Auction: 16043 - Autographs, Historical Documents, Ephemera and Postal History

Lot: 116

Documents

France

Catherine de' Medici

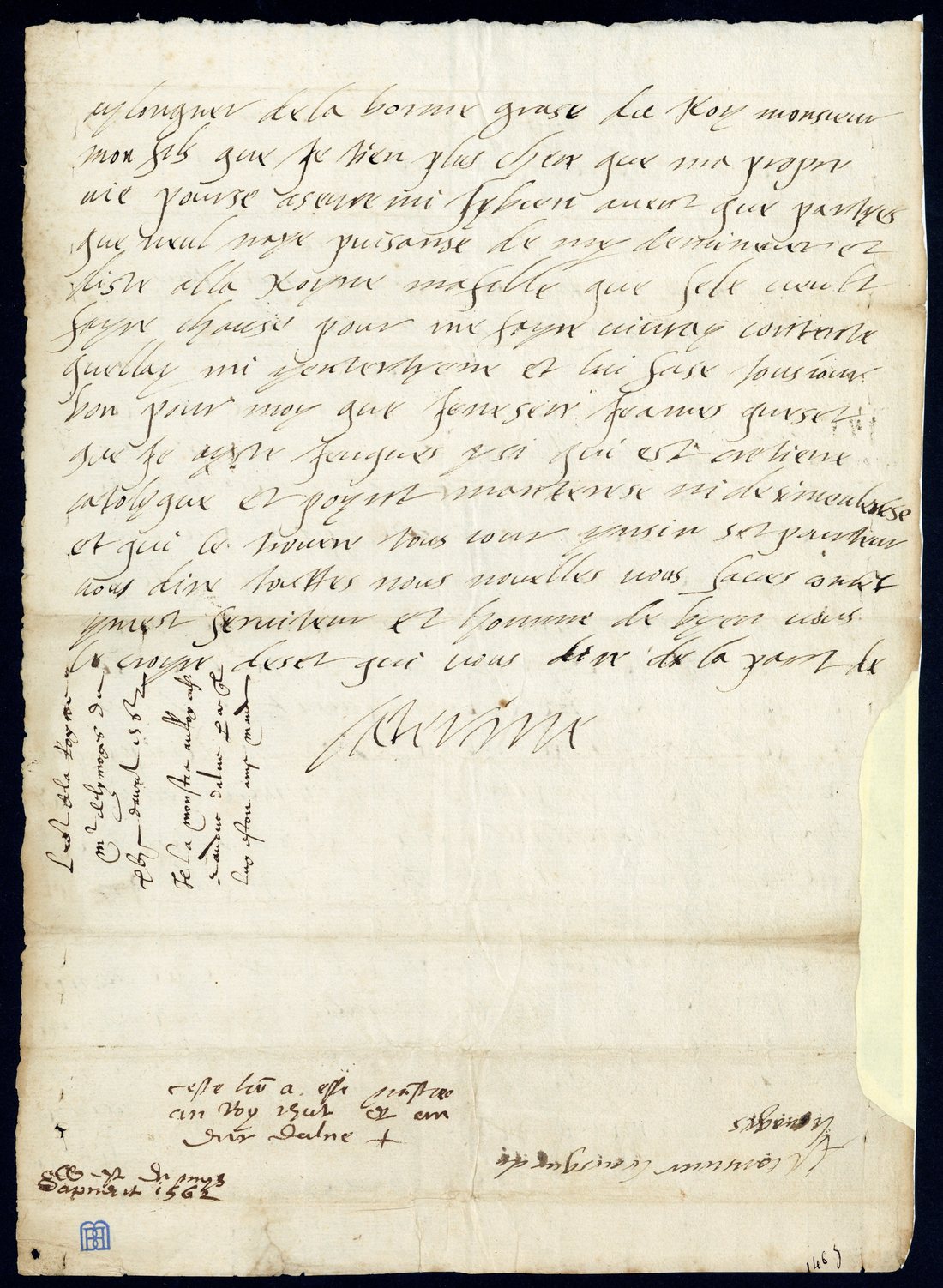

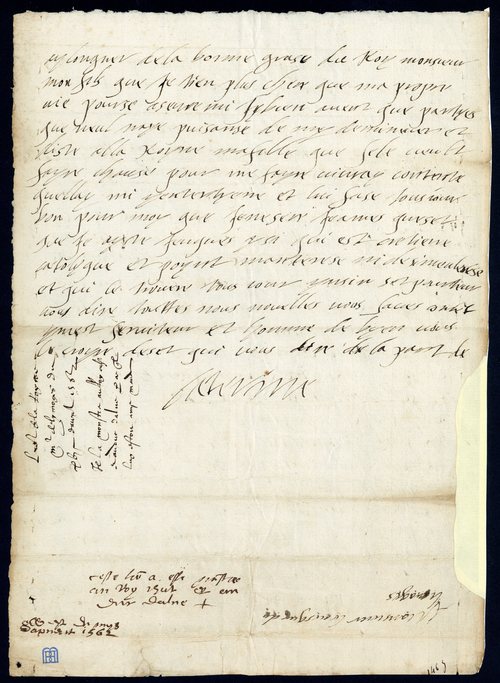

1562 (16 April) a fine A.L.S. which is signed "Caterine"; long letter to Sébastien de L’Aubespine (1518-1582), bishop of Limoges, her ambassador to the Spanish court (though actually written for the benefit of her son-in-law, King Philip II, and his wife, her daughter Elisabeth de

Valois), defending herself against the accusation of having converted to Protestantism. She asserts that she will stay what she has been the first 43 years of her life – a Catholic, not a liar or hypocrite.

"Monsieur de Limoge je byen voleu que tous ses signeurs aycripse au Roy despagne de la fason que je souis pour respet de la religion non pour temoignage se que je veulle ni devant dieu ni les hommes de ma fouys ni bonnes heuvres mes pour reguart de manterie que lons ha distes de moy et le calonnie que lon ma donnees. car set lons ha mande auparavent aultre chause que set que lon fayst asteure lons ha manti car je nay change ni en nefayst ni en volante ni en fason de vivre ma religion qui lya quarante et troys hans anuit que je tiens et hye aysté batisee et nourie et je ne se si tout le monde en peult dire aultent et set je an suis marrye ne san fault aybayr car set mansonge deure trop lontemps pour ne san facher a la fin et prinsipalement quant lon se sent la consiense neste y fayst byen mal que seus qui ne lon pas tent en parler et hardiment. monstre sete letre au duc dalbe et au Roy monsieur mon fils car ie ne voldres qui pansaset que jeuse mandie heun temoynage pour nestre alaye toutte ma vye le droyt chemin mes je lay fayst pour ne povoyr plus endeurer que lon me preste de cherite et que sela ferme la bouche a seus que disi ennavent san voldrest encore ayder et metre tousiour pouine de me aylongner de la bonne grase du Roy monsieur mon fils que je tien plus chere que ma propre vie. pourse aseure me sybien avent que partyes que neul naye puisanse de my demineuer et diste alla Royne ma fille que sele veult fayre chause pour me fayre vivray contente quellay mi y entertyene et lui fase tousiour bon pour moy que je ne sere jeames que set que je ayste jeuques ysi qui est cretiene catolyque et poynt manterese ni desimeuleuse et qui le truvere tous iour ynsin ... "

The notion that Catherine had supposedly rejected Catholicism may be due to the two edicts she issued for her under-age son Henry III in July 1561 and January 1562, probably under the influence of the moderate chancellor Michel de l’Hopital. The former repealed the death sentence for heresy; the latter – the Edict of Saint-Germain – granted Huguenots private worship outside of towns. Meanwhile, Francis, Duke of Guise, butchered some 80 Huguenot worshippers in the Massacre of Vassy, prompting the first of the French Wars of Religion. The politically talented and ruthless Catherine first attempted to maneuver a middle course between Protestants and Catholics in order to strengthen royal dominion. Only after the so-called "Surprise de Meaux" (1567), during which Louis de Bourbon tried to arrest Charles IX and the royal family, did she entirely abandon compromise for repression. Her pragmatic approach is underlined by the fact that she offered the Huguenot Henri de Navarre her daughter’s hand in marriage. While today some historians argue that the order for the 1572 St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre did not come from her, there is no reason to believe she was not party to the decision when on 23 August Charles IX ordered, "Then kill them all!"

Note of receipt by L’Aubespine at the bottom, "Lettre de de la Royne a Mr de lymoges du 16 davril 1562. Je la monstra au Roy et au duc dalve ...". The left edge remargined with slight clipping but no loss to text; traces of mounting. A very important letter which illustrates her endeavours to quell religious intolerance during this highly volatile time in European history, Photo

Catherine de' Medici (1519 – 1589), daughter of Lorenzo II de' Medici and of Madeleine de La Tour d'Auvergne, was an Italian noblewoman who was Queen of France from 1547 until 1559, as the wife of King Henry II. As the mother of three sons who became kings of France during her lifetime, she had extensive, if at times varying, influence in the political life of France. For a time she ruled France as its regent.

In 1533, at the age of fourteen, Caterina married Henry, second son of King Francis I and Queen Claude of France. Under the gallicised version of her name, Catherine de Médicis, she was Queen consort of France as the wife of King Henry II of France from 1547 to 1559. Throughout his reign, Henry excluded Catherine from participating in state affairs and instead showered favours on his chief mistress, Diane de Poitiers, who wielded much influence over him. Henry's death thrust Catherine into the political arena as mother of the frail fifteen-year-old King Francis II. When he died in 1560, she became regent on behalf of her ten-year-old son King Charles IX and was granted sweeping powers. After Charles died in 1574, Catherine played a key role in the reign of her third son, Henry III. He dispensed with her advice only in the last months of her life.

Catherine's three sons reigned in an age of almost constant civil and religious war in France. The problems facing the monarchy were complex and daunting but Catherine was able to keep the monarchy and the state institutions functioning even at a minimum level. At first, Catherine compromised and made concessions to the rebelling Protestants, or Huguenots, as they became known. She failed, however, to grasp the theological issues that drove their movement. Later she resorted, in frustration and anger, to hard-line policies against them. In return, she came to be blamed for the excessive persecutions carried out under her sons' rule, in particular for the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre of 1572, in which thousands of Huguenots were killed in Paris and throughout France.

provenance: J. P. Barbier-Mueller

literature: Lettres de Cahterine de Médicis, Hector de la Ferrière, Paris, 1880: vol. 1, p.296

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£7,500