Auction: 13003 - Orders, Decorations, Campaign Medals and Militaria

Lot: 7

The Unique and Extremely Well Documented 'Defence of Legations' D.S.O., 'Great War' O.B.E. Group of Eleven to Lieutenant Colonel F.G. Poole, East Yorkshire Regiment, Later Middlesex Regiment, Who Commanded the International Volunteers in Peking and Was Wounded During the Defence; His Most Graphic Diary, and That of His Brother, Dr. Wordsworth Poole, Provide Great Historical Insight into Their Adventures in Africa and China

a) Distinguished Service Order, V.R., silver-gilt and enamel, with integral top riband bar

b) The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, 1st type, Military Division, Officer's (O.B.E.) breast Badge, silver-gilt (Hallmarks for London 1919)

c) Central Africa 1891-98, 2nd type, one clasp, Central Africa 1894-98 (Lt. F.G. Poole. E. York. R.), officially engraved in upright serif capitals

d) China 1900, one clasp, Defence of Legations (Capt F.G. Poole, D.S.O. E. York Rgt:), officially engraved in sloping serif letters

e) India General Service 1908-35, G.V.R., Calcutta Mint, one clasp, Abor 1911-12 (Captain F.G. Poole D.S.O. 2d. Bn: East Yorkshire Regt.), officially engraved in sloping serif letters, partially officially corrected

f) 1914-15 Star (Major F.G. Poole. D.S.O. Midd'x R.)

g) British War and Victory Medals, M.I.D. Oakleaves (Major F.G. Poole.)

h) Jubilee 1935

i) Cadet Forces Medal, G.VI.R. (Cadet Col. F.G. Poole. D.S.O. O.B.E.)

j) Turkey, Ottoman Empire, Order of Osmanieh, Fourth Class breast Badge, 80mm including Star and Crescent suspension x 63mm, silver-gilt, silver, and enamel, with rosette on riband, clasp backstraps removed on medals to facilitate court-style mounting, lacquered, generally nearly extremely fine, a unique combination, mounted court style and housed in a Spink, London, fitted leather case, the lid embossed 'F.G.P.', and with the following related items and documents:

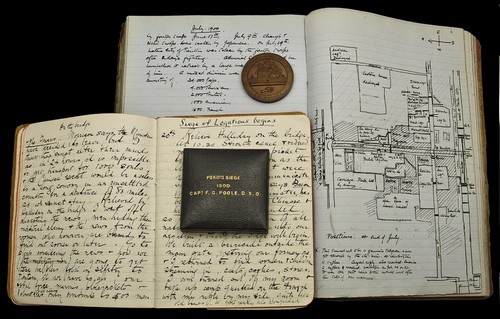

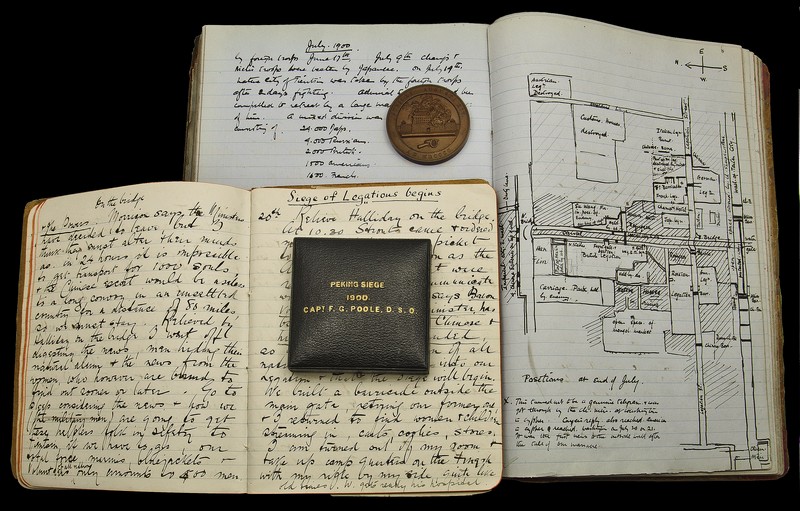

- Peking Siege Commemoration Medal 1900, by J. Taylor Foot, 57mm, bronze, obverse showing the Ch’ien Men engulfed in flames, with the cannon 'Betsy' below, and the inscription 'Junii XX - Augusti XIV, A.D. MDCCCC'; reverse showing the personifications of Europe, America, and Japan clasping hands, trampling on the Imperial Chinese Dragon, and the inscription 'Mene, Mene, Tekel, Upharsin. Ichabod!', the edge impressed 'Captain F.G. Poole. D.S.O.', (ref. BHM 3672), in fitted leather case of issue, the lid embossed 'Peking Siege 1900. Capt. F.G. Poole, D.S.O.'

- 'Diary in Peking', the recipient's hand-written diary of his time in Peking, covering the period 20.5.1900 - 10.10.1900 in detail, with some later sporadic entries from 10.12.1900 - 31.12.1901, with various sketch maps

- 'With the Abor Expeditionary Force', the recipient's account of the Expedition written under the pseudonym 'Wanderer' for 'Blackwood's Magazine', privately bound

- Copies of various Confidential Intelligence Reports written by the recipient, including 'The German as a Campaigner in China'; 'Report on a Journey to Constantinople, via Sofia to Belgrade, to the Iron Gates of the Danube, thence into Hungary, 1906'; 'Notes on a Journey in Tripoli, Tunisia, Algeria, Tangiers, and Casablanca, 1908'; 'The French North African Cavalry, 1908'; 'Notes on a Journey in Palestine, Syria, Asia Minor, Turkey, the Black Sea, and Caucasia, 1909', together with various letters of acknowledgement from Whitehall and Simla

- Copy of The Die Hards, The Journal of the Middlesex Regiment, March 1951, containing the recipient's obituary

- Various photographic images of Peking at the time of the Siege

Peking Siege Medal and Diary of Dr. Wordsworth Poole, C.M.G., Physician to the British Legation

- Peking Siege Commemoration Medal 1900, by J. Taylor Foot, 57mm, bronze, the edge impressed 'Dr. Wordsworth Poole. C.M.G.'

- Two Volumes of the recipient's hand-written Diaries, covering the period 14.1.1896 - 29.11.1901, detailing his time in Africa and Peking up until his death, with various sketch maps (lot)

D.S.O. London Gazette 25.7.1901 Captain Francis Gordon [sic] Poole, the East Yorkshire Regiment

'In recognition of services during the recent operations in China.'

O.B.E. London Gazette 3.6.1919 Poole, Maj. Francis Garden, D.S.O., Midd'x R.

'For valuable services rendered in connection with military operations in France.'

Turkish Order of the Osmanieh, Fourth Class London Gazette 28.6.1910 Captain Francis Garden Poole, D.S.O., East Yorkshire Regiment

'In recognition of valuable services rendered.'

Lieutenant-Colonel Francis Garden Poole, D.S.O., O.B.E., was born 24.6.1870, the younger son of the Reverend S.W. Poole, M.D., of St. Mark's, Cambridge, and was educated at Cambridge and the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst. Following Sandhurst, he was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the East Yorkshire Regiment, 20.2.1892, and was promoted Lieutenant, 1.3.1896.

Service in Central Africa

In January 1896, Poole's elder brother, Dr. Wordsworth Poole, joined the Administration of the British Central Africa Protectorate as Second Medical Officer. Within a fortnight of his arrival at Zomba, the capital of British Central Africa, he had received a letter from his brother, who at the time was in Cairo, enjoying his first taste of the African Continent. The opportunity for Francis to join his elder brother soon arose: 'Edwards' [Major C.E. Edwards] scheme of 8 Officers has received H.M. Commissioner's sanction. Edwards greatly delighted to be able to say that he has 8 Officers under him. I wrote to Francis telling him of this, and that Edwards will ask for him at the War Office so that it is very possible that Francis will be out here this year' (Dr. Wordsworth Poole's Diary, dated 4.2.1896, refers). By June 1896, Francis's appointment appears to have been confirmed: 'New mail came in- letter from Aunt Isobel regarding gun. She is sending a .500 out with Francis' (W.P. Diary, 22.6.1896 refers). Francis himself arrived at Zomba at the start of December: 'Francis arrived at night with his Zanzibari. Looks and says he is fit. Delighted to see him, he has later news of home than I have.' (W.P. Diary, 2.12.1896 refers). A week later, 'Francis left for Fort Lister. He is to raise of Company there' (W.P. Diary, 11.12.1896 refers). The Company that he succeeded in raising ultimately formed part of the 1st Battalion, Central African Rifles, the fore-runner to the famous King's African Rifles.

Early in 1897, Francis Poole, like almost all the Europeans in Central Africa, was struck down by fever: 'Last night news came that Francis at Fort Lister had a bad go of fever. Temperature 105 and delirious, so early this morning I left, not in the most cheerful of spirits. In fact there was a heavy feeling that I should not find him alive when I got there. Arrived and found Francis very weak and slightly delirious. Had a temperature of 106.' (W.P. Diary, 4.1.1897 refers). 'A terrible day- his throat filled with mucus, there were muscular tremors, his jaw dropped, and a hoarse cry came out from his throat. Temperature 107.2. I thought it was the end. What would mother and father say if he died, and I felt responsible for him having got him out here.' (W.P. Diary, 5.1.1897 refers). Fortunately though, Francis slowly recovered, and by the 15th January was well enough for Wordsworth to return to Zomba. Francis himself remained with his Company at Fort Lister, and served with them in August of that year against Chief Serumba of the Anguru, during the Lake Chilwa Expedition in Central Africa, and in January and February the following year in operations against Paramount Chief Mpezeni of the Ngoni tribe in North Eastern Rhodesia, receiving the Central Africa Medal.

Plans for China

Dr. Wordsworth Poole returned to England on leave in June 1899, having spent the past 18 months serving as Principal Medical Officer to the Niger Expedition under Colonel Lugard. His options were:

'1. Another billet from Colonial Office in a healthy climate. Such a billet as would be worth my while accepting would probably be a long time turning up.

2. Stay at home and try and get on Tropical School of Medicine- but pay poor.

3. Foreign Office said there was a possibility of post of physician to Legation at Peking falling vacant. Worth about £700 a year. Climate good. Drawbacks to this appointment not allowed private practice; so few members in Legation that one's medical knowledge would completely rust; and no further advancement. But an easy well paid billet. My prospects in Nigeria were good- whether it will be possible or politic to go back to Nigeria after say 2 years in Peking is a question that will probably present itself later.' (W.P. Diary, 6.6.1899 refers).

The Peking job did fall vacant, and, having been offered it by the Foreign Office, Wordsworth accepted it on the 22nd August.

Soon after, Lieutenant Francis Poole returned to England: 'I found him looking unwell. He must have had a terrible time in B.C.A. Yellowish, too fat below the belt, and unable to take much exercise.' (W.P. Diary refers). In November he went before a Medical Board, and was pronounced fit, before sitting his Captain's exams. He passed in all but one subject. Like his brother, he contemplated his future options:

'1. Exchange into another Regiment going to the Transvaal with the chance of getting Captaincy.

2. China, to learn Chinese as Officers are desired by War Office.

3. Return to Regiment in India.' (W.P. Diary refers).

On the 18th November, 1899, Dr. Wordsworth Poole left Charing Cross for Peking, arriving on the 30th December. The following day, as he settled in, a telegram arrived for him: "Poole, British Legation, Peking. Following from Lord Chamberlain: Queen Pleased appoint you Companion Michael George Services West Africa." As he wrote that night in his diary: 'Ain't it good biz at 32!' (W.P. Diary, 31.12.1899 refers). After two months settling in, making calls, and even having an Audience with the Emperor, March began with two bits of good news: 'Francis is coming out to China as they won't give him a chance in the Transvaal. He has already started learning the lingo and thinks he will be out here about the middle of May. The latest news also received is that Buller has relieved Ladysmith.' (W.P. Diary, 1.3.1900 refers).

The prospect of Francis's arrival particularly pleased Wordsworth- by May life in the Legation Quarter was proving a disappointment, with no prospect of any excitement in the offing: 'The desire for Africa comes over me fairly strongly at times. To be pent up within these 4 Legation walls looking after babies who get indigestion, and to be herded together in the city whilst there is the wind in the open and game in the thickets, fame and fever in fascinating Africa, is no life for a man.' (W.P. Diary, 14.5.1900 refers).

Arrival in Peking

Having Left England on the 31st March, and advanced to the supernumerary rank of Captain, Francis Poole arrived in Peking on the 20th May. He could not have picked a more in-opportune moment: 'Arrived at 2:45. Met by Wordsworth, take up my quarters in his house in H.B.M. Legation. Peking a city of the worst smells imaginable, and magnificent crumbling walls and gates. H.B.M. Legation a charming spot. All talk is about an anti-foreign society called Boxers who are strong in the Northern Provinces and have killed one of the C. of E. Missionaries. They are said to be moving towards Peking. A Meeting of Ministers was held today regarding guards for the Legation.' (Francis Poole's Diary, dated 20.5.1900, refers). 'Boxer scare increasing, interfering with the Legations moving to the hills... Boxers have got hold of Pao Tsing Fu and burnt railway stock there. I have received orders to organise a defence scheme for the Legation, count ammunition &c. 25 Europeans in all, about half a dozen who can shoot... Great scare, outlying mission stations very uneasy, Chinese insolent and throw stones at Foreigners- served out rifles and ammunition to the British student interpreters and Legation staff. All on guard, was up all night looking after things patrolling around Legation. Am in Military charge.' (F.P. Diary, 26-28.5.1900 refers).

Things were now getting distinctly uneasy, at a joint meeting of all the Legation Ministers on the 28th May it was decided to request that additional guards be sent from the various foreign fleets stationed on and off the Chinese coast. Many of the foreign community were worried that the guards would arrive too late, especially if the Boxers destroyed the railway, but on the 31st May the first contingents left Tientsin for Peking. The British contingent consisted of three Officers and 76 men of the Royal Marine Light Infantry, and three Royal Navy ratings. There should have been 100 Britons, but the Russians, unable to muster that number themselves, had objected to this pre-eminence at Tientsin railway station and forced the British to scale their contingent down. It was hardly an auspicious start. But their arrival in Peking was certainly a most welcome sight: 'Everybody went down to meet the guards late in the afternoon. French, American, Russian, Japanese, Italian, and British. Ours and the Americans were marines, the remainder bluejackets, in all about 300, ours naturally the smartest. What a sight Foreign troops marching through old Peking walls. Chinese thronging and looking on in awe.' (F.P. Diary, 31.5.1900 refers).

A period of calm now ensued, which was enough for Sir Claude MacDonald, the British Minister, to send a note to Admiral Seymour, the Commander of the Royal Navy's China Squadron, to say that the Legations would be the very last place to be attacked. However, the tranquillity was deceptive, and on the 6th June a Council of War was called: 'Conseil de Guerre, Captain Strouts in in command, Halliday and Wray his subordinates. Strouts and I talked over and Inter-Legation plan of defence with Officers of other guards. Americans and Russians to hold Legation Street south of canal and to fall back on us if pushed. French, German, Spanish, Japanese, Italians to fall back on French, but everyone to hold his own Legation as long as possible.' (F.P. Diary, 6.6.1900 refers). By the 13th June, the situation had become '...decidedly blue. Fires in all quarters of the city, mission compounds being burnt, shots fired down Legation Street. I take a Corporal and six Marines and rush off to the North Bridge where I prevent any Chinese coming into Legation quarters, and held up a troop of Imperial Cavalry. I think the row has begun. At midnight the Austrian picket opened fire with their machine gun at what they said were Boxers but they killed none, and after that the French, Russians, and Italian squibbed at shadows. We shall have a lot of trouble with these irresponsible, jumpy folk. I stayed on guard all night and was relieved by Wray on the bridge as the picket was strengthened. The Americans have sent a guard to the Methodist station. Everywhere Christians are being murdered by the Boxers.' (F.P. Diary, 13.6.1900 refers). The following day Poole was again on guard on the bridge all afternoon, and that evening at around 10:30pm a party of around 100 Boxers attacked his picket, but were successfully repulsed. On the 15th June he took over Captain Halliday's Picket ('A very responsible billet this'), as the latter, 'with Marines of all nationalities, went out to fetch in Christians under escort. At Nantung R.C. Mission they killed a lot of Boxers, who were massacring Christians and looting.' (F.P. Diary, 15.6.1900 refers). On the 17th June events took another turn for the worse, as the Chinese Imperial troops, with whom Britain and the other Powers were still officially at peace with, fired on Poole's Picket on the North Bridge for the first time: 'Alarm sounded on the North Bridge, and shots whizzed over our head, fired from the Imperial City. We sent a patrol out from the North Bridge and they were fired at and retired; our picket was strengthened and the firing continued for some time. I'm afraid we are in for it. We built a barricade near the Legation along the canal road and put our machine gun here.' (F.P. Diary, 17.6.1900 refers). Two days later Poole was at his usual post on the North Bridge when 'at midday 150 Chinese Imperial troops marched onto the Bridge and said they had come to protect us(?) You know the sort of protection that I mean, a horrible lot of scallywags. They are a few yards off us, and appear friendly, but we take it all with a grain of salt. In the afternoon an item of news reached me which caused my heart to stand still: we have received an ultimatum from the Chinese Government saying that within 24 hours all the diplomatic bodies from Peking will have to leave for Tientsin, and that escorts will be provided. I do trust that the Ministers will refuse to leave Peking and hold onto their Legations, as heaven help us looking after all these helpless women and children through a hostile country. I also suspect that were we to leave here, we would fall into a Chinese trap, and history would repeat itself with a repetition of Nana Sahib's massacre [at Cawnpore, during the Indian Mutiny]. So it's War with China.' (F.P. Diary, 19.6.1900 refers).

Siege of Legations

'After relieving Halliday on the Bridge, at 10:30am Strouts came and ordered me to withdraw my picket to the Legation- he says Baron von Ketteler, the German Minister, has been murdered by the Chinese, so all women and children of all nationalities are to come into our Legation and that the siege will begin. We built a barricade outside the main gate, and I returned to find women and children streaming in, with carts, coolies, and stores. I am turned out of my room and take up camp with my rifle by my side, quite like old times. Wordsworth gets ready his hospital. This does away with all thought of leaving Peking, so we must hold out till relief comes at all costs. At 4:00pm I heard firing from the north stables, the furthest advance post in my section of defence, and rushed there, and found four Chinese cavalrymen firing on us. These cavalrymen were reinforced by some dozen infantry who opened fire; also fire was opened from the Imperial wall and continued till dark. I had six marines with me and we returned fire when we could, the men behaved very coolly, very keen. Firing all night, sniping round the Mongol Market, fighting in the Austrian quarter. On duty all night, and so the siege begins.' (F.P. Diary, 20.6.1900 refers). For his gallantry on duty that day and night, Poole was Mentioned in Despatches (London Gazette 11.12.1900).

On the 22nd June an unsuccessful attempt was made to burn the British Legation at the south west corner. 'At 3:00 this afternoon the enemy set fire under heavy firing to a house on the south west corner near the stable. They were trying to set fire to our own Legation- the fire bell tolled, and the alarm sounded, confusion at first but then everyone turned to and knocked down houses and worked like devils under a deafening fire from the enemy, who were driven back.' (F.P. Diary 22.6.1900 refers). Fearing that they might try and burn the British Legation down from the Hanlin Academy to the north, Poole was again to the fore: 'With Strouts leave at dusk I got a party of 15 Marines, climbed over the wall by ladders, and lowered them the other side. The first European, I fancy, to ever enter the Hanlin was myself. We reconnoitred through the whole place right to the canal road, but found nobody. Returned, reported place clear to the chief, impossible to occupy at night, too few men.' (ibid). For the second time in three days, Poole would again be Mentioned for his services that night.

The following day Poole's premonition came true, as the enemy occupied the Hanlin Academy and set it on fire, in an effort to burn down the British Legation from the north: 'The enemy have set alight the buildings in the Hanlin, alarm sounded, I must take a party inside, clear out the enemy, and occupy the Hanlin. I asked Strouts leave to do this, got it, and got together a force of 10 British Marines, 5 American Marines, and 6 Volunteers; we make a breach in the Legation wall and stream quickly through, enemy fire volley, dash through door, enemy in big temple, fire and run, we pursue them, kill and wound several, there are about 250 Chinese Imperial troops in total, we hold the big temple, and drive the enemy out of the Hanlin. The famous Hanlin Library [the greatest library in the Middle Kingdom] is ablaze, we pull it down, get the fire under control, and place a picket in the Hanlin in front of the students' quarters. Nobody wounded. Hard work to get fire under control.' (F.P. Diary, 23.6.1900 refers).

The next day, the 24th June, was Poole's birthday: 'I am 30 today, dawn opens with brisk sniping all round and simultaneously.' (F.P. Diary, 24.6.1900 refers). The enemy made a fierce attack on the west wall of the British Legation, setting fire to the west gate of the south stable quarters, and taking cover in the buildings which adjoined the wall. The fire, which spread to part of the stables, and through which a galling fire was kept up by the enemy troops, was with difficulty extinguished; but as the presence of the enemy in the adjoining buildings was a grave danger to the Legation, Captain Strouts ordered them to be driven away: 'We made a sortie at the back of Cockburn's house and drove the enemy back. Captain Halliday severely wounded leading his men, one marine mortally wounded, another slightly.' (ibid). For his gallantry in leading the charge, and despite being dangerously wounded almost immediately, killing four out five of his assailants with his revolver, Halliday was awarded the Victoria Cross, the only V.C. given for the Defence of the Legations, and one of only two for the entire China War. Little did Poole realise at this stage that he was to be awarded the only D.S.O. given for the Defence.

Still the Siege continued. On the 28th June the enemy started a sustained fire against the British Legation from the Carriage Park. In a bid to force them back it was decided to try and set alight their barricade in the Carriage Park. Captain Poole was entrusted with the job. That night he made a hole in the Legation wall ready to get through at dawn the following day: 'At 3:00am on the 29th I fall in my party- a burning party of five, including myself, a left flank party of 3, and a right flank party of 3. The Burning party to creep up to the enemy barricade and set it alight, with the flank parties protecting the flanks. At touch of dawn we crept through the hole and with straw soaked in kerosene ran quickly along to the barricade and got within a few yards of it when the alarm inside the barricade was given and a heavy fire was poured into the burning party- no one fortunately hit. Barr [Poole's orderly] and I remained covering the retirement of the other three, who got safely across the zone of fire, next sent Barr, then I tossed off a round at the barricade and ran through the fire, which was coming from all quarters, wild but incessant. Got back to the main position, opened fire with some and withdrew the others through the hole in the wall, coming in last myself, having managed to get the entire party in without any being wounded thank God. Awful luck, but the venture failed, however, I think it will stop sniping.' (F.P. Diary, 29.6.1900 refers).

Throughout the first week in July Poole kept up his place in command of the Hanlin outposts. On the 5th July he was in command of a working part operating outside the Hanlin, chopping down trees in front of the main firing position outside the line of defence: 'The enemy opened fire on the working party. I ordered them in as I had misgivings, and I was looking after something else, when suddenly I heard a cry and rushed out in the direction outside our line of defence. David Oliphant [of H.B.M. Consular Service] was lying on his back wounded with a signalman [Leading Signalman Harry Swannell] alongside him kneeling. He had been foolishly cutting a tree, after I had given the order to retire- I knelt down beside him and could see he was badly hit. The enemy were dropping shot all round us, a couple of marines ran out and covered us, and we brought him in. Poor chap, he died after 3 hours. 24 years old, very promising man, clever, keen, active, it was his desire to make himself useful that brought him working into the Hanlin.' (F.P. Diary, 5.7.1900 refers). For his gallantry in tending to Oliphant, under heavy enemy fire, and on the strength of Poole's recommendation, Leading Signalman Swannell was awarded the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal, one of only two C.G.M.s to be given for the Defence of the Legations, and one of only 8 given for the entire China War.

On the 8th July Poole himself had a near miss: 'Bullet through my hat, wonder I don't get hit. We have made up a weird old-fashioned Chinese gun, found in a looted foundry, from which we fire Russian shells. Knocked down the barricade in the Carriage Park with it. Burnt Road Temple in Hanlin to clear our front, no one wounded. Very busy night and day, I have taken a pull and can get on without much sleep or rest, fortunately we get plenty to eat.' (F.P. Diary, 8.7.1900 refers).

The following day the Chinese changed their tactics- it was a New Moon, and to commemorate the event the enemy wished to slaughter as many Christian converts as they could. As a result, they concentrated their efforts on the Italian, French, Austrian, and German positions. Having assumed command of the International Volunteers, Poole inspected the various positions: 'Visited all the defences, so as to see how things are. French Legation, inadequate defence, in a very bad way, Chinese within 20 yards, Austrian Captain killed by a shell. French Legation must go, I'm afraid... Found Italians utterly demoralised from the loss of their comrades and the want of sleep and rest, with their main loopholes blocked up and cowering beside them, not daring to look or fire out of them. Cursed at them in bad French and scrappy Italian, got loopholes open and fired several shots out of them myself. Enemy's fire hot through the loopholes, only about 20 yards off, found one post completely deserted by the Italians, fortunately the enemy had not known this and I re-occupied it with 3 Marines and kept up as much fire as possible on the enemy. Strengthened all the Italian and French posts with our Marines and strengthened the defences and barricades, working all night. Built a gun platform and at dawn fired three shells into the enemy's barricade, drawing them back- a satisfactory night's work... Came back to find those thrice accursed Austrians and Italians had deserted their advanced post, because the enemy were firing into it. By dint of cursing and going oneself I got them back. Whenever firing goes on I have to rush around to see they haven't deserted their post.' (F.P. Diary, 10-11.7.1900 refers). Two days later, British marines were needed, for the first time, to reinforce every single post outside the British Legation.

On the 16th July, Captain Strouts was hit by enemy fire: 'Strouts mortally wounded by enemy fire. He never rallied, no reserve of strength to fall back on, worn out by nerve strain, responsibility, and want of sleep, as all the military men are. We buried him this afternoon- he was an excellent chap, his first active service, calm, self-confident, never hurried, always cheery, who was trusted by his men and did his work thoroughly and well- he is a great loss. He is succeeded in Command of the Marines by Wray, an excitable, irresponsible chap, who has not the confidence of his men... I am appointed Adjutant, and together with Squires, formerly a Lieutenant in the U.S. Army, and now the Staff Officer for the other Legations, run all the military arrangements of the Legations. (F.P. Diary, 16.7.1900 refers).

By now the siege had been going on for over a month, and with news that a relief force was on its way there was nothing else to do but wait. Apart from occasional sniping, and firing from behind brick barricades, the enemy seemed subdued, and the month ended on a good note, with Poole's diary entry reading very much like an end of term report: 'Our position is much stronger, and everybody is rested and more cheery, the weather is cool considering, patients in hospital bucking up, Wordsworth makes up list of casualties since 19th June, 60 killed, 81 wounded, very high 35p.c., this included Volunteers. Various rumours regarding advance of foreign troops. Take census of Volunteers under my charge, 87 of all nationalities, British, French, German, Belgian, Russian, Austrians, Italians &c. Of these, British excepted, the Russians have done their work the best. Of the Legation detachments, after our own, the troops are as follows:

Japanese: Have done the best work, and are superior to any other, possessing all the qualities that make up good fighting men, pluck, endurance, cheerfulness, obedience, and perseverance.

Austrians: Jumpy from the start, only too willing to leave a dangerous position.

Italians: Ditto.

French: Have held their position and have fought well, don't however understand adequate defences and have inferior discipline.

Germans: Splendid discipline, but have lost many men from not making barricades or adequate defences.

Americans: No discipline, older men than most, hysterical and often drunk on duty- they looted a drink store. Officers have no control over them. They have displayed dash on occasions, but are unsatisfactory people, as you never know what they will do. Very familiar and boastful.

Russians: Strong, stupid, and brutal on occasions, speak no known language so one can't say much to them.' (F.P. Diary, 30.7.1900 refers).

Peking Relieved

The siege dragged on for a further two weeks, during which the relief force was eagerly awaited: 'Inferior and insufficient food beginning to tell, dysentery too, next week will be a bad one. Troops may come any day now, in the Mpezeni Expedition [in North Western Rhodesia in 1898] we marched 400 miles in 15 days to relieve people who were not nearly so hard pressed as we are, only 80 miles to come and good roads- for myself it is unimportant, but women and children are suffering.' (F.P. Diary, 8.8.1900 refers). Finally, the enemy launched one last, desperate attack: 'Early morning, sharp firing all round. Heavy guns heard from the East. Troops expected. At 7:45pm a fierce attack on all sides, alarm sounded here, guns from Imperial Wall put six shells on our redoubt, silenced them with Colt automatic and rifle fire. Legation full of danger, up all night, fiercest attack I can remember but let them do their worst.' (F.P. Diary, 13.8.1900 refers). The following day was the day that those in the Legation had all been waiting for: 'At 1:30pm report from outside that Europeans were entering the Water Gate. Rushed out, saw four Sikhs running in under. We are relieved! Such a cheering, and remainder of force comes in at the Water Gate, guns are brought in and we shell the batteries on the Imperial Wall. Americans enter and occupy City Wall- hundreds of enemy killed by Maxims and rifle fire. Grand to see them tumble down. Russians arrive and French and Sikhs. Our guards relieved by the 7th Rajputs. We must occupy the Carriage Pak, relieving force too dead-beat, I occupy the Carriage Park with 65 Marines, clear out the enemy, hold it, and place picket.' (F.P. Diary, 14.8.1900 refers). But there was one person who was unable to enjoy the relief celebrations. During the course of the Siege Dr. Wordsworth Poole had treated 125 severely wounded men, one severely wounded women, and forty cases of sickness. It is testament to his skill and devotion that, in appalling conditions, in a 'hospital' with only 11 beds, whose patient population rarely fell below 60, and where food, antiseptics, and medicines were all scarce, the vast majority of his patients made a full recovery. Sadly though on the day itself he had been struck down with fever: 'In the afternoon I heard a cheer, got up from my bed, and hastily threw some clothes on. Saw Sikhs and Rajputs rushing into our Legation. 2 of the 1st Sikhs I had seen in B.C.A. We are relieved. Firing and cheers going on all round. Then with a temperature of 104 I went back to bed again.' (W.P. Diary, 14.8.1900 refers).

With Peking relieved, Poole was appointed A.D.C. to the Chief Minister. His first job was to try and stop all the looting that was taking place. Two weeks later, the Ministers all entered the Forbidden City, with much pomp and ceremony. Francis Poole was again on hand to record his views on the state of the various nations' forces, and the day in general:

'Russians: Impressive, Fine Men.

Japanese: Small, but business-like.

Germans: Very fine, steady marching, very stiff.

Americans: Fair.

Our own men: Sikhs and Rajputs especially, quite the most soldierly men.

Italians and Austrians: Bad.

French: Disgraceful.

Palace eunuchs then brought us tea and sweet meats. We entered all the rooms, a wonderful sight, the setting of magnificent buildings, the foreign devils marching over the stone bridges through the gardens with the golden lions and elephants of honour. The march round the Forbidden City is a sight a man can only see once.' (F.P. Diary, 28.8.1900 refers).

Poole recalls one final incident of the siege in his diary: 'During the early part our Union Jack on the central gate attracted much fire, and was dropping off the pole, the rope holding it being severed; the Armourer [T.S. Thomas] of H.M.S. Orlando, one of the detachment here, managed to lower the flagstaff somewhat and nail the Colours to the flagstaff, where they remained floating, contrary to the wishes of the American Missionaries, who were always complaining of their attracting fire; and so when we examined the staff and flag, there were 54 holes in the flag itself and 9 hits on the staff.' (F.P. Diary, 8.9.1900 refers). The battered flag, which flew throughout the Siege, is now at Windsor Castle.

Reprisals continued against the Boxers. In October 1900, Poole went with the expedition to Pao-Ting-Fu, in charge of the transport, and was subsequently appointed Railway Staff Officer, China, 11.12.1900, a position he held for the next seven months. On the 14th August, 1901, Poole received news that, for his gallantry and leadership during the Defence of the Legations, he had been awarded the Distinguished Service Order, to be back-dated to the 29th November, 1900. As his brother Wordsworth recalled in his Diary: 'Francis comes in for a D.S.O. It was expected so that the news was not a surprise, but he will be glad to have got recognition after many toilsome jobs that seemed to bring nothing.' (W.P. Diary, 14.8.1901 refers). On the 15th November 1901 he was presented with his D.S.O., the only one given for the Defence, by the Officer Commanding Troops, Peking, at a parade of the Garrison, fittingly held on the Carriage Park, the scene of some of his most daring exploits, and overlooked by the British Legation.

The year though was to end on a sad note. On the 11th December 1901 Dr. Wordsworth Poole contracted typhoid. Francis Poole was with him during his final days, but to no avail, and his brother died on the 9th January 1902.

Travels in Africa and Asia

In January 1903, Captain Poole took up an appointment with the Egyptian Army, and served with them during operations in Bahr-el-Ghazai, Sudan, 1903-04, before being posted to the Intelligence Department, Egyptian Army, 1906. In this role he was free to travel extensively around North Africa and the Middle East, and over the next two years sent back much valuable Intelligence Material, particularly on the state of the various countries' military capabilities. In 1908 he served with the 15th Sudanese as Senior Inspector and Acting Governor, Halfa and Berber Provinces, Sudan, for which service he was awarded the Order of Osmanieh by the Egyptian Authorities.

With the Abor Expeditionary Force

In February 1910 Captain Poole finished his secondment to the Egyptian Army, and embarked upon further travels, this time to North and South America, Korea, Japan, Manchuria, Mongolia, Siberia, and India. In March 1911, news was received that a British party had been treacherously murdered by Abor tribesmen. Such wanton savagery could not be allowed, and the Indian Government decided on the despatch of a punitive expedition to Aborland. Poole, who by now had arrived in the area, was permitted to join the expedition: 'On the 20th October 1911 the first column, some 500 rifles of the 2nd Gurkhas, started off. Little was known about the country in front of us. Owing to the difficulties of transport no tents were carried with the force, and the chronicle of the next three weeks with the main column, in what is probably the rainiest part of the world, is but a dreary one, telling the tale, as it does, of constant jungle-clearing, road making, of brushes with elusive Abors, of attempted ambushes, of rock-shutes discharged, of fatal casualties from poisoned arrows, of rain-sodden bivouacs, of fever and water-logged camps. Of the pomp and circumstance of glorious war there is little, only a bedraggled slender force moving step by step in a country whose difficulties seemed to increase every day. The foothills were succeeded by steeper hills heavily forested; no clearing existed unless there was cultivation. On the 19th November the striking force, with the minimum of baggage, reached a razor-backed rock, the ascent to which was a very severe one, from the bed of a mountain stream. Without doubt this ground was dedicated by the Abors to the God of Battles... A stockade was soon discovered, from which a shot rang out. Simultaneously an enormous rock-shute was discharged and thundered down the gorge. Fire was immediately opened at the stockade, from which showers of arrows were coming. With the rattle of musketry were blended the crash of six more rock-shutes, discharged from the stockade one after another, and the defiant shouts of the Abors.

The ingenuity displayed by the Abors in defence of this stockade recalled the shifts and contrivances used by the Boxers and Imperial troops in China during the troubles of 1900. Lieutenant Buckland first entered the stockade, followed by the remainder of his party, who encountered the Abors in flight, six of whom were killed. One was in close grips with a Gurkha officer when Lieutenant Kennedy shot him with his revolver. With the flight of the Abors the stockade was taken. The topmost bastion of the stockade was picketed just before nightfall, and the heights around them crowned- we had been twelve hours continuously under arms. On the 4th December the Abor stronghold of Kekar Monying was captured, and with the capture of the village of Kebang four days later, the back of the Abor resistance was broken, and the prestige of the hitherto unconquered Kebang clan received a severe blow. There were small affairs of ambuscades on the part of the Abors, but any concerted opposition was at an end. By April 1912 all exploration parties had come in, and the withdrawal of the force began.' (With the Abor Expeditionary Force, Captain Poole's account of the Expedition, written under the pseudonym 'Wanderer' refers).

The Great War

On the 18th December 1912, Poole transferred to the Middlesex Regiment with the rank of Major, and went with the 3rd Battalion to France, 14.1.1915. Invalided home in February 1915, he was appointed a Brigade-Major, 8th Reserve Infantry Brigade, New Armies, March 1916, before re-joining his old Battalion in July 1917. After a period in Italy, as a General Staff Officer, November 1917 to March 1918, he was appointed to the Command of the 23rd Battalion, Middlesex Regiment, on the Somme, 2.3.1918. After the Armistice he held more Staff Appointments, was Mentioned in Despatches (London Gazette 5.7.1919) and created an Officer of the Order of the British Empire.

In 1919 Poole re-joined the 1st Battalion, Middlesex Regiment, as Second-in-Command, but was invalided out the following year, and after a brief period commanding the 17th London Defence Regiment, finally retired from the Army on account of ill-health with the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel, 20.7.1921. In 1925 he was appointed Commandant of the Surrey Cadet Brigade, and served in the post until 1943. During the Second World War, by now aged over 70, he travelled all over England helping to raise new Cadet Units as part of the War effort.

Lieutenant-Colonel Francis Poole died at home at Farnham, Surrey, in November 1950. Few men can have crammed so much experience into 80 years of life.

The Peking Siege Commemoration Medals were struck at the instigation of Mr Arthur D. Brent, an employee of the Hong Kong & Shanghai Bank, who was himself present throughout the siege, and were presented to those who were present at the Defence of Legations, 20th June to 14th August 1900. The inscription on the reverse represents those words that appeared on the wall at Belshazzar's Feast, and were interpreted to mean 'thou art weighed in the balances, and art found wanting' (Daniel, Ch.5, v.26-27).

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£85,000