Auction: 17003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 599

'It is reasonable to assume that the eight remaining Blenheims, flying at 50 feet along that front of 3 or 4 miles, would have been facing at least twenty batteries of 37mm. and ten of 20mm. guns, with a combined firepower of 62,400 rounds per minute - an average of 7,800 rounds per minute against each aircraft. And this does not include machine-gun fire, either from the flak batteries or from troops in the streets or guarding factories or barracks. No wonder then that Hughie Edwards could write of it later, 'The flak was terrible - I saw nothing like it in my wartime operations before or after'.'

Shocking facts well-known to Sergeant W. B. Healy, an Observer who flew in a Blenheim of No. 105 Squadron in the spectacular low-level daylight strike on the docks at Bremen on 4 July 1941; Battle-Axe Blenheims, No. 105 Squadron at War 1940-41, by Stuart R. Scott, refers.

An outstanding Second World War 'V.C. action' campaign group of four awarded to Sergeant W. B. Healy, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, whose Blenheim flew on the port wing of V.C.-winning Wing Commander "Hughie" Edwards's aircraft in the spectacular low-level daylight strike against Bremen on 4 July 1941

Participation in the epic Bremen raid aside - during which a large shell ripped into his aircraft's fuselage and exploded in the air gunner's well - Healy's tour of duty in the Blenheims of 105 Squadron was likewise marked by much flak damage incurred at deck level

On 26 August 1941 - and having been informed of his pending return from Malta to the U.K. for a rest - he and his crew were ordered at short notice to carry out a shipping strike off Tunisia: in running in over the wavetops to deliver their attack, their Blenheim failed to gain sufficient height to clear the enemy merchantman's masts

1939-45 Star; Air Crew Europe Star; Africa Star; War Medal 1939-45, extremely fine (4)

Walter Brendan Healy commenced training as a Navigator and Air Observer in June 1940 and, having qualified at the year's end - and attended an O.T.U. - he joined No. 105 Squadron, a Blenheim unit operating out of Swanton Morley, in April 1941.

'Churchill's Light Cavalry': low-level operations of the hair-raising kind

His first operation, a shipping strike flown on the 17th, proved a memorable one. Battle-Axe Blenheims, No. 105 Squadron at War 1940-41, by Stuart R. Scott, takes up the story:

'The danger of unescorted low-level operations was now to become all too evident, and the other two aircraft were not so fortunate. On the return journey, two Bf 109 yellow-nosed fighters pounced on the Blenheims … The other Blenheim, crewed by Sgt. 'Arty' J. Piers, a Canadian pilot, Sgt. W. Brendan Healy (Observer) and Sgt. Stuart George Bastin (W.Op./A.G.), also came under attack, in an engagement which lasted for twenty minutes. Watching with horror as Sgt. Serjeant's Blenheim fell to the fighters, and with both guns and radio out of action, all the gunner could do was sit and pray. The yellow noses of the Messerschmitts appeared time and time again. Following instructions shouted back from the gunner, the pilot took evasive action, as they slipped and skidded over the sea, churning only feet below them. Eventually, having outwitted the 109s, and with considerable damage to the aircraft, they returned to St. Eval, where T-1885: F crash-landed safely. For the nineteen-year-old gunner and the rest of the crew, their inaugural operational flight with 105 Squadron had been a memorable one - with a repeat performance yet to come only eight days later on the 25th!'

On 25 April, Healy's crew was one of four selected to attack the Royal Dutch Blast Furnace and steel works at Velsen, a suburb of Ijmuiden. The formation, led by Squadron Leader David Bennett, took off from Swanton Morley at 09.25 hours. Healy's gunner, Sergeant Stuart Bastin, takes up the story:

'Lovely clear morning bright blue sky. Flying a few feet above the sea, we soon saw the Dutch coast about 15 miles away and we were shortly able to pick up out target. Travelling at over 350 ft. a second, our pilot climbed a little to clear some sandhills. It's a wizard thrill to rush in on the target at this great speed. As we cleared the sandhills the flak started - tracers, and brown and white puffs all over the place - bangs and pops just like a fireworks display. I saw Jerries running all over the place in a terrific panic and one of my pals said afterwards he had seen a fat German doing the ostrich trick behind an exceedingly small bush. Suddenly the kite gave a lurch and several large holes appeared in the wings. I swung the guns over to the offending gun crew, fired a long burst, and had the satisfaction of seeing the crew fall around their gun - another gun less to deal with. By this time, the plane was wobbling towards the ground with the tall factory chimneys well above us. I yelled to the pilot that there were three big holes in the wings, and he yelled back, "Oh, anyway the starboard engine is stopping." The Observer [Healy] chimed in with "we are covered in oil." I then noticed smoke pouring out of the starboard engine. The pilot managed to get the kite on an even keel again, just in time to miss an overhead pipeline. How the pilot managed to keep her in the air is rather beyond me. I heard the Observer shout, "Left, left, bombs gone." The pilot now turned towards the sea and home. I saw bombs burst across some thickly packed loaded barges and dockside buildings in the target area. The Jerries were still running all over the place, some towards their guns, mostly towards shelters. One crew never reached the guns. The engine began to pick up again, much to my relief, but there was still smoke and the threat of fire. We got away without further damage. The Germans were putting up a very heavy barrage over the target, fortunately a little too late. Another plane, seeing our predicament, turned and kept guard on us all the way home. I was a bit worried as I could see white trails left behind by fighters, right above us. No machine was more welcome than our guardian. We managed, due to the pilot's skilful handling, to reach our base on E.T.A.' (ibid).

It was another crash-landing, their shot-up Blenheim skidding to a halt on the grass at Swanton Morley.

Having in the interim also flown a "Circus" to Le Havre and an anti-shipping strike to Rotterdam, Healy - and Bastin - were joined by a new pilot, Sergeant R. J. 'Ron' Scott. They were quickly back in action, attacking enemy shipping off Norway, including a merchantman in a fjord off Bergen on 16 May, which was claimed as a total loss. About ten days later, in a similar sweep off the Frisian Islands on the 25th, 105's Blenheims ran into an enemy convoy defended by three flak ships. Healy's crew claimed another enemy merchantman as a total loss.

In June, Healy flew further anti-shipping operations off the French and Dutch coasts, in addition to taking part in two abortive attempts to attack the docks at Bremen. The latter shortcoming was about to be corrected in spectacular fashion.

V.C. action

Thus to the famous low-level daylight strike on Bremen on 4 July 1941, an epic in the annals of Royal Air Force that culminated in the award of the Victoria Cross to its leader, Wing Commander H. I. "Hughie" Edwards of 105 Squadron. As cited above, the unprecedented scale of the opposition they encountered led him to conclude: 'The flak was terrible - I saw nothing like it in my wartime operations before or after.'

The attacking force comprised nine Blenheims from 105 and six from 107 Squadrons. Three of the latter were forced to abandon the operation but the remaining aircraft proceeded to the target in tight formation - among them Healy's Blenheim, which flew on Edwards's port wing. In the approach to the target, Edwards's remaining formation took heavy punishment from the curtains of accurate flak and four of his aircraft were swiftly shot downed in flames. The remining eight, Healy's still among them, close on his leader's port wing, pressed on undaunted:

'Sergeant Scott in Z7361:R [Healy's aircraft] dropped his bombs on the Dyckhoff & Widmann Factory area; one hit the factory, the remainder severely damaged the storage depot, an army vehicle depot and a stretch of railway lines, in addition to three goods warehouses. During the attack, the aircraft suffered damage to its pneumatic systems. A large shell ripped into the fuselage, exploding in the air gunner's well and severely bruising Sgt. Bastin's back, as the shrapnel cut through his parachute harness. The main electrical panel was missed by inches.'

Of the seven aircraft that finally made it back to Swanton Morley, all were in one way or another severely damaged, one of them trailing a length of severed telegraph cable. Owing to his pneumatic brakes being unserviceable, Healy's pilot had trouble in bringing their shot-up Blenheim to a halt. Their much-bruised gunner - Stuart Bastin refused to report to the M.O. for fear of being taken off operations. "Hughie" Edwards's gunner, Sergeant Gerry Quinn, D.F.M., was more seriously wounded and had to be extricated from his shattered gun turret by crane before being loaded into an ambulance.

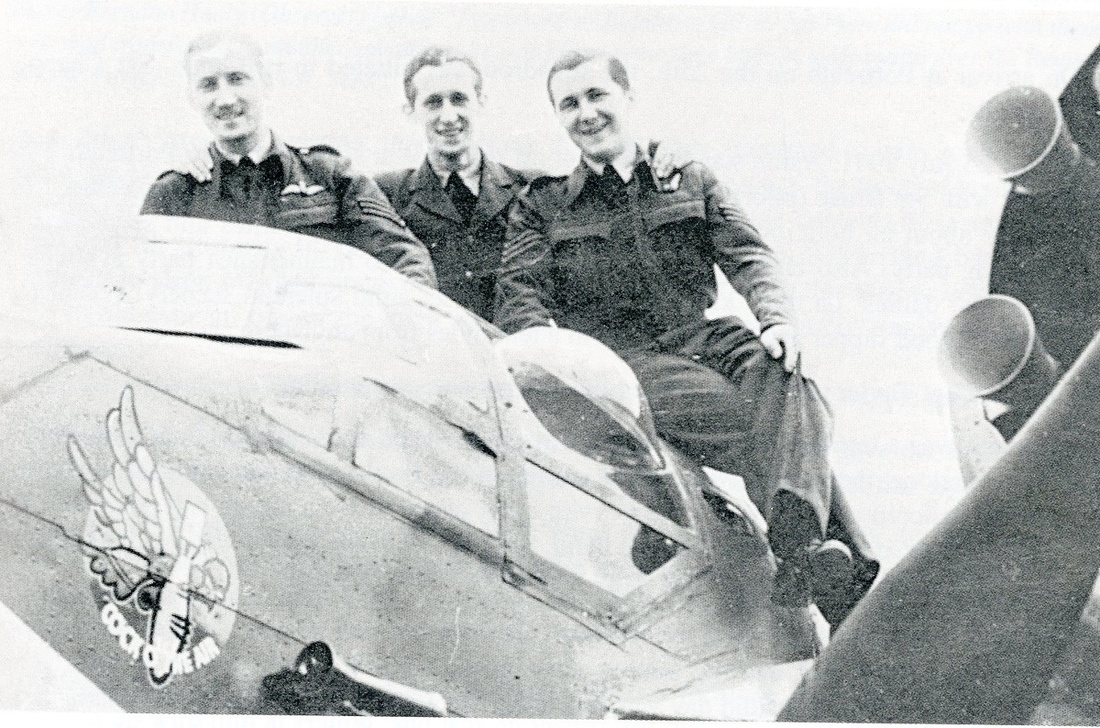

News of the raid's success spread fast, with tributes flowing in from all quarters. On 21 July it was announced that "Hughie" Edwards was to be awarded the V.C. It was a popular award, the bruised Stuart Bastin writing to his sister, 'We are all hugging ourselves about it, '105' is on top now. We got no medals but it feels great to think we were on the same job, we were flying on his left the whole time.'

Malta - journey's end

In late July, 105 Squadron was ordered to Malta, from whence Healy flew his first sortie on 3 August, an attack on shipping at Tripoli: his Blenheim was hit by flak in the fuselage and flaps. A day or two later, he and his crew were back in action in an attack on Misurata on the Libyan coast, gaining a direct hit on an ammunition dump, in addition to shooting up petrol tankers and an A.A. gun. And 105's relentless agenda of operations continued apace for the remainder of the month, and included the loss of yet another Squadron C.O.:

'By now, one of the longest serving 105 Squadron crews was due for relief. Sgt. Ronald Scott, aged 26, an experienced and highly respected pre-war pilot, was to return to be commissioned. His Observer, Sgt. Walter Brendan Healy was also to return, along with Sgt. Stuart George Bastin, W. Op./A.G., the youngest squadron member at only 19 years of age. Together they had operated as a very close-knit crew since May 1941. All were now to return 'on rest' to transfer to O.T.Us and probably split up and go their separate ways. A Sunderland boat was to take them on the first leg of their journey home in a few days time' (ibid).

It wasn't to be:

'While the Sergeants were standing around chatting at Marsaxlokk [on 26 August], with the waves lapping their way carelessly up the slipway, the tranquillity of the scene was interrupted by a message from the mess. The day was not to be a quiet one after all; the crews were summoned to Luqa on standby, Sgt. Scott's included. He and his crew were reluctant to go on another operation so near to their return and had a strange feeling of foreboding about the trip, which, atypically, they voiced to their comrades. Sgt. Bastin had typified the feeling in an uncharacteristic exclamation of "Oh, God!" when he heard the news … However, off they went, as the bus rolled its way along Marsaxlokk Bay, past the Honeymoon Hotel to the church, where a left turn took them up the hill and around the invasion obstacles as they set course for Luqa' (ibid).

As fate would have it, one of the crews eventually chosen had to drop out at the last minute on account of the pilot going down with sandfly fever: Healy and his comrades were ordered to take their place.

They took off from Luqa at 11.30 hours, accompanied by another Blenheim of 105 piloted by Sergeant 'Bill' Brandwood. The first of their targets - an enemy ship off Tunisia - hove into view at about 12.40 hours. It was quickly apparent the ship had already received sufficient damage from an encounter with the Royal Navy, so the two Blenheims proceeded to a point east of the Kerkenna Islands, where another enemy ship had been reported:

'It was at 13.00 hours, with a bright sun high in the sky, as the leader, Sgt. Scott, dropped right down on the deck, just skimming the wavetops for a run at the ship. This ship had not suffered the fate of the first and was well afloat with small boats proceeding away from it to the north-west, heading for the coast. One of the dhows was tied up alongside the ship as Sgt. Scott approached for a quarter attack. The wingman [Sgt. Brandwood] held off in a parallel course as this time the run-in was a bombing run, and in this way the aircraft would avoid running into the leader's 11-second delayed bomb fuses. No sign of anti-aircraft fire was evident and no tell-tale blips on the water's surface from small-arms fire could be seen. Closer and closer the Blenheim roared in towards the target. The ship's superstructure grew in relation to the aircraft as it closed in, the masts looming upwards like great endless pillars into the blue sky above. The Blenheim would have been well trimmed out as it pulled up on discharging its bombs into the side quarters of the ship; however, having gained some height, the aircraft mysteriously levelled out and Z7682:N ran headlong into the mast, damaging the superstructure as it exploded, before the remains were hurled into the water beyond. For Sgt. Scott, Sgt. Healy and Sgt. Bastin, the pains of war were over in an instant.'

The son of John and Elizabeth Healy of Droylsden, Manchester, Healy has no known grave and is commemorated on the Malta Memorial. He was 23.

Sold with the recipient's original R.A.F. Observer's and Air Gunner's Flying Log Book, covering the period June 1940 to June 1941, with closing endorsement 'Death Presumed 26.8.41'; the lacking entries between June and his death in action in August are surely attributable to 105 Squadron's move to Malta; owing to that move, the recipient flew no further sorties in July, other than the strike on Bremen on the 4th.

Additional reference sources:

Scott, Stuart R., Battle-Axe Blenheims, No. 105 Squadron at War 1940-41 (Alan Sutton, Stroud, Gloucestershire, 1996); including quote taken from Blenheim on the Deck, by Michael Scott.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£650