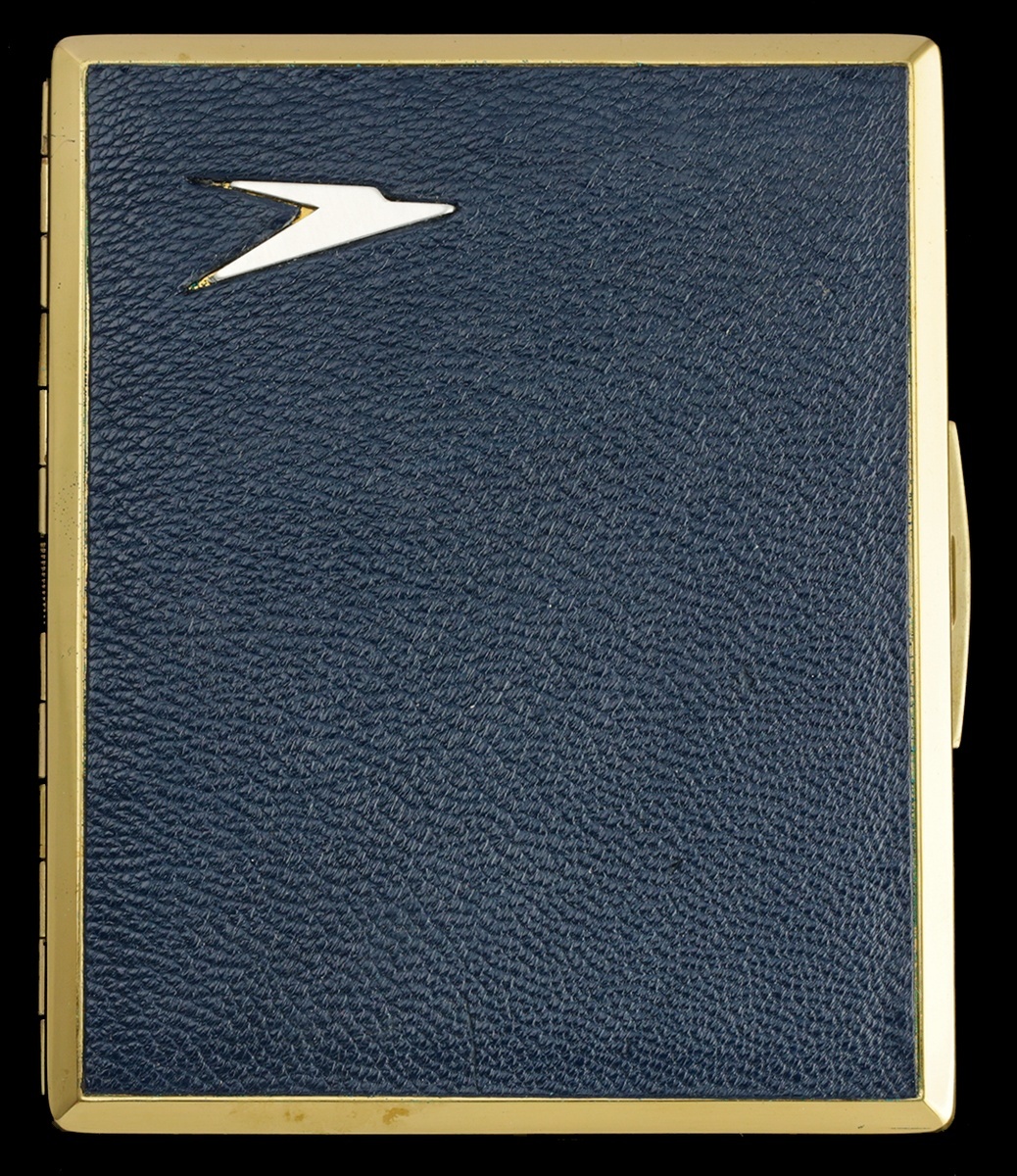

A presentation ‘Comet’ cigarette case, gilt metal, the interior inscribed, ‘B.O.A.C. COMET 4 New York-London, October 4, 1958, First Transatlantic Pure Jet Service.'

Please see Lot 602A for the recipient's miniature dress medals.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£19,000