Auction: 18001 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 44

'The last time I saw Jack Parsonson - Major J. E. Parsonson, D.S.O. - in the Western Desert was on 16 August 1942, when he and his close friend, 'Rosy' - Colonel S. F. du Toit, C.B.E., D.F.C. & Bar - flew in my section of 2 Squadron's Kittyhawks on a reconnaissance of the Alamein Line. I got rather badly hurt on that sortie and had to swim some of the way home. As a result, I was not able to witness more of Jack's memorable tour of operations, but I have since heard him tell of these exciting times.

When Jack and Rosy were posted to 2 Squadron of the South African Air Force as supernumerary Captains in July 1942, they had both seen action against the Italians in East Africa. Each went on to command a fighter squadron during those hectic months of combat from Alamein to Tunis, Rosy leading 4 Squadron right to the end of the North African campaign with Jack in charge of 5 Squadron until he was shot down just before the finish.

Jack Parsonson was, in fact, shot down three times - first, by Afrika Corps light flak, then by the Luftwaffe - a gaggle of Me. 109s - and, finally, by the German Kriegsmarine (a motor torpedo boat). It was an extraordinary story of escape, recapture and then escape. It was on the third occasion, on 30 April 1943, that his luck ran out.

Gunfire from the E-Boat he was attacking hit his aircraft in the coolant rad. As he was going down, streaming glycol, his calm voice, sounding very matter of fact, came over the R./T. "Well boys, I've had it!" He ditched in the sea near Zembra Island, paddled ashore in his dinghy, and hid up for two nights and a day.

Confident that if he could reach the mainland in darkness he could then evade the enemy, he set out to paddle the dozen or so miles to the shore. Unfortunately, he was spotted, taken prisoner and this time they made sure he didn't get away. So, while Rosy du Toit survived four operational tours and was, in time, promoted to command 8 Fighter Wing of the S.A.A.F. as a full Colonel, poor old Jack champed at the bit in Stalag Luft III.

Jack Parsonson's reluctance ever to shoot the line often leaves one wondering just how he really felt when the chips were down. When you ask him about it, he just laughs and passes it off. "I was terrified, old boy, absolutely petrified. But weren't we all?" And still one if left wondering … '

A tribute by Major-General R. 'Dick' Clifton, S.A.A.F., refers; see Thanks for the Memories, by 'Laddie' Lucas.

The rare Second World War Desert Air Force ace's D.S.O. group of five awarded to Major J. E. 'Jack' Parsonson, South African Air Force (S.A.A.F.), whose truly remarkable wartime career is described in his colourful memoir A Time to Remember

Whether he took up his entitlement to membership of the Late Arrivals and Goldfish Clubs remains unknown, but he was thrice shot down and twice evaded capture: no wonder his favoured exclamation was "Isn't it marvellous to be alive!"

Packed off to Stulag Luft III after being downed for a third time - whilst leading No. 5 (S.A.A.F.) Squadron in a low-level attack against E-Boats - he assisted in the famous 'Great Escape' but was not among the 76 officers who exited 'Harry', the alarm having been sounded: instead he faced two German officers brandishing pistols at his chest …

Distinguished Service Order, G.VI.R., silver-gilt and enamel, the reverse of the suspension bar officially dated '1943'; 1939-45 Star; Africa Star, clasp, North Africa 1942-43; War Medal 1939-45, M.I.D. oak leaf; Africa Service Medal 1939-45, these four officially inscribed, 'P102686 J. E. Parsonson', together with his embroidered S.A.A.F. Wings and three metalled S.A.A.F. badges, occasional edge bruise, generally good very fine (9)

D.S.O. London Gazette 25 May 1943. The original recommendation states:

'This officer is a fearless, determined and skilful fighter, whose example has proved most inspiring. On two occasions his aircraft has been shot down but, displaying great fortitude, Major Parsonson succeeded in re-joining his squadron. In recent air operations in the Tunisian theatre, this officer flew with distinction. In April, he participated in an engagement during which a convoy of transport aircraft was destroyed off the Tunisian coast. A few days later, he led a formation in an attack on a large number of similar aircraft over the Gulf of Tunis. During the action 20 of them were shot down, two being destroyed by Major Parsonson. His fine fighting qualities are worthy of high praise.'

John Edward 'Jack' Parsonson was born at Smithfield, Orange Free State, South Africa on 20 November 1914 and attended Queen's College, Queenstown. Having then joined the Active Citizen Force, he received a permanent commission in the South African Field Artillery in February 1938. Major-General 'Dick' Clifton takes up the story:

'Jack, like Rosy and me, was a product of the pre-war South African Military College. In those days, cadets were trained in infantry and artillery duties while, at the same time, being taught to fly. Once commissioned, he chose the Field Artillery because it promised the most exciting life. In a Horse Battery of 4.5-inch howitzers, there was ample opportunity for equestrian pursuits, and Jack loved horses almost as much as he loved aeroplanes.

He was handsome and he sat a horse superbly. On his coal black charger, 2nd Lieutenant Parsonson looked magnificent with his immaculate riding breeches and Barathea tunic, highly polished riding boots and Sam Browne belt.

His other great advantage in joining the Artillery was that once a week he could fly any of the Hawker Harts or the beautiful Hawker Fury, whereas fellow cadets who had chosen the Air Force found themselves on an instructor's course flying Avro Tutor trainers. However, when war broke out Jack lost no time in transferring to the S.A.A.F.'

No. 3 (S.A.A.F.) Squadron - East Africa 1941-42 - first blood

Posted to No. 3 (S.A.A.F.) Squadron, which was equipped with Curtiss P-36 Mohawks and based on the border of Ethiopia and French Somaliland, Parsonson was credited with the destruction of a Savoia Marchetti 75 on the ground at the Vichy French airfield at Aiscia, Jibouti on 5 October 1941.

No. 2 (S.A.A.F.) Squadron - North Africa 1942 - mounting score

Towards the end of the summer of 1942, Parsosnon transferred to No. 2 (S.A.A.F.) Squadron in the Western Desert, flying Kittyhawks, and his guns were soon back in action.

He damaged a Mc. 202 over Alam el Haifa on 29 August; damaged a brace of Me. 109s over Duba on 9 October and destroyed a 109 over the Alamein area on 26 October.

Downed - evasion - Late Arrivals Club

On 1 November 1942, whilst strafing enemy troops and transport, his Kittyhawk was hit by ground fire and he was compelled to make a forced-landing in the Qattara Depression.

An epic 21-mile desert walk ensued before he reached Allied lines two days later, a journey encompassing some hair-raising moments, not least the occasion he unwittingly walked into an enemy minefield. He also suffered from mirages and a number of falls but was eventually picked up by a patrolling jeep of 40 Recce Squadron, S.A.A.F.

Downed - escape

On 10 November 1942, over Tobruk, he faced even greater odds, being attacked head on by four 109s. A desperate combat ensued, the fight beginning at 17,000 feet and quickly spiralling downwards. At 8,000 feet four more 109s joined the fray and his Kittyhawk shuddered under a torrent of cannon fire. Gaping holes appeared in the mainframe and, as he neared deck level, another cannon shell just missed his right shoulder and slammed into the instrument panel, shattering the oil tank. Cannon fire continued to hit his Kittyhawk even as it a touched the ground at a speed of 180 m.p.h., 'skimming over the surface like a flat stone thrown across water.'

When the shattered aircraft finally came to a halt, Parsonson threw off his harness and parachute straps and exited the cockpit under fire, making for the cover of a roofless stone hut:

'The German pilots seemed determined to kill him. They were not satisfied with merely shooting him down. After a while the attack ceased and he looked cautiously out of the hut to see what was happening. All eight 109s were still circling like hawks waiting to pounce on their prey!

He crouched down in the hut and after a short while heard the sound of an approaching vehicle. Drawing his revolver he peered over the top of the hut's walls and saw a two-ton truck laden with armed soldiers. It stopped a few yards away and realising the futility of his revolver he stuck it back in his holster, walked into the open and raised his hands in surrender. A very decent young German officer walked up and after looking him up and down for a few moments said: "You must be feeling very tired. The war is over for you. Would you like this egg? Make a hole in each end and suck it. You'll find it very refreshing." He then offered him a cigarette and told him to climb aboard the truck' (Passion for Flight, by Peter Bagshawe, refers).

Following a night in captivity near Fort Capuzzo, Parsonson's journey was hastened by the arrival of British tanks. Taking advantage of the diversion, he leapt from his truck and ran for a gully, the ground around him being kicked up by automatic fire. A game of cat and mouse ensued but at length he was surrounded and recaptured: his guards beat him up with rifle butts and he was warned that if he made another attempt to escape, he would be shot out of hand. His journey then continued, a journey in which he saw Rommel pass on four separate occasions in an open Volkswagen; he was also introduced to a pair of black South African prisoners, 'sterling men who had been captured at Tobruk.'

At length, Parsonson braced himself for another escape attempt. He takes up the story in A Time to Remember:

' … We sat in the well of a truck with our backs to the engine just behind the cab. The Sergeant sat on my right and the Sergeant-Major on my left. The rest of the crew - five or six of them - rested further back. The night was very dark and we were nose-to-tail in the long column.

The Sergeant-Major drew his Luger and told me that if I tried to escape he would be happy to shoot me. Twice during the long, boring drive I felt him raise the blanket covering the three of us to peer surreptitiously underneath. I pretended to be dozing.

Just before first light I had a curious feeling, I sensed everyone was fast asleep and that I must get up very slowly, which I did. All that was necessary was to stretch quietly over the Sergeant-Major, put my hand on the side of the truck and vault over it to the ground. The column was moving very slowly so it would be no great feat. … '

Nobody stirred as he walked quietly down the line of lorries in the opposite direction to which they travelled but, after about 100 yards, 'a frightful din' broke out: his escape had been discovered and he ran for it. Luckily good fortune prevailed and, rather than a Luger bullet, he encountered a friendly Bedouin shepherd. That good fortune was very much apparent when the Bedouin showed Parsonson a letter from Lieutenant-Colonel Carlyle of the Long Range Desert Group, a letter stating the bearer to be a trustworthy man who would assist Allied troops. And so it proved, Parsonson reaching our lines on the following day.

He was sent to H.Q. 4th Armoured Division and, on re-joining his squadron, was quickly back in action. His final notable combat in 2 Squadron was fought on 1 December 1942, when he took a half-share in a Mc. 202.

Command of No. 5 (S.A.A.F.) Squadron - ace status - downed

Early in 1943, Parsonson was appointed to the command of No. 5 (S.A.A.F.) Squadron, and operations continued apace. In his won words, 'We were doing two or three shows a day and I suppose the tension was increasing. Apart from the intensive operations our Kittyhawk 1s were badly worn out and many lame ducks limped home and some could not get home.'

That tension - and the burdens of command - finally came to head in mid-April when Parsonson was invited by his Adjutant and Intelligence Officer to heed some words of advice: to ease their task, he tore off his crowns of rank, thereby allowing them to speak frankly:

'They shuffled a bit more and then said, "You've got a sort of mutiny on your hands. The pilots are very unhappy about you; you go about with a grim look on your face and don't smile anymore … That evening I made a point of grinning and being cheerful again. I know that underneath I was worried about being hacked for the third time, and this showed that worry can be contagious … ' (ibid).

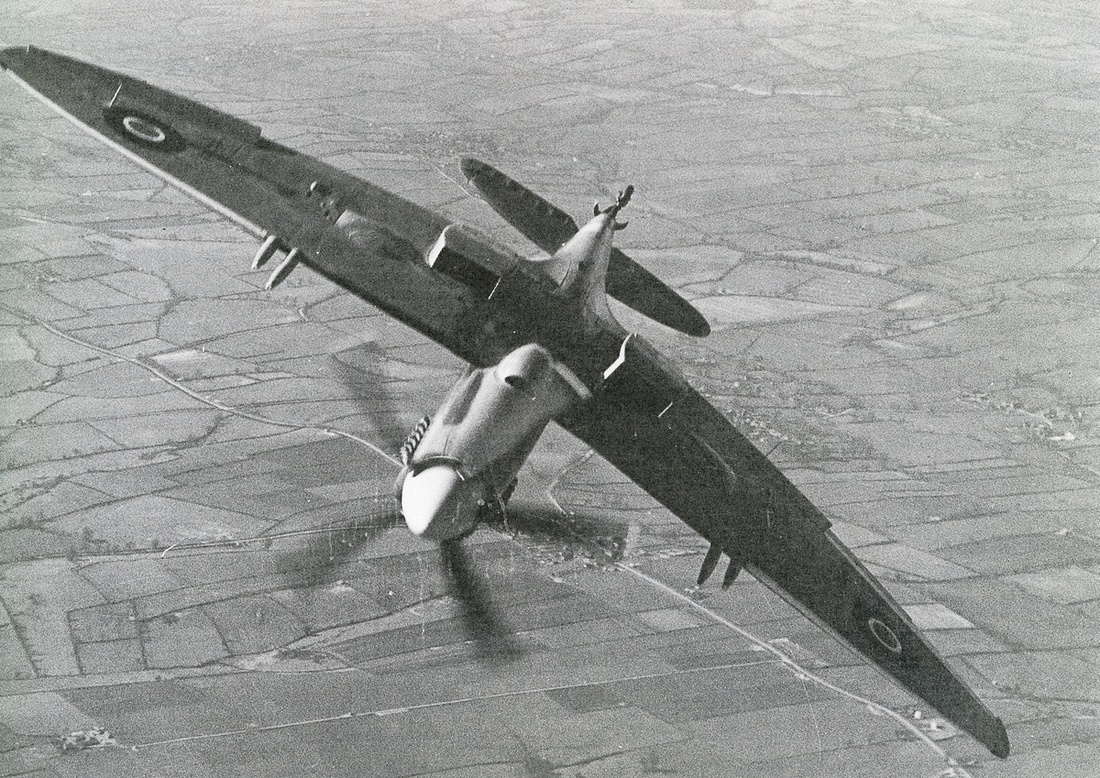

Meanwhile, however, happier times did indeed prevail. Whilst returning from a patrol on 19 April 1943, 5 Squadron sighted a mixed formation of Ju. 52s and S. 79s, with fighter escort. With 4 Squadron dealing with the escort, Parsonson and his fellow pilots dived into the formation of transports and 'shot them to pieces, Junkers and Savoias bursting into flames, crashing and exploding everywhere'. The Squadron's bag amounted to seven destroyed.

'The Massacre of Cap Bon'

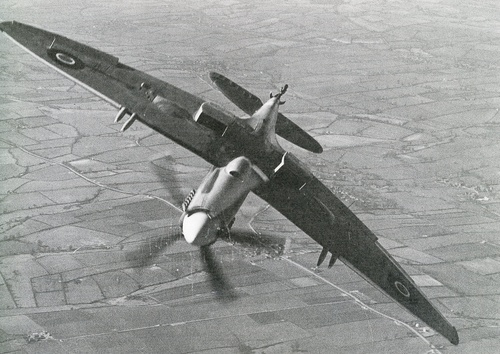

On 22 April 1943, Parsonson and his pilots enjoyed even greater success, when they encountered a formation of Me. 323s off Cap Bon. He takes up the story:

'As we passed over the coast north of Korbous I saw something which I could hardly credit. Out of the morning mists, coming towards Tunis, appeared a balbo of Me. 323s, six-engined transport aircraft in two huge Vs escorted by numerous fighters. These gigantic aeroplanes, capable of carrying unprecedented loads, were below and to our right. I turned the wing down towards them, gave the order to attack and then it was up to each pilot to select his own target. My squadron had the advantage of going first. 4 Squadron followed us while 1 and 2 Squadrons piled into the enemy fighters. Then, on a much larger scale was a repetition of the previous show. The Me. 323s were so large they could not be missed and our heavy .5s wreaked havoc among them. The carnage was horrific as these transports were mainly carrying fuel for the beleaguered Afrika Corps and the remnants of the Luftwaffe. As they were hit a large number burst into flames. When they hit the water the petrol spread and it seemed that the sea itself was alight. All but one of the 323s were despatched … No. 5 Squadron destroyed 15 transports, 4 Squadron destroyed nine, 2 Squadron shot down one Re. 2001 and 1 Squadron destroyed five aircraft.'

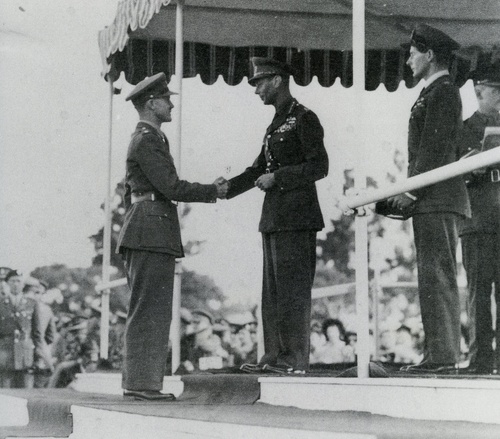

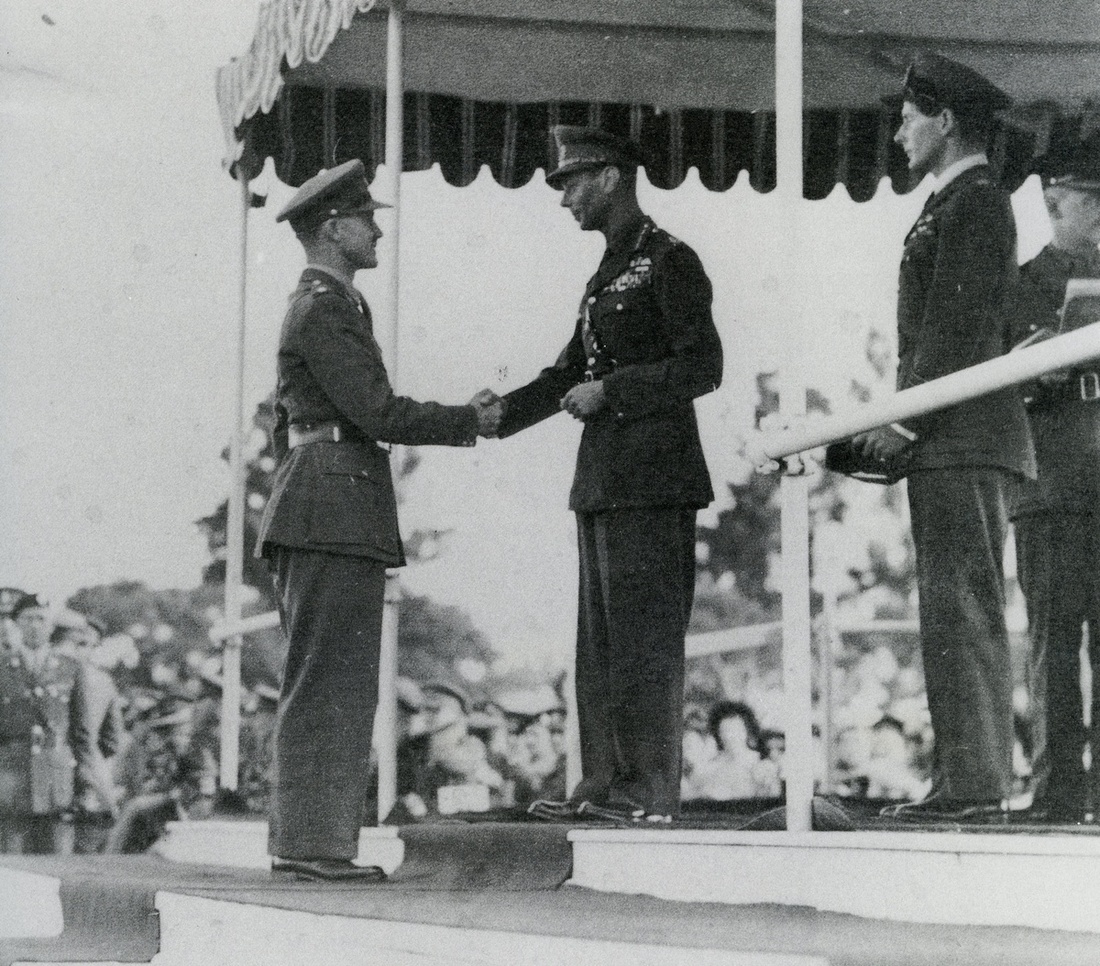

Parsonson - who accounted for two of the giant transports - was awarded an immediate D.S.O.

'Hacked' for a third time

On 30 April 1943, whilst attacking enemy E-Boats, his aircraft was hit by flak and he had to ditch in the sea off Zembra Island:

'Between Tunis and Zembra Island we saw three E-Boats below. There were no other targets so I ordered the two bombed-up squadrons to form echelon right and down we went. All the bombs missed so we continued down to water level to attack with our .5 Brownings. As low as possible I approached from the beam. The shooting was easy for us, but so it was for the defending gunners. The E-Boat was in flames as I passed over and I knew the chaps behind would certainly sink it. I also knew I had been hit in the glycol so told Rod to take the Wing home.

I flew towards Zembra Island knowing very well that I did not have much time before the engine seized. I turned past the island so that I could attempt a landing on the water on the far side of the E-Boats. I circled low and landed with nose well up about a hundred yards from the shore. The big air scoop under the nose of a Kittyhawk made landing on water a very problematical undertaking. I landed lightly, tail well down and the aircraft settled nicely on the water, and only then realised that the canopy was still closed and the radio leads not disconnected. Hastily I opened up the canopy, which fortunately did not jam, pulled off my flying helmet with leads, undid the straps and got out on to the wing root. I ripped off the dinghy and slid into the water and the aircraft sank moments later. I blew up the dinghy, clambered on and saw the cliffs quite close. It did not take long to paddle with my hands to land.

The coast is very rocky just there, but it was easy to climb ashore. Taking the dinghy with me and hiding it carefully, I climbed the steep face of the cliff. I reached a place where there was good concealment and made myself fairly comfortable waiting to see what would happen. I was well hidden when an E-Boat came round the headland. It circled slowly while one of the men on board searched the sea and island through binoculars. There was nothing for them to see. My beautiful new engine Kitty - GLX - was at the bottom of the sea and I was well concealed on the hillside. After a while they returned the way they had come' (ibid).

Having found another vantage point, Parsonson witnessed his Wing's return to finish off the damaged E-Boat. He then settled down for the night, after a moment of quiet reflection:

'It was interesting to consider that I had been shot down three times, the first time by the Afrika Corps at El Alamein, the second near Cappucco by the Luftwaffe, and now the third time by the Kreigsmarine. Ground, air and sea, was it unique?' (ibid).

Unbeknown to Parsonson, his squadron had organised for a naval gunboat to roar over to Zembra Island to affect his rescue: but he was fast asleep as the gunboat circumnavigated the island with its gallant skipper hailing him by name.

Early on the following morning, Parsonson took to his dinghy, hoping to paddle by hand to the mainland some 12 miles distant. As he closed the shore he came under fire from Italian troops. The game was up and he was carted off to Tunis and thence, in the back of a Ju. 52, to Sicily and Rome. Ideas of escape were never far from his mind but on all occasions his armed escort was very on the ball, not least the two soldiers who guarded him during his subsequent journey by rail to Germany. His destination was Stalag Luft III at Sagan.

The Great Escape

Parsonson soon settled down to life as a P.O.W.; one of his first letters from the outside world was the notification of his award of an immediate D.S.O., with a length of riband enclosed.

He also came to know the camp's more prominent inmates, among them a fellow South African, Roger Bushell, the camp's escape officer, or 'Big X' as he was known to his fellow inmates. For escape was very much on the agenda and the Germans knew it:

'One day there was a great disturbance, masses of German soldiers, armed to the teeth and wearing steel helmets poured into the camp. There was a curious feeling of sinister force and dangerous influences. We were all routed out and formed up on the parade ground where we had our daily roll-call, and we waited for hours. Eventually a German General and his entourage bustled in accompanied by several civilians dressed in sombre clothes. We heard that these were members of the Gestapo. The fat little General harangued us for hours, through an interpreter, while the Gestapo and ferrets poked about through the blocks. They took up the whole day but didn't find anything of consequence' (ibid).

Meanwhile, Roger Bushell and the camp's escape committee were flat out on three tunnel schemes - 'Tom', 'Dick' and 'Harry'. In the event, 'Tom' was discovered by the Germans and, with soil disposal an ongoing issue, it was decided to push on with 'Harry'. Parsonson was clearly involved in this operation, one source even crediting him with tunnel digging. As a consequence, he was among those given a place in the actual escape on the night of 23-24 March 1944, together with his friend 'Jimmy' Chapel - 'Finally, after a further draw the escape committee decided to tack our two names on the end of the list [of escapers] as we had worked very hard and were very keen' (ibid).

The events of that memorable night have been the subject of considerable coverage. Suffice it to say that Parsonson was still gathered with fellow 'escapers-to-be' in Hut 104 when the alarm was sounded. The whole quickly disposed of their maps and compasses in the hut stove and awaited the arrival of the German panic parties:

'Finally, the doors were unbarred and a call for the Senior British Officer to come out was shouted. I glanced around and saw Squadron Leader Griffiths, a New Zealander in the R.A.F. and said to him, "You're the senior officer. You go out!" He replied, "No, you are!" We each lit a cigarette, assuming a nonchalance that neither of us felt, and walked out together.

Outside a mass of armed soldiers stood in a circle around the end of the block with their rifles and sub-machine guns at the ready and wearing steel helmets and greatcoats. The looked formidable. Oberst von Lindeiner, the camp commandant, stood in the middle of the circle flanked by the senior members of his staff. The Oberst was obviously in a towering rage. He rapped out an order. "Geschutz!" On the order, 'Rubberneck', the senior ferret, and Glimitz pulled out their Lugers and pointed them at my chest. I thought that Geschutz meant shoot. I thought my last moment had come and could practically feel the heavy bullets striking me in the chest. Nothing happened for a moment and I thought, "I'm still alive." With that all the kriegies were called out and we were lined up in front of the barrack block. As soon as we were all outside we were marched to near the front gate and told to strip naked. It was a cold day with a bit of snow around. We stood there all day while the Germans searched 104 and did a count of all the prisoners in the compound … ' (ibid).

Parsonson's memoir goes on to describe the terrible news of the murder of 50 of his fellow officers, among them two South African pilots known to him, Lieutenants Gous and Stevens: 'The feeling in the camp remained suicidal for some time and some ideas of retaliation were talked about before things returned to normal.'

With the subsequent advance of the Allies in March 1945, Parsonson and his fellow kriegies were force-marched west in atrocious weather. Towards the end of April, his party stopped at a farm 12 miles short of Lubeck, where the German guards began to lose interest in their charges. A few days later there was the sound of vehicles and shouting:

'We rushed back to the road and saw the most wonderful sight … Montgomery's men had arrived and we were free! A story which we appreciated was told of the first jeep to arrive. A British Lieutenant-Colonel sat beside the driver as they drove slowly in. One of the German guards was standing sloppily with a cigarette in his mouth. The jeep stopped and the Colonel got out, went up to the German and struck him in the mouth with his fist, "How dare you stand there and smoke in front of a British officer!", he roared at the man' (ibid).

Parsonson was flown to the U.K. and thence to Italy, where he met up with his old South African comrades in 8 Wing. In due course he was appointed to the acting rank of Lieutenant-Colonel and given command of the Wing, in which capacity he logged many enjoyable hours flying Spitfires over the Italian countryside. Then in November 1945, he was ordered home.

The latter years

Having retired from the S.A.A.F. in 1954, Parsonson became a tobacco farmer in Rhodesia. His old friend, Major-General 'Dick' Clayton, later wrote:

'However, it wasn't even Jack Parsonson's success as a leader that made him such a remarkable character. He had so many qualities, but there was one which, I have always thought, set him apart. This was his extraordinary generosity. As long as I have known him, in war and in peace, it has always been fatal to admire any of his possessions because he would promptly insist on giving it to you.

There was a remarkable example of this attribute years after the war when he was growing tobacco very successfully in Rhodesia. He had long since retired from the S.A.A.F. and had married for a second time. His new wife's first husband, Guy Oliver, had suffered a stroke as a result of a war wound. This left him badly paralysed and quite helpless.

Jack then built a cottage on his farm specially for him to live in and where he could be properly looked after. There, Guy lived happily until he died. It was a notable act of humanity and quite exceptional, and that is why, with all that has gone, I have selected Jack Parsonson as the most memorable character I came to know in the war' (Thanks for the Memories, by 'Laddie' Lucas, refers).

Parsonson returned to South Africa in 1981 and died at Hermanus on 16 August 1992; sold with an extensive file of copied research, in addition to a copy of his memoir A Time to Remember.

Note:

Parsonson's original Flying Log Book is held in the collection of the S.A.A.F. Museum at Swartkops; it is available for viewing on:

http://saafww2pilots2.yolasite.com/jack-parsonson-log-book.php

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£4,500