Auction: 17003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 576

'Duncan, Christina, Stewardess, 19, Fernhill Road, Bootle. Gold ring, single diamond, gold wristlet watch & bracelet, fair hair, good looking, 33 years, name on belt.'

A missing persons' description received by Cunard after the sinking of the Lusitania in May 1915, refers.

The poignant Great War campaign pair awarded to Christina Duncan, Mercantile Marine, one of 14 stewardesses lost on the occasion of the sinking of the Lusitania on 7 May 1915

British War and Mercantile Marine War Medals 1914-18 (Christina C. Duncan), good very fine (2)

Christina Campbell Duncan was born in Kirkdale, Liverpool, on 8 March 1879, and followed her father, Andrew, into the Mercantile Marine, about 1910. Prior to her joining the Lusitania on her ill-fated voyage in 1915, she had gained lengthy experience as a stewardess plying the trans-Atlantic route.

In 1904, she married Basil George Rennie in her hometown, but the couple would appear to have separated in the period leading up to the Great War. They did not divorce. He served in the King's Liverpool Regiment for four years, before settling in Nelson, British Columbia in 1916, following his marriage to Elizabeth Kennedy and enlistment as a 2nd Lieutenant into the Canadian Army.

Lusitania

On 16 April 1915, Christina was engaged at Liverpool on board the Lusitania at a monthly rate of pay of £4-0s-0d, her previous ship being the Anchor liner Transylvania. She stated her age as 31, but she would have been 36 at the time, and she used her maiden name rather than her married name.

Launched in 1906 at a time of fierce competition for North Atlantic trade, the R.M.S. Lusitania was briefly the world's largest passenger ship and holder of the Blue Riband at 25.65 knots (47.5 km/h) from Queenstown to Ambrose Light in August 1909.

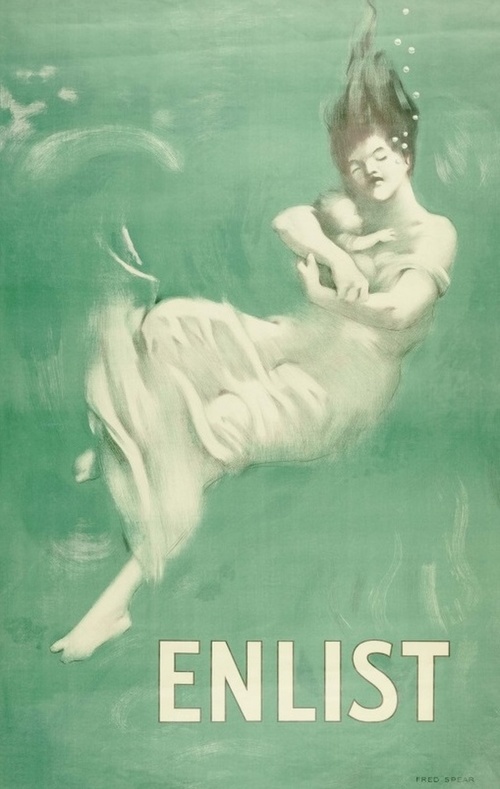

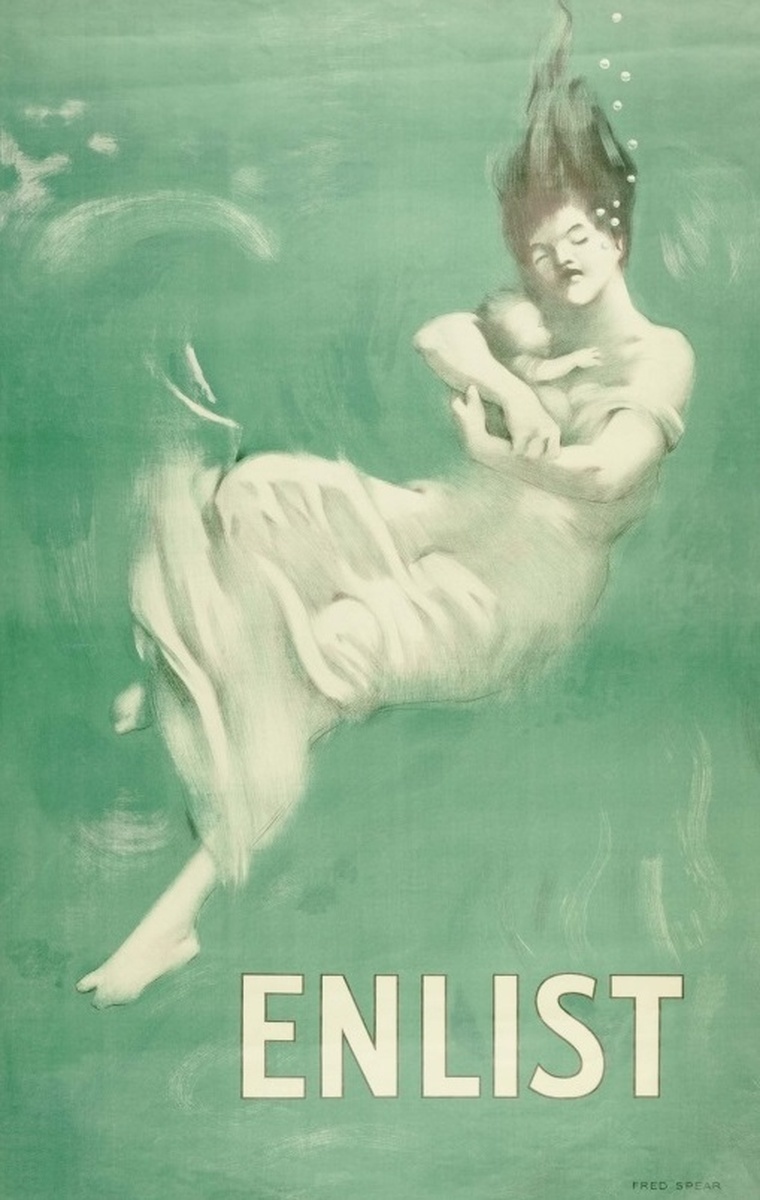

Lusitania set sail on her return trip to Liverpool - from New York - on 1 May 1915. As she departed, the docks were crammed with news reporters following the publication in the American papers of warnings from the German Embassy advocating that any ship that sailed into the 'European War Zone' was a potential target for German submarines. Some papers even went as far as to print the warning directly next to Cunard's list of departure dates. Regardless of this, the liner was packed with passengers, many of whom had come to the simple conclusion that a luxury liner simply was not a legitimate target as it had no military value. It was assumed that the likes of multi-millionaire Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt I and wine merchant George 'Champagne King' Kessler, would have access to information from the highest sources to warn them if danger really did exist. One female passenger is noted as remarking: "I don't think we thought of war. It was too beautiful a passage to think of anything like war."

On 4 May the Lusitania crossed the half-way point of her journey unhindered, but as she neared the Old Head of Kinsale, she was spotted by Kapitan Leutnant Walter Schwieger of the U-20. Since departing her base at Emden on 31 April 1915, the U-20 had been busy, having already made the mistake of attacking a Danish merchant vessel and relinquishing fire upon the hoisting of a Danish flag. On 6 May, the U-20 sunk the liners Candidate and Centurion, but it was at 13.40 hours on the following day that Schwieger spotted the Lusitania. He closed and fired a single torpedo.

According to Schwieger's log, at 14.10, 'Shot hits starboard side, right behind bridge. Unusually heavy detonation follows with a strong explosion cloud.' In the next entry he noted, 'great confusion on board … they must have lost their heads.' Chaos had indeed ensued for the torpedo had carved a gaping hole into the ship's side and the speed and steep angle of her sinking made it extremely difficult to launch the lifeboats - the first one to be lowered spilled its occupants into the sea. The ship sunk in less than eighteen minutes.

Of a total of 1962 persons on board, 1201 died, including 3 Germans held in the cells and 3 stowaways. Of 159 Americans, 128 perished, including Vanderbilt, and out of 129 children, 94 were drowned including 31 of the 35 babies on board. Of the crew of 693 men and women, just 291 survived.

In the days following the disaster, The Times referred to the sinking by condemning those who doubted German brutality: 'The hideous policy of indiscriminate brutality which has placed the German race outside the pale. The only way to restore peace in the world, and to shatter the brutal menace, is to carry the war throughout the length and breadth of Germany. Unless Berlin is entered, all the blood which has been shed will have flowed in vain.' To placate the Americans, German Command gave an informal assurance to President Woodrow Wilson that there would be no repeat of Lusitania, and the 'sink on sight' policy was called off on 18 September 1915: it was re-introduced on 1 February 1917.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£1,500