Auction: 13003 - Orders, Decorations, Campaign Medals and Militaria

Lot: 29

The Historically Important Group of Honours and Awards Bestowed Upon Bwana Doctari Surgeon-Major T.H. Parke, Army Medical Department, A Doctor, Soldier, Explorer, and Naturalist, Who Served Alongside H.M. Stanley in the Advance Column as Medical Officer on the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition, 1887-89, in Which Capacity He Cared For and Saved the Lives of Both Stanley and Emin Pasha, While in the Process Becoming the First Irishman to Cross the African Continent

a) The Most Venerable Order of St. John, Officer's breast Badge, silver, with lions and unicorns in angles

b) Egypt 1882-89, dated, two clasps, The Nile 1884-85, Abu Klea (Surgeon. T.H. Parke. A.M. Dept.)

c) Zanzibar, Sultanate, Order of the Brilliant Star, Commander's neck Badge, 86mm including wreath suspension x 61mm, silver-gilt and enamel, with neck riband

d) Turkey, Ottoman Empire, Order of Medjidieh, Third Class neck Badge, 78mm including Star and Crescent suspension x 61mm, silver and enamel, with mint mark and silver marks on reverse, lacking obverse central medallion, with neck riband; together with the recipient's Fourth Class breast Badge, 65mm including Star and Crescent suspension x 50mm, silver, gold applique, and enamel

e) Khedive's Star 1882, unnamed as issued

f) Emin Relief Expedition Star 1887-89, silver (Hallmarks for Birmingham 1889), unnamed as issued, good very fine or better, with various damaged boxes of issue, two of which are embossed 'T.H.P.', and the following additional Honours and Awards &c.:

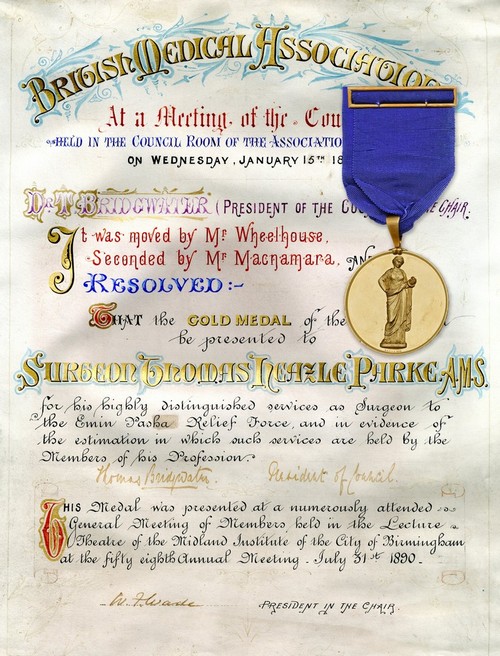

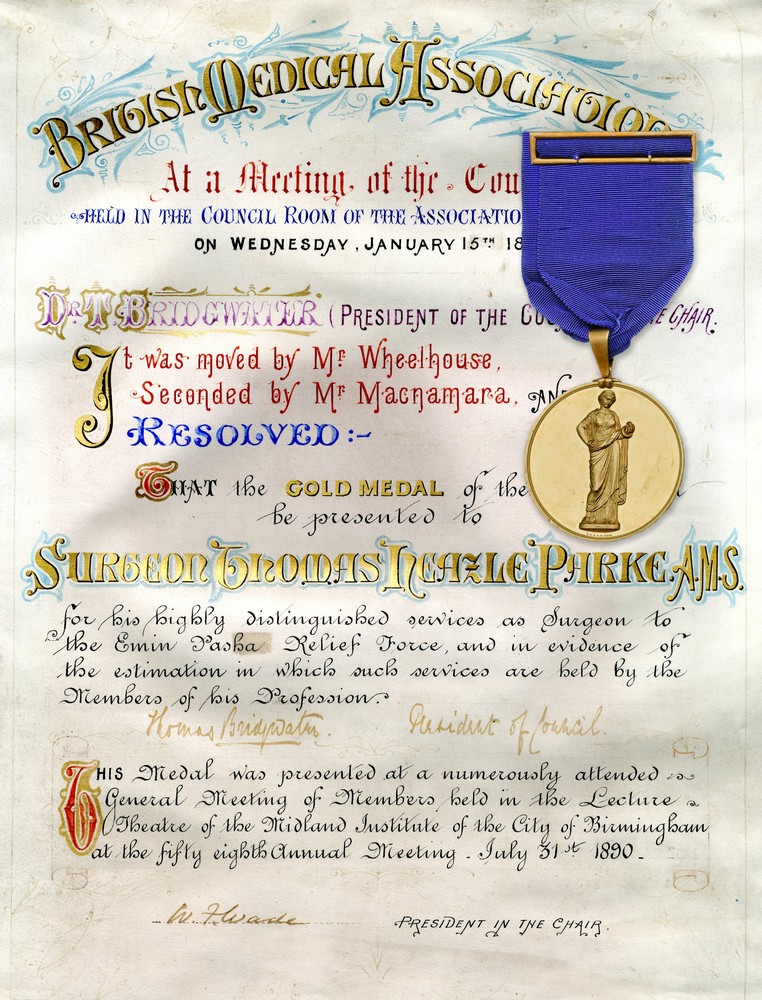

- British Medical Association Gold Medal for Distinguished Merit, by J.S. & A.B. Wyon, London, 57mm, gold (139.21g), Minerva on obverse, reverse inscribed 'For Distinguished Merit' within wreath, 'British Medical Association Medal Instituted July 11th 1877' around, edge engraved in large serif capitals 'Surgeon Thomas Heazle Parke, A.M.D., 1890.', planchet detached from suspension, with neck riband with gold buckle, in embossed fitted case of issue, with illuminated presentation Bestowal Document, named to Surgeon Thomas Heazle Parke, A.M.S., and dated 31.7.1890

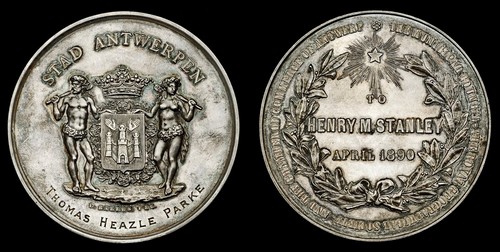

- Royal Geographical Society of Antwerp Stanley Medal, by F. Baetes, Antwerp, 66mm, silver, Antwerp city Arms on obverse, 'Stad Antwerpern' above, 'Thomas Heazle Parke' engraved below in sans-serif capitals, reverse inscribed 'To Henry M. Stanley April 1890' within wreath, Star above, 'The Municiple Council- The Royal Geographical Society- and The Chamber of Commerce of Antwerp' around, edge plain, in fitted case of issue, the lid embossed 'T.H.P.'

- Royal Geographical Society Stanley Medal, by Miss E. Hallé, London, 123mm, bronze, Stanley facing left on obverse, 'HM Stanley Presented by the Royal Geographical Society MDCCCXC.' around, reverse featuring a female deity wearing elephant head-dress and holding in each hand a vase from which water pours, her left foot resting on a crocodile, mountain scene in background, 'Congo, Nile, Rvwenzori 1887-1889' in upper right hand corner, the top engraved in large serif capitals 'Thomas Heazle Parke', edge plain, in fitted case of issue, the lid embossed 'T.H.P.'

- The Massive 'Americans in London' Tribute Medallion, by Elkington, London, 115mm x 105mm, silver (1.12kg, Hallmarks for London 1890), Stanley facing right on obverse, 'From Americans in London to Surgeon T.H. Parke, A.M.D. (Bwana Doctari) 30th. May 1891. "Skilled as a Physician, Tender as a Nurse, Gifted with Remarkable Consideration and Sweet Patience"- Stanley.' engraved below, reverse featuring portraits of Stanley's four principal Officers, Lieutenant W.G. Stairs, Surgeon T.H. Parke, Captain R.H. Nelson, and Mr. A.J. Mounteney Jephson in centre, Map of Africa above, with the Union and American Flags either side, forest and mountain scenes in background, '"Never while Human Nature remains as we know it will there be found four Gentlemen so matchless for their constancy, devotion to their work, earnest purpose and unflinching obedience to Honour and Duty"- Stanley.' engraved below, in fitted case of issue, the lid depicting a scene where 'Parke sucks the arrow poison from Stairs' wound', and embossed 'Surgeon T.H. Parke, A.M.D. (Bwana Doctari- Master Doctor)'

- THE AMERICAN TESTIMONIAL BANQUET TO HENRY M. STANLEY, IN RECOGNITION OF HIS HEROIC ACHIEVEMENTS IN THE CAUSE OF HUMANITY, SCIENCE & CIVILIZATION, London: no publisher, May 30, 1890. Octavo, original elaborately tooled full polished brown calf, patterned endpapers, all edges gilt, with five vintage prints of Stanley and his chief officers

- Page from the Will of Captain W.H. Parke, the recipient's heir, listing Parke's honours and awards

- Portrait photograph of the recipient, together with a photograph of the Men of the Expedition (lot)

Turkish Order of the Medjidieh, Third Class London Gazette 18.2.1890 Surgeon Thomas Heazle Parke, Army Medical Staff

'In recognition of the signal services which he has rendered, under the leadership of Mr. Stanley, in effecting the deliverance of Emin Pasha.'

Surgeon-Major Thomas Heazle Parke, was born in Kilmore, Co. Roscommon, Ireland in November 1857, and was educated at the College of Surgeons, Dublin. In February 1881 he was Commissioned into the Army Medical Department, and, having volunteered for active service in the Egyptian campaign, left England for Africa- the Continent which would form the backdrop to the greater part of his professional life- the following September. He was first stationed in Alexandria, 'where the exigencies of warfare, and the calls of pressing professional duties, did not prevent me from receiving a great deal of hospitable kindness and attention from the foreign residents of that venerable metropolis. In addition to the necessarily large proportion of bullet wounds, and the other surgical injuries connected with the use of modern weapons of destruction, I had there a very large medical practice in the treatment of malarial fevers, gastro-intestinal inflammations, and fevers of a purely enteric (typhoid) type. The enormous preponderance of intestinal diseases of every class, which is so characteristic of medical practice in sub-tropical climates, was well exemplified in my Alexandrian experience.' (My Personal Experience in Equatorial Africa as Medical Officer of the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition, by T.H. Parke refers). Such experiences were to prove a most useful introduction to Africa. As well as his practice in Alexandria, Parke saw a good deal of field service, including the surrender of Kafir Dowar, and received the Egypt Medal and Khedive's Star.

The Nile Expedition 1884-85

Returning home in late 1883, Parke was stationed at Dundalk, Ireland, until September 1884, when he again volunteered for active service, and joined the Nile Expedition for the relief of General Gordon. Arriving in Egypt on the 7th October 1884, he left Cairo for the front three days later. Appointed in Medical charge of the Naval Brigade, under Lord Charles Beresford, he crossed the Bayuda desert, was present at the Battles of Abu Klea, 17.1.1885, and Gubat, and the attack on Metammeh. Parke was one of the five Officers who crossed the Bayuda desert with Lord Charles Beresford: two were killed, one was severely wounded, Beresford was slightly wounded, and Parke himself escaped without a scratch. After the fall of Khartoum, he accompanied the Camel Corps as Medical Officer down the Nile to Alexandria, and prepared to return to England: 'We had actually got on board, and, just as the boat was moving off, I received orders to disembark, and return to duty at Alexandria. So I was obliged to have my few articles of baggage hastily brought back to land, and again resume my duty on the African continent.' (ibid).

The Emin Pasha Relief Expedition 1887-89

Following the fall of Khartoum to the Mahdist forces, Egyptian control over the Sudan collapsed, and the extreme southern province of Equatoria, located on the upper reaches of the Nile near Lake Albert was cut off from the outside world. The Governor of this province was Emin Pasha, a German doctor and naturalist who had been appointed Governor of Equatoria by General Gordon. Having been informed in February 1886 that the Egyptian government would abandon Equatoria, he wrote suggesting that the British government annex Equatoria itself. Although the government was not interested in further expansion in Africa at this point in time, the British public came to see Emin as a second General Gordon, in mortal danger from the Mahdists. A Relief Expedition, funded by public subscription, was hastily arranged, and the man approached to lead the expedition was none other the most famous African explorer of the age, Henry Morton Stanley.

An Invitation from Stanley

'28th-29th January 1887: I was dining with a party at the Khedivial Club when a telegram was brought to me by the waiter. On opening it I found it was from the leader of the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition. It was worded as follows:

"Surgeon Parke, Medical Staff, Alexandria. If Allowed accompany Expedition what terms required? Are you free to go with me? Stanley."

I determined to lose no time in preparation, as Mr. Stanley's quickness of resolve and promptitude of action were well know. So I immediately wired my reply:

"Certainly. Coming to Cairo tonight."

Upon meeting Mr. Stanley, I asked whether he had any surgical instruments with him for the use of the Expedition. He replied "No".' (ibid).

Parke spent the next week frantically procuring the required kit and supplies, as well as paying the necessary farewell visits. And on the 7th February 1887 the Expedition, consisting of Stanley, his servant, his six British Officers, together with 62 Sudanese and 13 Somali men, sailed for Zanzibar.

Arriving in Zanzibar on the 22nd February, Stanley recruited a further 600 Zanzibar men for the Expedition, before setting sail once more for the Belgian Congo. Passing Cape Town on the 9th March, they reached the mouth of the Congo on the 18th March, and proceeded slowly up the river, crossing the Equator on the 24th May, and finally reaching the navigable head of the Congo at Yambuya in mid-June. There they set up a base camp, which would be defended by the rear column, comprising of two of the six Companies, formed mainly of the weaklings of the Expedition, leaving four Companies, commanded by Parke, Lieutenant W.G. Stairs, Captain R.H. Nelson, and Mr. A.J. Mounteney Jephson, to proceed with Stanley in search of Emin Pasha.

Through Darkest Africa

'28th June 1887: Réveille sounded at 5:00am, and, one hour after, Mr. Stanley marched out of the stockade with the advance guard- at the head of the Column, which numbered 389 Officers and Men. We bade good-bye to Barttelot and Jameson, both of whom looked very gloomy at the idea of being left behind. When we marched away the place looked quite deserted, but the Garrison is well protected by the stockade. We kept to the river as we went on; and are to proceed directly east, to the southern extremity of the Lake Albert. Our march led us through the forest in a thick undergrowth of bush, through which we were obliged to cut our way. After a few hours' march some of the hostile natives fired upon us with their poisoned arrows. Every evening when we halt our first duty is to get the men to cut bushes and make a zareeba of considerable size and strength, so as to protect the caravan from night surprises, of either wild men or wild beasts. We then pitch our tents, pile the loads, and the men make their huts- all inside the enclosure. Rain fell heavily and drenched everything. All the rivers are so swollen that we are sometimes up to our necks in wading through'

'13th August: Stairs was wounded by a poisoned arrow. He was very much blanched; there was very little haemorrhage, but he was suffering greatly from shock and pain. I found a punctured wound on the left side of the front of his chest, just below the nipple: close to the apex of the heart. Just as he was hit, he had struck the arrow aside with his arm; this had the effect of breaking it off in the wound, leaving a couple of inches within the chest. As the arrow was a poisoned one I regarded suction of the wound as offering the best and only chance of life; for the point had penetrated much deeper than a caustic, applied externally to the wound, could possibly reach. Acting on the idea, I at once sucked the edges of the wound; till I felt sure that I had extracted the greater part, if not the whole, of the adherent poison. I then washed out my mouth with a weak solution of carbolic acid, and injected the wound with the same, before applying carbolised dressings to the wound, and bandaged the whole securely. He was now very faint, and of course very anxious, so I gave him half a grain of morphia by hypodermic injection.' (ibid). Parke had by now well and truly earned the epithet 'Bwana Doctari', meaning 'Master Doctor'.

The Expedition continued its course across the African continent, becoming more desperate as it went. Food was scarce, disease common, the weather and terrain awful. All five Europeans, including Parke and Stanley, were struck down by dysentery, and desertions amongst the Zanzibaris were increasing. By October all the men were in a fainting condition for want of food, and Parke was left wondering how it would all end:

'15th October: We are all exhausted now, and our men are in a desperate way. Mr. Stanley shot his donkey, and gave 1lb ration of flesh to each man. They were ravenous, and struggled like pariah dogs for the blood, hide, and hoofs. it is pitiful and painful, to the last degree, to see all the other appetites and passions completely merged in the overwhelming one of hunger. Hardly a trace of any other idea seemed to exist in the minds of our starving men than that of the mechanical introduction of food into the stomach.'

'16th October: we marched early, but there were not enough men to carry the loads, as the poor creatures were dying along the road, and we had to leave them, taking their rifles with us. Our philanthropic pilgrimage for the relief of our hypothetical friend, Emin Pasha, is certainly being carried out with many of the outward and visible signs of an inward and spiritual self-denial, which cannot, I venture to think, be very far surpassed in history.' (ibid).

Starvation and Fever in Ipoto

In late October the Expedition arrived at the village of Ipoto, which was to be Parke's home for the next few months:

'24th October: In the evening Mr. Stanley called us white Officers into his tent, and said that I am to remain here to look after Nelson, and that Stairs and Jepson should follow him with all available men. I asked him when I should be relieved. He said three months hence; that I should be brought away with Nelson. Practically we will both be prisoners here. I asked to get the native chiefs to agree that we should be fed. He replied that he had done so, and made arrangements to this purpose, but that we should probably get little or no meat. So that we have no prospect before us here but an indefinite period of vegetarian existence.'

'27th October: Mr. Stanley marched away this morning with 147 men. I am now left here with 29 starving Zanzibaris. A dismal prospect, at the mercy of these savages, my 29 men lying all about everywhere- bags of bones as they all are.' (ibid).

Over the next two months relationships with the villages went steadily downhill, and it was only through selling their clothes, rifles, and ammunition that Parke and his men were able to get even scraps of food. The situation became steadily worse:

'15th December: Spent the day in bed, as I am unable to walk on account of enlarged glands in the upper part of the front of my left thigh. I calculate that it will lay me up for a month, and that I will have to use the knife on myself. An inspiring anticipation, surely, under my circumstances. There is a very great inflammatory swelling about my left hip and thigh, with a decidedly erysipelatous-looking blush, and an accompanying temperature of 100F. I am sure I have got blood poisoning from the continual handling of the ulcers from which so many of our men are suffering, and the condition is necessarily aggravated by the results of the wretched dieting to which I have been so long obliged to accommodate myself. A most lovely sunset this evening. One would like to be able to enjoy it, but the surroundings are rather against the full appreciation of aesthetic effects.'

'17th December: I am worse today, the inflammation is spreading up the walls of the abdomen, and down the left thigh, and the scarlet hue of the surface has been exchanged for a deep livid tint. The surface pits on pressure, and there is intense pain. No position is comfortable for me. I injected some cocaine, with the intention of making an incision to relieve the extreme tension; but I postponed (or rather "funked") the latter performance till tomorrow.'

'19th December: Nelson is very weak- so far gone indeed that he will certainly die if he is attacked by any acute disease, as he has no strength left to bear up against it, and there is no nourishment to be procured for him by any means I know of. It is really heartrending to look on at his declining condition fading as he is day by day. I gave myself a large injection of cocaine, as a local anaesthetic, and Nelson operated on me. He made an incision about two inches in length, and two in depth, then quickly disappeared from my tent. A very profuse haemorrhage followed, which weakened me considerably. I was to have had two incisions, but the one that he gave me was as much as I cared to experience. Poor fellow! He used to be called by the men "Panda lamwana" meaning "big man", on account of his size and strength, and now he is reduced to a walking skeleton of 135lbs.'

'20th December: We were obliged today to give a Remington rifle to a chief for a goat, so as to have some meat for Christmas. We also bought a lot of insects- they look half bee and half grub- which are found in the soil here, and are said to be a luxury. At this rate we can hold out but for a month or so; Mr. Stanley says we may be relieved after three months!'

'25th December: I spent the day in bed, lying on our ammunition boxes. My temperature was 102F, and my erysipelas worse. The latter is now extending down the left leg. I am greatly afraid that this thing will keep me on my back for a long time. Nelson, I am glad to say, is now better. He superintended the dinner, which consisted of goat and rice. I wish all my friends at home a happier Christmas that I myself can enjoy. Another month, and all our Zanzibaris will be dead from starvation. Twelve have disappeared already of the 29 we were left, and I feel certain that some of them have been eaten by the villagers. We have been saved up to the present from a similar fate by judicious disposal of our clothes and rifles.' (ibid).

The New Year hardly brought any comfort, and January in particular was a wretched month for both Parke, whose erysipelas got worse, and Nelson:

'23rd January 1888: We are in a bad way for food- the chiefs seem to think that we have no stomachs. We are all skeletons- neither Nelson nor myself can walk more than a few yards at a stretch. Last night one of the men went down to the river to draw water- a distance of about 200 yards from the village. He was set upon by his comrades on the way, and killed and eaten there and then. Food now seems to be really scarce indeed! The people are now existing, in great measure, on banana and plantain root, which is very stringy and tasteless. The river, from which we draw our drinking water, is polluted with excrement.' (ibid).

But help was, finally, around the corner:

'25th January: At 11:00am one of the native chiefs came and said that his sentries had come in, and told him that a white man was coming- many shots were fired off, and a drum was beaten, to hail the advent of the stranger. We could scarcely speak for joy, as we anticipated some relief from our dreary existence of imprisonment and starvation. After a few more minutes Stairs appeared, leading a column of the finest looking, fat, muscular, glossy-skinned men I ever saw, the same men who had left us in skeleton form three months ago. They cheered, and we cheered; they fired a volley, and both Nelson and myself fired off every chamber of our revolvers in salutation. It was a moment of excitement, a reprieve from the death sentence which we had so long felt pressing over and around us. Stairs told us what had happened since we had parted; how they had found food at a distance of ten days from here, and that Mr. Stanley and Jephson are working hard at Fort Bodo, but still without news of Emin Pasha. He was delighted to see us, and our joy to have him back can hardly be described. He really is a good hearted fellow, and did not neglect to bring us plenty of food. We sat up late to prolong our rejoicings; and altogether I felt that this relief was the happiest event of my life. I had said several times, lately, to Nelson that I believed Mr. Stanley would rescue us before the three months were ended.' (ibid).

After setting out the following day, Parke and Nelson reached Fort Bodo, Stanley's new camp, on the 8th February.

A New Patient- Stanley Himself

'18th February: I was sent for at 3:00am to see Mr. Stanley. He was suffering from great pain in the epigastric region; and, indeed, apparently over the whole surface of the abdomen, with a good deal of hepatic tenderness, especially in the vicinity of the gall bladder. He said that it is the same illness which had brought him to the brink of death on three former occasions. So he is naturally very anxious about the result.'

'19th February: The illness of our chief was, of course, my great care today. I kept him on an exclusive milk-diet. The milk was always given cold, and diluted with almost equal quantity of water. There is still great pain and tenderness over the stomach, accompanied by very distressing vomiting of a dark fluid. The rejected matter is evidently stained with some blood. I applied turpentine stupes, and gave forty minims of tincture opii by mouth, followed, as the retching continued, by half a grain of morphine, administered hypodermically. The latter gave great ease. I sat with him all night and all day; the vomiting continued, at short intervals, all the time. The tongue is covered by a thick white fur, and the skin is bathed in a profuse clammy perspiration. The pulse and respiration are both very rapid: he has fever, which is now assuming an intermittent type.'

'20th February: Mr. Stanley still very ill, and suffering intense pain, so that I now give a large dose of morphine morning and evening. I am keeping turpentine stupes constantly applied.'

'21st February: Jephson sat up last night with Mr. Stanley, as I was knocked up for want of sleep; having sat up two nights in succession. He feels a little better now, but I am still very anxious about him. His pulse is extremely quick and weak, and his entire condition very unpromising. There is no doubt that the case is one of sub-acute gastritis, with intense congestion of the liver and spleen. He cannot sleep, night or day, till he has had a large dose of morphia. The pain recurred badly this evening, so I gave a hypodermic dose of morphine, with a corrective of atropine. I also gave him bismuth and bicarbonate of soda in his milk. He is feeling easier tonight, but is extremely weak.'

'22nd February: I sat up the whole of last night, continually applying warm stupes over the stomach and liver. For food I gave him milk and water only. He had his first good sleep tonight, and feels somewhat stronger today, but it is still touch and go with him; he is excessively weak, even now. His tongue is still heavily coated with fur.' (ibid).

Over the next three weeks Parke slowly nursed Stanley back to good health, and by the 15th March he was up and about. On the 2nd April the Expedition left Fort Bodo for Lake Albert. The force at this stage numbered 122. Stanley was accompanied by both Parke and Jephson, leaving Nelson in charge of the Fort, with instructions that Stairs, when he was able, should follow on. On the 17th April they reached the Lake: 'Our chief sent me ahead of the column, to find the nearest point of emergence from the forest, which I did, thus ending my own forest existence of nearly twelve months. It did feel as a deliverance: I felt like Bonnivard when, after six years of dungeon life in the Castle of Chillon, he was again able to look over his beautiful and beloved Lake Geneva... The following day, after a march of about six miles, we were met by a native, who brought a letter addressed to Mr. Stanley, and signed "Dr. Emin".' (ibid).

Meeting with Emin Pasha

The letter from Emin Pasha to Stanley told how the writer had heard of Stanley's presence in the area, and asked that the Expedition stay where it was, as he would soon come down the Lake in his steamer. A week later a further missive arrived, saying that Emin would arrive on the 29th April:

'Everyone was on the qui vive to try and be the first to sight the steamers. Each of us tried for an elevated spot so that he might have a good point of view, and everyone strained his eyes to the utmost. Mr. Stanley got a good vantage point by utilising the summit of an ant-hill, on which he stood and used his binoculars. He was, accordingly, the first to announce "Steamer!" at about 5:00pm- she was then about seven or eight miles off. As the vessel came closer within range the Zanzibaris became perfectly wild with excitement. They were overjoyed with the certainty of the existence of the mysterious white man, in search for whom they had wandered so far and suffered so much- an existence the fact of which they had often bitterly questioned in the course of their weary wanderings through the forest. The steamer anchored in a bay about two and a half miles away. Mr. Stanley dispatched me with an escort to receive the Pasha and conduct him to our camp. It was pretty dark by the time I got near the place where the steamer was anchored, so I fired off a couple of volleys, on hearing which the Pasha came towards us. Our men displayed their sense of the triumphant issue of our wanderings by firing several volleys. It was not the least dangerous stage of our mission this- the Pasha's men were so excited that they let off their bullets in all directions, and at every angular elevation, so that a good many whizzed by, unpleasantly close to our heads, as we moved about in the dark.

The Pasha was of a very slight build, and rather short of stature. He wore a clean white shirt, with a spotless coat and trousers. His bronze skin and black hair were shown out in strong contrast by these garments. He looked cheerful and was excessively polite. The meeting between him and our leader was a warm one. Mr. Stanley gave the Pasha a seat, and then disappeared for a moment, returning with three bottles of Champagne, which he had been keeping carefully concealed in the lower depths of his box. We then all drank the Pasha's health. The Pasha said that he could scarcely express his thanks to the English for sending him relief at the expense of so much trouble and cost, but added that he did not know whether he would care to come out, after doing so much work in the province, and having everything now in perfect order... he seems to look upon himself as the slave of his people, and that his services are entirely theirs, to be used as they may think proper. He must have been an ideal liberal governor!' (ibid).

Almost a month went by, and still Emin Pasha would not decide whether or not he wanted to come out with the Expedition. On the 24th May, Stanley and Parke left Lake Albert, leaving Jephson with Emin Pasha, to return to Ipoto, where Parke had spent such a harrowing three months, so that Parke could return to Fort Bodo with the stores that had been left behind there, whilst Stanley himself would continue back to the Congo, and bring up the Rear Column, still based there. Arriving at Fort Bodo on the 8th June, they met up again with Stairs and Nelson, who had both been stationed there, and rested for a week, before heading on to Ipoto, arriving there on the 23rd June;

'On my arrival, all the chiefs got up and came forward to meet me, and made their salaams. One of the chiefs asked me if I was ill; this, I knew by his subsequent conversation, was to introduce a contrast between my present appearance and what it had been when I left their camp. He said that I was fat and well then! In the afternoon Mr. Stanley abused the villagers pretty strongly for- as he directly put it- killing our poor Zanzibaris. The chiefs implored him not to tell the Sultan of Zanzibar of the cruelties that had been practised on the men during their stay, or of their treatment of Nelson and myself. My loads were all handed over correctly to me, and the following day Mr. Stanley parted from me to go towards Yambuya in search of Barttelot.' (ibid).

After an uneventful march, Parke arrived back at Fort Bodo, with all the stores, on the 6th July. Here he gathered his thoughts:

'8th July: I am indulging this evening in a somewhat gloomy retrospect. 29 men had been left with me originally at the Ipoto camp, and of this number half have now died. Nelson and myself remained in bed all today; we have both been attacked with bad fever. Providence does not appear to intend that any nook of Africa should afford us a haven of rest; alternate drenching by rain and combustion by fever fill up our present programme.' (ibid).

The next six months were to bring little change. Life at the Fort was a constant battle between fighting bouts of fever and scouring for food, ensuring what little crops they were able to cultivate were not destroyed by either elephants or native tribes. Their diet consisted almost entirely of bananas, beans, corn, and rice, together with what native herbs and other seasoning they could muster. All attempts at killing game were unsuccessful. Hopes that the tedium would be relieved, either by the arrival of Jephson with Emin Pasha, or by Stanley with the Rear Column, went unfounded until December.

Arrival of the Rear Column

'20th December: At about 10:00am we were interrupted by the report of shots fired at some little distance- the signal of Stanley's arrival with the Rear Column! We were emancipated from our wretched bondage! Stairs had mounted the sentry-box, and shouted that Stanley was coming. Nelson came out to the entrance of the Fort, and all the men began to jump about in a state of ecstasy. I ran down to meet him, and grasped his hand. He looked careworn and ragged to an extreme degree- and I never felt so forcibly as now, how much this man was sacrificing in the carrying out of a terrible duty which he had imposed upon himself. He might very well have been living in luxury within the pale of the most advanced civilisation, housed in some of its most sumptuous mansions, and clothed in its choicest raiment, and- here he was. I had never before so fully believed in Stanley's unflinching earnestness of purpose, and unswerving sense of duty.

I asked him how Barttelot and Jameson were, and he replied that they were both gone: Barttelot was shot on the 18th June, at Banalya, by a chief, for interfering with his wife; and Jameson had left for Stanley Falls for carriers and had not returned [It was later established that Jameson had died on the 17th August 1888 in the Belgian Congo of fever and exhaustion]. Of the 260-odd Zanzibaris, who had been left with the Rear Column, considerably less than 100 had survived to tell the melancholy tale.'

'We all now packed up our belongings, preparing to start for Lake Albert. In the evening we three whites (of the Fort) discussed the facts of the Expedition. We had been horrified by the story of the wreck of the Rear Column, which we had left in June last year, well secured in a stockaded fort at Yambuya. About one-third only of the force had survived; and enormous amount of baggage and ammunition had been lost or abandoned; and the Europeans appeared to have been completely at loggerheads with one another, and on extremely bad terms with their men.'

'23rd December: Mr. Stanley, Stairs, and myself left the Fort on our way to Lake Albert. Nelson remained behind for some hours with thirty men, to burn the Fort, to bury a large glass bottle at the eastern extremity of the enclosure, and then to bring on some loads. The glass bottle was buried a couple of feet underground, and contains a letter written by Nelson, and a few small things of European manufacture, which may teach the African antiquarian of a thousand years hence that a crude form of civilisation, known as the "English", had penetrated into the heart of Africa, in the year of grace 1888.' (ibid).

Further News from Emin Pasha

Arriving at Lake Albert in late January 1889, Stanley received a package containing letters from both Jephson and Emin Pasha. They contained the startling tale that Emin Pasha and Jephson had been made prisoners in August 1888 by mutinous rebel forces in Rejaf, in the north of the province. However, by luck, the Mahdi's troops from Khartoum came up the river in steamers, and attempted to capture Rejaf; in the confusion that ensued, the Pasha and Jephson took the opportunity to escape, and succeeded in reaching Kavalli Camp on Lake Albert. Emin Pasha concluded his letter by saying that his mind was now made up, and that he would accompany Stanley out of Africa. The Expedition now moved to Kavalli Camp with all haste. A successful conclusion was in sight!

'18th February: We started early, and, after a march of about eight miles, reached Kavalli's, where we were received by Emin Pasha. The Pasha now told us that he had not wished to come out, till the mutiny had occurred. Jephson is looking well; he suffered very little from fever during his stay with the Pasha.' (ibid).

For the Coast

After a two month wait at Kavalli's, whilst they waited for Emin Pasha's men to fall in, and also to make final preparations for the march to the coast, the Expedition left Kavalli's Camp and Lake Albert on the 10th April. Progress was painfully slow, as often one or more of the Officers were struck down with fever, and Parke, when he was not ill himself, was constantly tending to their needs, but finally, on the 16th August, Lake Victoria was spotted. On the 28th August they reached Usambiro, at the southern tip of Lake Victoria, where the Church Missionary Society had a station:

'28th August: We arrived here about 11:00am, and ate up everything we could lay hands on, in the shape of food. Mr. Mackay [the Missionary] was most cordial and generous, and threw open all his stores to us. We also enjoyed the first European news we had heard for nearly two and a half years. Our first question was whether Her Majesty the Queen was still alive; then H.R.H. the Prince of Wales; then the Princess of Wales. We heard of two dead Emperors of Germany; and no military campaigns. Our latest newspaper is February 1888, so that we only got the news of "The Failure of the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition"- printed while we were working hard and doing well!

We also heard of the German activity in the interior. When we started with the Expedition, we were constantly chaffing the Zanzibaris by telling them that the Germans would have Zanzibar when we returned. It is really curious that our frivolous jokes should have been verified so truly.' (ibid).

Having crossed the African Continent from west to east, the Expedition arrived at Bagamoyo, on the shore of the Indian Ocean, on the 4th December 1889: 'The sight of the broad expanse of ocean called forth shrieks of joy from our impulsive Zanzibaris. My own eyes were not in good enough condition to enjoy the sight so much as I could have wished, but I felt, perhaps, nearly as much as any. The bitterness of death was past, our slow and weary pilgrimage had drawn to a close!'

'5th December: The local magnates, vice-consuls &c. (English, Germans, and Italians), welcomed us, and the Germans entertained us in the evening, with the object of doing honour to the long-lost Pasha and the hero of his rescue. A brilliant congratulatory speech was made by Major Wissmann, the German Commissioner, to which Mr. Stanley replied; and Emin Pasha expressed his grateful appreciation of what had been done for him by Mr. Stanley and ourselves, as the representatives of British philanthropy, in an eloquent and highly-finished discourse. All went merry as a marriage ball. After this speech he walked round to the back of my chair, full of spirits, spoke something in my ear, and strolled, evidently in an absent and contemplative mood, through a doorway towards the open window of an adjoining room.

He had occupied one-storey dwellings only, for a period of 14 years, and he simply walked through and was precipitated to the ground, a fall of about eighteen or twenty feet. The fall produced immediate unconsciousness. He had extensively fractured the base of the skull, and remained perfectly comatose for nearly five hours. He was at once conveyed to the German Hospital, where I myself attended to him. On recovering consciousness the first word he uttered, on partial recovery of the power of articulation, was "Parke". I was, naturally, a good deal affected by this indication of the impression I had made on my poor patient's feelings, and felt myself bound to him by a new tie of friendship.' (ibid).

Stanley himself left with the rest of the Expedition for Zanzibar on the following day, 6th December. Parke stayed looking after Emin Pasha for a further three weeks, until the Pasha had made a full recovery, before re-joining the rest of the Expedition in Zanzibar. Here he was suddenly struck down with malaria, and the doctors in the French Hospital feared the worse: 'The Doctor completely lost all hopes of my recovery, and on one night, when I was at the worst, he summoned Mr. Stanley, and my brother officers of the Expedition, to see me breathe my last. Prostrate as I was, I was conscious of their presence. My clearest remembrance on the subject are connected with the fact that, during my illness, I practically lived upon iced Champagne, and my sense of taste was never so completely benumbed as to prevent me from appreciating it. After three long years of indulgence in the sipping of stagnant, fetid, tepid, typho-malarial African water, the promotion to the enjoyment of such nectar as this was almost worth the illness which confined me to its use. To the leader of our Expedition, and to my brother officers, I owe a life-long debt of gratitude for their kind attention and assiduous care during my worst hours of sickness.' (ibid).

Home at Last

Parke left Zanzibar with Stanley and, after a few months in Cairo, returned home in triumph in April 1890: 'A large and enthusiastic crowd awaited at Alexandria to bid us "God speed", and to cheer us as we passed along, and we waved, as we moved away from land, a farewell salute to the shores of the continent, from the unexplored interior of which each one of us had, I believe, at some period of the Expedition, lost all hope of returning.' (ibid).

On their return Stanley and his four surviving Officers of the Expedition received tremendous public acclaim, and Parke was appointed an Honorary Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, and awarded the British Medical Association's Gold Medal for Distinguished Merit, as well as receiving the Ottoman Order of the Medjidieh (the Emin Pasha nominally and ultimately being a representative of the Sultan) and the Zanzibari Order of the Brilliant Star. As Stanley himself said of his Officers, 'Never while human nature remains as we know it will there be found four gentleman so matchless for their constant devotion to their work, earnest purpose, and unflinching obedience to honour and duty. I consider this Expedition was nothing happier than in the possession of an unrivalled physician and surgeon, Dr. T.H. Parke. Skilled as a physician, tender as a nurse, gifted with remarkable consideration and sweet patience, every white officer in the Expedition and Emin Pasha are all indebted to him.'

Promoted Surgeon-Major in February 1893, Parke died in Scotland later that year, his coffin brought back to Ireland for burial in his native land. A bronze statue was erected in his honour and stands on Merrion Street, Dublin, outside the Natural History Museum; and his papers are in the Library of the Royal College of Surgeons, Dublin.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£46,000