Auction: 18002 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 478

THE ROAD TO SUFFRAGE - A CENTENARY (1918-2018)'The happiest people I have known have been those who gave themselves no concern about their own souls, but did their uttermost to mitigate the miseries of others.'

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815-1902), a leading figure of the women's rights movement.

This year marks the 100th Anniversary of a number of important events, high on the list being the foundation of the Royal Air Force on 1 April 1918 and the signing of the Armistice on 11 November 1918. Yet another landmark event took place in November 1918: the signing of the Qualification of Women Act on the 21st.

It had been the Great Reform Act of 1832 and the Municipal Corporations Act of 1835 that effectively barred women from voting. Their cause had been supported, albeit in a very informal manner, from the start but no real headway was achieved over the coming decades. It took until the 1860s for the first societies to generate discussion into the role of women in civil affairs. One of them, the Kensington Society, was founded in 1865, and numbered Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon (1827-1891) among its early members. But subsequent attempts to gather signatures in support of amendments to the Acts of Parliament came to no avail.

Until 1903, the women's movement was purely focussed upon working towards change through the constitution. This would quickly change with the arrival of the Women's Social and Political Union (W.S.P.U.) on the scene, when the suffragist was replaced with the suffragette. The faction - controlled by the powerful Pankhurst sisters - mobilised supporters on large marches. Whilst the political sphere generally approved of women's right to vote, the Liberals saw no future in the Act and blocked any vote in the House. Militancy grew.

Soon the Union had three arms in which they might promote the cause:

- Civil Disobedience

- Destruction of Public Property

- Arson or Bombings

In Northern Ireland, Lilian Margaret Metge, the grand-daughter and widow of Members of Parliament, proved to be a particularly keen exponent of the W.S.P.U.'s chosen path, notching up what might be termed a 'home run' after participating in all of the above activities. In fact, as leader of 'The Brutes' in Ireland, she rightly accepted as one of, if not the most active militant Irish suffragette in history.

Just such activities put the Suffragettes firmly in the public eye; the movement was spreading, and fast, propelled forward by mass marches. Arrests were occurring on a daily basis and resultant hunger strikes added to the publicity, so much so that the Government passed the highly unpopular 'Cat and Mouse' Act of in 1913; this the year in which Emily Davison was killed, after throwing herself at the King's horse on Derby Day. Then in March 1914 Mary Richardson slashed the Rokeby Venus and Mrs. Pankhurst led a march to the gates of Buckingham Palace on 21 May - only to face a police baton and see 67 of her supporters arrested, Lilian Metge among them.

With the outbreak of World War One, the struggle was officially ceded on 14 August 1914. Many suffragettes subsequently lent valuable service at home and abroad. Nonetheless, the true road to equality was not finally paved until 1928, with the introduction of the Equality of the Representation of the People Act.

In this, the 100th Anniversary year of that Act, we are pleased to offer the rare 'Medal of Valour' awarded to Lilian Metge, likely one of the last such awards ever made by the W.S.P.U.

'Gentlemen, I know what it is. There is one law for women and another for men. A woman could not get justice here. I'm going home.'

A forthright Lilian Metge speaks her mind in the dock at Lisburn Courthouse, 8 August 1914.

The historically important Women's Social and Political Union Medal for Valour awarded to Mrs. Lillian Metge, a veteran of the 21 May 1914 march to the gates of Buckingham Palace

It was, however, her subsequent part as a ringleader of 'The Brutes' back in Ireland that gained her lasting notoriety: they bombed Lisburn Cathedral on 31 July 1914. But for the cessation of Suffragette activities in the following month, her resultant incarceration - and hunger strike - may have been of longer duration

Women's Social and Political Union Medal for Valour, silver, 22mm, the obverse inscribed 'Hunger Strike', the reverse inscribed 'Lillian Margaret Metge', hallmarks for Birmingham 1914, the suspension bar engraved, 'August 10th 1914', upper brooch bar inscribed 'For Valour', the reverse with maker's name 'Toye, 57 Theobalds, Rd. London', with original silk ribbon, generally good very fine and excessively rare, housed in an old H. T. Lamb, St. John's Square, Clerkenwell, London purple leather case

Provenance:

Acquired by the present owner during the 1980s.

Lillian Margaret Metge was born in 1870, the daughter of Richard Grubb of Cahir Abbey, County Tipperary and Killeaton House, County Antrim. Her grandfather was Jonathan Richardson of Glenmore, Liberal Member of Parliament for Lisburn, 1857-63, and she was the second husband of Captain Robert Henry Metge, who died in 1900, having himself been the Member of Parliament for Meath.

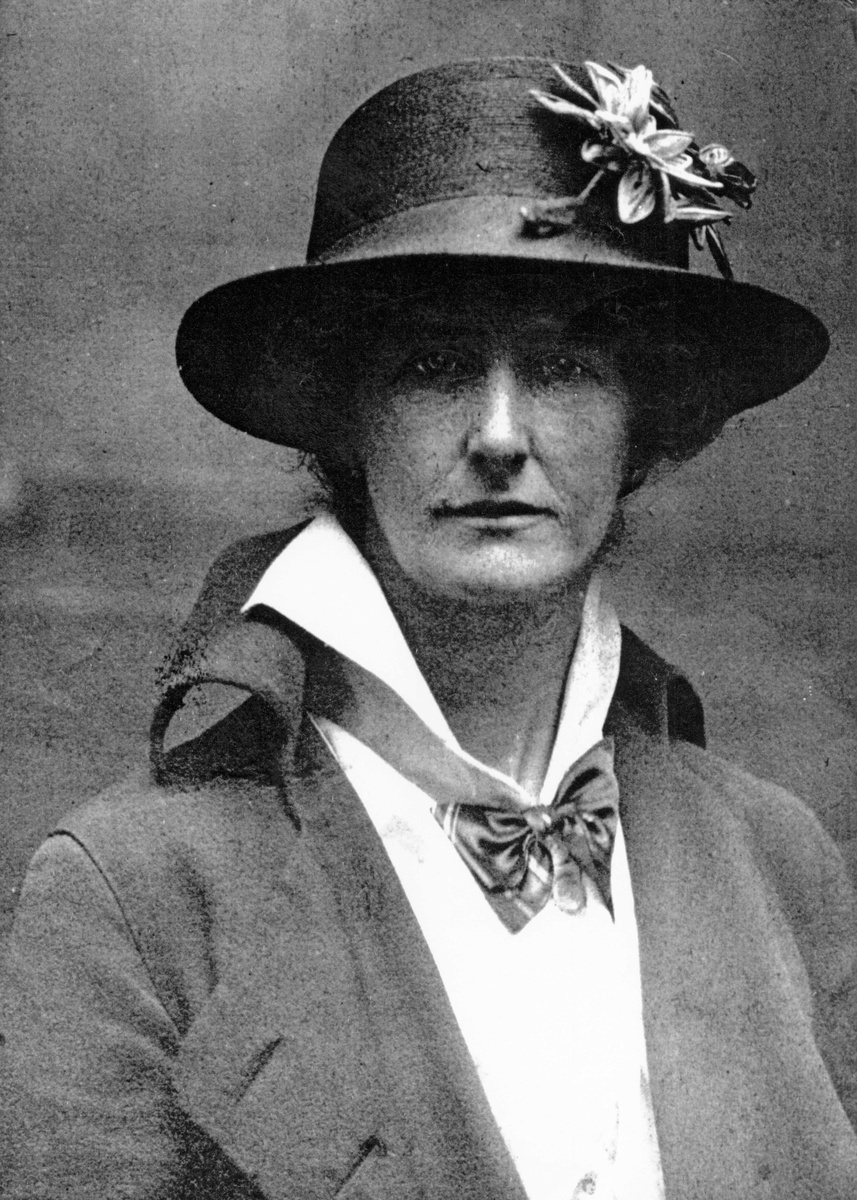

Described as a 'tall, straight-backed and stern' woman, Metge appears to have become increasingly involved in the women's movement following the loss of her husband. The suffrage movement in England was essentially represented by the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (N.U.W.S.S.), the constitutional arm, and the Women's Social and Political Union (W.S.P.U.), the militant arm. In Ireland, the Irish Women's Franchise League (I.W.F.L.) was founded in 1908 by Hanna Sheehy Skeffington and acted mainly through its publication, The Irish Citizen. An attempt was subsequently made to unite the movement in Ulster, thus a joining of forces with the Irish Women's Suffrage Federation (I.W.S.F.). The latter had been formed by Metge and L. A. Wallington in 1910; Metge onetime served as President and Secretary of Federation.

By 1912, Metge - 'an active and able agitator' - was becoming the leading voice of Irish suffrage, representing the I.W.S.F. at the International Women's Congress at Budapest and regularly reporting for The Irish Citizen. In April 1914, however, she resigned her membership of both the Lisburn Suffrage Society and I.W.S.F., for she had been joined in Ireland by Dorothy Evans of the W.S.P.U. and intended to play a more militant role. That intention was perhaps echoed in her parting words to the I.W.S.F.:

'I have never done a militant act but whatever the future may hold the only possible dishonour would be in having seen the vision yet turned back.'

Metge was subsequently among the 200-strong W.S.P.U. deputation of the W.S.P.U. that attempted to charge Buckingham Palace on 21 May 1914. Kate Fry, a witness to the events, wrote in her diary:

'In the afternoon I went to Buckingham Palace to see the Women's deputation - led by Mrs. Pankhurst which went to try and see the King. It was simply awful - oh! Those poor pathetic women - dresses half torn off - hair down, hats off, covered with mud and paint and some dragged along looking in the greatest agony.

But the wonderful courage of it all. One man led along - collar torn off - face streaming with blood - he had gone to protect them. Fancy not arresting them until they got into that state. It is the most wicked and futile persecution because they know we have got to have 'Votes' - and to think they have got us to this state - some women thinking it necessary and right to do the most awful burnings etc. in order to bring the question forward.

Oh what a pass to come to in a so-called civilised country. I shall never forget those poor dear women.

The attitude of the crowd was detestable - cheering the police and only out to see the sport. Just groups of women here and there sympathising, as I was. I saw Mrs Merivale Mayer, Miss Bessie Hatton and a good many women I knew by sight. I stayed until there was nothing more to be seen. The crowds were kept moving principally by the aid of a homely water cart. It was very awful.

Mrs. Pankhurst herself was arrested at the gates of the Palace. I did not see her but she must have passed quite close to me. I went to Victoria and had some tea and tried to get cool, but I felt very sick. The King could have done something to prevent it all being so horrible - he isn't much of a man.'

Metge was one of 67 who were arrested on that day, no doubt having faced Police batons by the gates of the Palace. Her resolve was far from broken: 'I see now how militants are made.'

In July she was again arrested, back in Belfast for the trial of Evans and Muir, during which Metge was caught smashing windows at the courthouse. Evans herself was imprisoned and went onto hunger strike, being discharged on medical grounds to the care of Metge and other friends on 26 July 1914.

A bigger plan had clearly been afoot for some time, for their most infamous act took place in the very early hours of 31 July. The Ulster Echo takes up the story:

'Shortly after two o'clock this morning an explosion occurred in the Church of Ireland Cathedral, Lisburn, wrecking a large stained glass window and tearing a hole in the floor. The Police, attracted by the noise discovered a quantity of Suffragette literature. A later message states that directly underneath the large stained-glass window of the church a fairly large hole was discovered, while on the ground were fragments of masonry and broken glass scattered about. Each section of the window, from the sill to the top, bore evidence of the shock. The window is believed to be at least 300 years old.'

Soon after Metge - together with Evans, Carson and Wickham - was arrested on suspicion of the crime. None gave a statement having been charged and cautioned. A mob had gathered outside her house on Seymour Street, hurling both abuse and missiles when the leader of 'The Brutes' and her three accomplices were arrested. With a special court convened at Lisburn Courthouse on 8 August the women used the classic W.S.P.U. tactics to undermine the proceedings. Between them they attempted to filibuster, spoke over the prosecutor and charged the dock. It was a farce. Metge repeatedly called for the entire case to be dismissed, on one occasion attempting to leave the courtroom, before having to be restrained:

'Gentlemen, I know what it is. There is one law for women and another for men. A woman could not get justice here. I'm going home.'

She did not, for the evidence against them was compelling and clear. Footprints in mud and dew led from the Cathedral to Metge's house. When the house was raided, the four suffragettes were fast asleep, with wet overcoats and muddy boots hanging out to dry. Fuse matches were in their pockets and a fine silk handkerchief was at the scene. Hugh Kirkwood, keeper of Kirwood's Hardwares recounted at the trial that Metge had visited some months before, claiming to want to buy a new stove. She was dismissed from his store having wanted to 'buy some dynamite to blow up a tree in the garden.'

It would appear that whilst under arrest during the trial, Metge went on her Hunger Strike, with the Medal bearing the date '10 August 1914'. With war being declared on 4 August, the trial continued until 12 August, when the Home Secretary called a truce and remitted all suffragette sentences and the unconditional release off all those on trial. Emmeline Pankhurst called for the cessation of all militant activity by the W.S.P.U. on 14 August 1914.

Metge remained a member of the W.S.P.U. and continued to write for The Irish Citizen. She settled in south Dublin, died in 1954 and is buried in Deansgrange Cemetery.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£8,500