Auction: 24001 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 142

Sold by Order of a Direct Descendant

'His religion was displayed in everything; it was the ground-work, I believe, in fact, the principle of his life.

In the Spring of 1857, when the troublous times were only in the distance, and the idea of such a storm as we went through was scouted by the majority, he went to Cashmere. But ere long the mutterings of the thunder became louder and louder, and orders were sent to him to rejoin.

In an incredibly short time, I cannot say in how many days, he arrived. In fact, as we marched out of Sealkote, a figure presented itself to us, nearly black with dust, and footsore, walking in. The bearers of his doolie had become exhausted, and he had trudged many miles on foot. The next day he joined us, ready for the campaign.

In everything, whether his duty to his God or to man, to do his best, and that with all his strength, was his text. He was wounded (at Trimmoo Ghat) by a musket ball through the foot, and though I begged of him to go to the rear, he would not leave me, but fought his gun, wounded as he was, through the action, and rode home eight miles on a gun horse, to supply the place of a Driver who was killed.

During the several actions at Bolund-shuhur and Agra, he displayed his usual coolness.

During the Relief of Lucknow we were together nearly the whole of the time in a most dangerous position. A gun was playing on us from a distance of about 25 yards. He was sent to silence it, which he did, and the work required all his coolness. He masked our gun by putting the muzzle through a hole in the wall their round shot had made. The first round brought down the whole wall and left us exposed. Round after round was exchanged, until the enemy's gun gave in.

On that afternoon we stormed a thatched Hospital and a Mosque, from which the enemy kept up a constant fire. They were taken, but the Hospital was fired, and we had to retreat. A poor Drummer, wounded, was left for hours behind a wall in a garden. A hot fire was kept up on the garden.

Harington with two others rushed out and brought in the wounded man. For this he was recommended for the Victoria Cross, but got it from the universal vote of his brother officers, to whom was given the pleasing task of electing the bravest of the number.

Harington deserved two Crosses.'

Major-General Sir George Bourchier on Captain Harington.

The outstanding 'Clause 13' V.C. Pair awarded to Captain H. E. Harington, Bengal Artillery, for gallantry during the Relief of Lucknow in November 1857; Harington was thrice wounded in action during the Indian Mutiny - twice presumed killed in action - and played an important role in the entire campaign

He was confirmed as having won the V.C. for gallantry in the Relief of Lucknow, but was denied the honour as it had been understood he had been killed - at a time when the ultimate reward for gallantry could not be awarded Posthumously; it was no surprise he was unanimously voted by his brother Officers to eventually receive the honour in place of 'the one promised by Sir Colin [Campbell]' - his comrades knew he had truly won the reward several times over

Having taken a bullet through the foot, head and back during his career, he was overcome by cholera at Agra in July 1861 at the tender age of just 29

Victoria Cross, the reverse of the suspension bar named 'Lieut. H. E. Harington. Bengal Artillery', the reverse centre of the Cross dated '14 to 22 Novr. 1857’; Indian Mutiny 1857-59, 3 clasps, Delhi, Relief of Lucknow, Lucknow (Lieut. H. E. Harington, Bengal Arty.), correction to the surname - to ensure just one 'r' - otherwise good very fine (2)

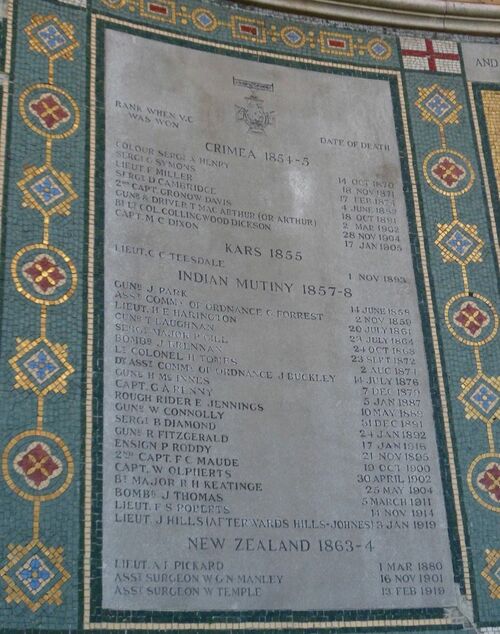

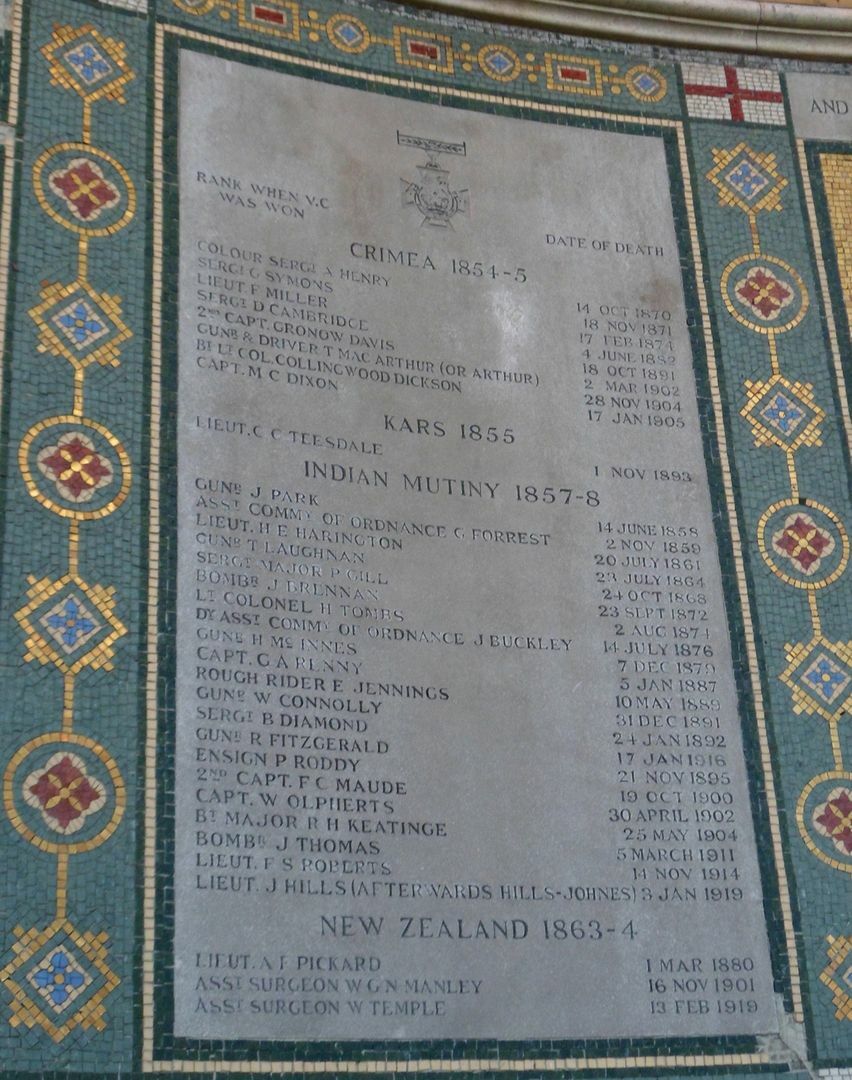

V.C. London Gazette 24 December 1858 along with Rough Rider Jennings, Gunners Park, Laughnan & McInnes, all members of the Bengal Artillery, Harington the only Officer being duly rewarded:

‘...elected respectively, under the 13th Clause of the Royal Warrant of the 29th January 1856, by the officers and non-commissioned officers generally, and by the private soldiers of each troop or battery, for conspicuous gallantry at the relief of Lucknow, from 14th to the 22nd November 1857.’

Victoria Cross Royal Warrant - Clause 13 Awards

When drawing up the original warrant for the Victoria Cross there was understandable concern with singling out one or two individuals for special recognition for acts of bravery as this had the potential to cause resentment amongst their comrades, as was recognised by Lord Panmure and Queen Victoria herself:

‘The Queen feels that the selection will be dreadfully difficult, and possibly may give more heart-burnings than satisfaction.’

This probably explains why so many medals were given to those men that had saved the lives of others, rather than trying to compare the daring or danger of one particular act over another, which was almost certainly going to lead to all manner of claims and disputes. On the other hand, few would complain at the Victoria Cross being given to those who had risked their lives saving some of their own comrades and this is especially true in circumstances where the advice of Prince Albert’s memorandum of 22 January 1855 was followed. He suggested that:

‘...their distribution should be left to a jury of the same rank as the person to be rewarded. By this means alone can you ensure the perfect fairness of distribution and save the officers in command from the invidious task of making a selection from those under their orders’.

The announcement of the creation of the Victoria Cross appeared in the London Gazette of 5 February 1856, with Prince Albert’s suggestion being incorporated into Clause 13 as follows:

‘Thirteenthly: It is ordained that, in the event of a gallant or daring act having been performed by a squadron, ship’s company, a detached body of seamen and marines, not under fifty in number, or by a brigade, regiment, troop or company, in which the Admiral, General, or other commanding such forces, may deem that all are equally brave and distinguished and that no special selection can be made by them: then in such case, the Admiral, General, or other officer commanding, may direct, that for any such body of seamen or marines, or for every troop or company of soldiers, one officer shall be selected by the officers engaged for the Decoration; and in like manner one petty officer or non commissioned officer shall be selected by the petty officers and non commissioned officers engaged; and two seamen or private soldiers, or marines shall be selected by the seaman, or private soldiers or marines, engaged respectively, for the Decoration; and the names of those selected shall be transmitted by the senior officer in command of the naval force, brigade, regiment, troop, or company, to the Admiral or General Officer Commanding, who shall in due manner confer the Decoration as if the acts were done under his own eye.’

A total of 29 Victoria Crosses were awarded under Clause 13 during the Indian Mutiny 1857-59, of which at least 16 are known to reside in Museums, with one other recorded as having been lost by the recipient.

Of the 5 awards to the Bengal Artillery, 2 (Gunners Laughnan & Jennings) are known to exist in Museum collections.

The Victoria Cross was not awarded again under Clause 13 until the Boer War, when 4 were given to members of Q Battery for the action at Sanna’s Post, all of which are known to be in museums. The remaining 13 balloted awards were all given for gallantry during the Great War (6 for the Lancashire Fusiliers at Gallipoli; 3 to ‘Q’ Ships; and 4 for the Zeebrugge raid), 12 of which are known to be in museums.

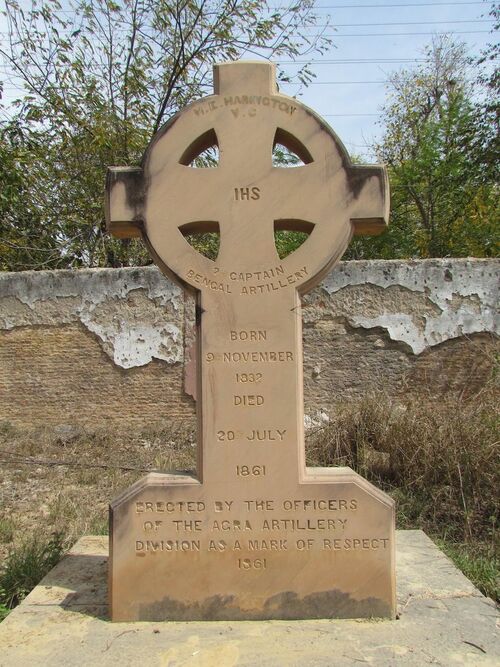

Hastings Edward Harington was born on 9 November 1832, son of The Rev. John Harington. Educated at home by his father, thence at Reading School and the Military College, Addiscombe, young Harington was commissioned into the Bengal Artillery on 12 June 1852. Whilst at Addiscombe, Harington was regularly reported as having been 'Exemplary', taking 3rd Place for the Artillery, coming 1st Place in Latin and 2nd Place in Hindustani amongst the prizes. Besides that, he was noted by his classmates, one of whom latterly wrote:

'The very look of the man told you he was upright, in the Bible sense of the word; I was with him at Addiscombe, and even there he kept himself undefiled. I wish all Christians were like him - he was on a grand and noble scale. He did not mention his name till I asked for it. 'Hastings Harington,' he said. 'Ah,' he added, 'I saw his father once at the Paddington Station. I and some other young fellows were talking about Addiscombe, and he came and asked us if we knew his son. I was glad to see the father of such a son.'

He left England in September 1852 and was thrown into the life of a Regimental Officer in India, mainly serving at Peshawar and Sialkot. A comrade at this time wrote of his devout nature:

'I never met in this country [India] a more thoroughly high principled and well disciplined young man. He is not ashamed of the gospel of Christ, and by his diligent and devout observance of all holy ordinances he is an example to many, and we delight to welcome him to a little meeting held every Wednesday evening for prayer and reading the Scriptures...He seems very studious and determined to avoid debt, to which end, in the Artillery, he must use considerable self-denial. Yet he puts by something for God's work, and brings something monthly, for the Peshawur Mission.'

Taking his first march up-country from Dum-Dum to the Punjab, Harington wrote home regarding their having halted at Delhi. It was, however, a Sunday and thus he would not break the Sabbath to explore. He mused that some day he might like to explore the city about which so much was written. That opportunity would certainly present itself in a few short years, under very different circumstances.

To set the scene of the unit that he joined, it is perhaps best to quote one who served in them, in this event a young Second Lieutenant Roberts, who joined the unit in December 1851 (later Field Marshal Frederick Sleigh Roberts, 1st Earl Roberts, V.C., K.G., K.P., G.C.B., O.M., G.C.S.I., G.C.I.E., V.D.):

'From Cawnpore I went to Meerut, and there came across, for the first time, the far-famed Bengal Horse Artillery, and made the acquaintance of a set of officers who more than realized my expectations regarding the wearers of the much-coveted jacket, association with whom created in me a fixed resolve to leave no stone unturned in the endeavour to become a horse gunner. Like the Cavalry and Infantry of the East India Company's service, the Artillery suffered somewhat from the employment of many of its best officers on the staff and in civil appointments; the officers selected were not seconded or replaced in their regiments. This was the case in a less degree, no doubt, in the Horse Artillery than in the other branches, for its esprit was great, and officers were proud to belong to this corps d'élite. It certainly was a splendid service; the men were the pick of those recruited by the East India Company, they were of magnificent physique, and their uniform was singularly handsome. The jacket was much the same as that now worn by the Royal Horse Artillery, but instead of the busby they had a brass helmet covered in front with leopard skin, surmounted by a long red plume which drooped over the back like that of a French Cuirassier. This, with white buckskin breeches and long boots, completed a uniform which was one of the most picturesque and effective I have ever seen on a parade-ground.'

So it came that by 1857, Harington had been promoted Lieutenant but by that point had not taken any leave. His health began to flag and as a result by General Order in April 1857, he was granted 60 days leave. So it came that on 1 May 1857, he began a journey to see Kasmir.

Mutiny - opening shots

Reaching Sirinagar on 16 May, he went out to explore the city on Monday 18 May, but wrote him in some distress on 19 May:

'My visit to Cashmere has been suddenly brought to a close. This morning, hearing that Major W. had come, I went down to see him. He said that an order was out for every officer not on sick leave to rejoin his Regiment. I am quite in the dark as to news, and only hear reports, but it seems a mutinous and disaffected spirit is spreading fearfully among out native troops, and the European Regiments are all that can be depended on.

I have to rejoin Bourchier's Battery as soon as possible, and set out on my return tomorrow. I fear the difficulties I encountered before are little likely to be lessened during the short time, but I must take the shortest route.

My tatt has not yet arrived, so I must go on foot, with one or two men and a coolie to carry a little bedding; and the rest of my traps I shall leave to follow by the longer Pooneh route. I mean, the Lord willing, to go double marches through Rajawir to Bhimber, which is in the plains; and I have written to Dawes to lay a doolie dak from there to Sealkote for me. I can't take anything more than what I have on my back, and I shall have a little hardship and exposure. But I half expected this when I left Sealkote, and my case is not so bad as that of those who looked forward to a comfortable six months' leave.

It is a time of much distraction and everything to unsettle me. I know not what is before me; but Christ does, and that is enough. I am very thankful to have had this recreation and holiday; but still I am always half taking my daily blessings and mercies, as matters of course. It is sweet to pray for each other. Dear old Rutherford says, 'In making an errand to the Throne of Grace for others, we seldom fail to bring away something for ourselves.'

In the coming days it was a slog to say the least. He reached Gujaranwala by 29 May, walking in excess of thirty miles a day numerous times and crossing the passes at Pur Pinjab, Ruttum Pir. By Sunday 24 May 1857, his boots were totally worn out and his feet not able to take any more, needing to hire poines to make Bhimber. Finally reaching their former HQ, he found the place totally deserted. He continues:

'Presently a tremendous dust-storm came on, which forced me to lie out in the garden for an hour, with my head under a pillow, and nearly smothered with dust and small stones. In this horrid plight I dropped asleep, now and then waking to the consciousness that the storm was still going on and that I must stay where I was; and meanwhile having fitful dreams and nightmares of losing my way among ravines and torrents. A little before two the storm abated sufficiently to let me stand up, and having collected the terrified doolie-bearers, I groped my way ahead of them, helped by gleams of lightning to our mess-house: we routed up the mess-bearer, and thankful at last to have a substantial roof over my head, I threw my begrimed and wearied self on the floor, and slept soundly till morning. The station seemed all deserted, and I was making a hurried attempt at a kind of wash in the verandah, when G. came by, and I found that two of Dawes' guns and 200 men of the 52nd had been left, and, that I might find my camel-trunks and clothes in the Magazine, where everybody had been collecting their superfluous property ere leaving.

I hobbled down there, got out my sword, pistol, and a shirt or two, but hunted in vain for a particular chest, which had my boots and shoes, and some necessaries, which I had put by for an emergency. I then found my way over to Dr. M.'s, who I heard was going out to join the column in the course of the day, and got the promise of a lift in his buggy. We got out to Camp in time for dinner, and found Bourchier had brought on my horse and tent, but both had gone on to Wuzeerabad. We all got some hours' sleep, and at eleven at night marched again. I fell into my old place in the Battery in a nondescript kind of costume of odds and ends, which was anything but uniform, and mounted on a spare Battery horse, already loaded with no end of harness and gear. We reached Wuzeerabad early next. A column has been rapidly formed and put under command of the best man that could be picked out, Neville Chamberlain, who has the temporary rank of Brigadier-General.

We are in the middle of the hot weather, and the heat in the tents is fearful, varying between 100° and 120°; but we are all, thank God, in good spirits, and ready for anything. I am writing in Dawes's tent. He is so kind to me, and a splendid fellow to be in service with. I have hardly anything with me, and have borrowed pencil and paper; the ink is dried up. It is hard amid all this wear and tear of strength, little sleep at night, and broiling, walking days, to read or pray, or do anything, yet I feel I am 'kept.''

Delhi - street fighter

Some weeks after, their Column then had General Nicholson at its head, attempted to march forth into order to head off the rebels on the way to Delhi. Thrown into the action at Trimmoo Ghat, Harington was wounded for the first time, taking a bullet through the foot. He continues:

'When the smoke of our first round or two had cleared away, we found some of their cavalry among our guns. One of them, as he passed me, hit me over the back, but his sword turned as he did it, and it did no harm, and Bourchier shot him just behind me with his revolver." His horse being shot in the chest, " I took my place," he says, "in the team, on a horse that was wounded in the legs"'

He was not to be put down by the wound:

'There is hardly any inflammation, which the doctors say is owing to my extremely temperate habits." [He drank only water. " I can manage splendidly with a crutch, and I think I can manage to ride well enough, if need be, without using my leg. You will with me praise our Heavenly Father that I am safe and well. It is a sweet thought, 'preserved in Christ Jesus,' and safe in Him, despite all shortcomings and infirmities, and unfaith- fulness to Him and one's best interests. I hear a report that 150 men have returned for plunder, and that there is a chance of four guns going after them. I shall go, if we can get leave. We are so short of hands, it is every thing for the men to have their own officers with them, if possible. I write this scrawl on my back, and it is nearly dark.'

Harington was next into the action during the Siege & Assault of Delhi, when he displayed the types of gallantry that made him so famed:

'I had to take a howitzer and gun through narrow winding lanes, &c., to reach and take the Gate.

Bodies of men and animals were lying about, terrifying my two teams (I left the two waggons here), and my own horse, in his fright, backed in among the wheels, got entangled, and was thrown down and injured, so that I was obliged to stay on foot the rest of the time.'

Harington saw the peril his howitzer troop were in and gave the order, with the few men who remained present, to unlimber the gun. They got it into action, blew open a high closed gate which shut the street, the whole time in a hail of rifle fire. The enemy then came up and poured in grape:

'Once more there were cries of 'Run the guns forward!' and five men and myself did so; and again and again my howitzer fired. Another round of the rebels' grape struck down the port fireman on my left, grazing my left side slightly, and two more of my men were wounded. I fired the gun myself, and we managed to serve it," (standing thus alone in the forefront), "till the word was reluctantly given to retire. Though sad, the sense, if not the actual words, kept me content, 'Be not dismayed, for I am thy God.''

This was the first action when those present put him forward, stating '...Lieutenant H. deserved the V.C. for his conduct on that trying occasion.'

After Delhi was won on 21 September 1857, Harington proceeded with Greathed's Moveable Column up to Agra, via a 44-mile forced march on 10 October. Setting up to rest and bivouac, they were sprung upon by several thousand, whom they took to action and drove them towards a stream some 9 miles off:

'It was only God's good providence that turned our surprise into a victory, or, at least, a success. When I got back into camp, I found that a round shot had gone through the side of our little mess-tent, and that two camp-followers had been killed close by mine. Charlie Hunter's grass- cutter had been killed, and his bearer wounded...

It put the mettle of our horses to a pretty severe test, and proved that notwithstanding the heavier calibre of our guns, and the smaller size of our teams, they can at a pinch ably do the work of Horse Artillery. In one place where we could hardly see each other for the high 'jo- ár' crops, the Battery seemed to have bid goodbye to all discipline, and we rushed along at a mad gallop, men and drivers shouting till hoarseness made the hurrah a shriek.

We soon past the rebel camp, and by-and-bye got on to the Gwalior road, which was strewed with Hackeries, and found that they were in full retreat towards Dolpore.

Our Battery pulled up while the cavalry and Horse Artillery went on in pursuit, and after a short breathing time we again set out in the same direction, and after a good swinging trot of some miles came to the Khàri-Naddi, where our force had halted, having driven the enemy across with loss. Guns of various sorts, to the number of 12 or 13, fell into our hands, three of them being immense brass ones of great value, (that is, the metal itself, not as ordnance), and two of these were found at the old tomb which had been bothering us at first.

We were all cruelly tired and thirsty, having calculated on a day's rest after our previous nights' forced marches, and made no sort of arrangements for provender, but even the hour's bare repose by the river was delightfully welcome. After we had watered our horses and given them all the relief we could after the severe grinding they had had along the Puckka road, we put to' again as the sun began to get low, and the column slowly crept back again towards Agra. Oh, how long and weary did those eight or nine miles seem to us poor jaded fellows, who had come in from Hattrass, or rather Bijeghur, though we had quickly rattled over them a few hours before. Here and there lay a Palki,, or dead camel, or burning Hackery, or wounded bullock; the intervals being filled up by heaps of plunder and ammunition and rubbish, which had been well turned over and searched by probably every straggler who had dropped in rear during the pursuit.'

Lucknow - V.C. - second wound

The Column crossed the Ganges on 30 October and by 12 November was a part of Sir Colin Campbell's Force, assembled to execute the Relief of Lucknow. Since those legendary events in November 1857, historians have spilled an ocean of ink to cover the individual actions. A letter from Harington, written in April 1858, takes us to the action and tells more on the facts surrounding his having earned his V.C.:

'On the 18th of November, B[ourchier] and I, with two guns of our Battery, went on picquet into one of four compounds which had been selected as desirable points to be held on the left of our position, running from Secundra Bagh. Percy's uncle, Col. Biddulph, had the arrangements there, and Brigadier Russell (84th) commanded the post, which was a hot one, and an important one. Some Companies of the 23rd Fusiliers (young Anstruther's Corps), and 82nd Foot, were also with us, and afterwards a Company of Royal Artillery, with light mortars, joined us, and some Madras Sappers. The hospital, and all to the front outside these houses, and their compounds, was the enemy's, and from their loop-holes, in the different buildings beyond, they could see down into us, and kept up an almost incessant musketry fire.

They also had a gun in position, but I only saw it fire once, and then mine shut it up - but the shot came through the compound wall just by me, and wounded Brigadier R., knocking over, but not injuring, Bourchier at the same time. Just then, one of my gun's crew put his eye for a moment to one of our loop-holes, and got a bullet in his cheek, of which he died very soon.

We had entered these compounds by holes in the wall, from some lanes behind. In the afternoon, an attack was planned on the hospital, which was almost close by, at the corner where the road from Dilkusha House met the other. Both roads were enfiladed by the Sepoys' musketry fire.

Poor Colonel Biddulph happened, for a second to peep out into the road from the gate, and got a ball in his head, and died without a groan. My second gun, a howitzer, was in the gateway of our compound, pointing towards the hospital, and in conjunction with the attack, which was an Infantry one. We had been firing grape and shell as long as we could do so without hurting our own men.

Some doolies had to go with them, in case of accident, and they went out of our gate; but the dooliebearers got so frightened, that they dropped two of the doolies in the road, instead of carrying them across into the orchard; and tried to get under cover from the musketry fire; some hiding in the orchard, and, I think, one or two hid in the doolies themselves.

After the attack had failed, B[ourchier] and I, and our men, were standing with one gun at the gate, and the doolies being still outside, and no one seeming to think of the poor bearers, I volunteered to bring them in, but B. distinctly forbade my doing so. Just then, Lieutenant Hackett, 23rd Fusiliers, came up, and said something about there being a wounded European somewhere out in front. I said, ' Who's coming with me?' and Gunners Ford and Williams volunteered, and we three went with Hackett across the road, over a little ditch, and a strip of open ground, and a small wall, into the orchard, and found the wounded man, and with him a noble little band- boy, George Mouguer, of the 23rd. He had, I think, been sent at first to accompany the doolies, and help the men, and when every one else had retired, he must have found the wounded corporal, and, refusing to leave him, had staid by him under the trees, till we found him.

We got in the wounded man all right, none of us being touched, and put him into the house where poor Colonel Biddulph, Brigadier Russell, and some others lay.

I was at once told that the names of us five had gone up for the V.C., and felt pleased and thankful that God had strengthened me to do my duty. But I could hardly do more than hold my tongue, and leave the matter to others.

On the 20th, I was myself wounded in the same compound, and was conscious of little more, till I found myself in Dilkusha House, on the 21st. From that time to this, I have had sundry congratulations on having received the V.C., and, on the other hand, hearing now and then that there was a hitch somewhere.

Meanwhile Sir Colin published a G.O., saying that, in consequence of the distinguished conduct, &c., &c., under his own personal observation, of the 1st Troop, 1st Brig. , B.H.A., 2nd Troop, 3rd Brig. B.H.A., and 3rd Company, 1st Batt. F.A., throughout the operations at the Relief of Lucknow, five V.C.'s would be given. One to one officer, and one to one non-commissioned officer from among the two Troops and Companies, and one to one gunner from each of the above; the officer to be selected by the votes of the officers, the non-commissioned officer by those of the non-commissioned officers, and the three gunners by those of the gunners of these two Troops and one Company. It now turns out, that though I have lost the V.C. for bringing in the wounded man, in consequence of some little informality in the wording of the report, the kind votes of my brother officers have bestowed upon me the one promised by Sir Colin. It is hard to analyse my feelings - I am not insensible to the honour, but I am thankful to feel each day, more and more, that earthly and worldly distinctions cannot, alone, give peace of mind, or give rest to the soul.

Dear McMahon, in a beautiful letter, appropriately refers me to Gal. i . 24, and, to my own mind, Gal. vi. 14, has come with much force, two or three times. Pray for me to lay this, and all else I am, and have, continually at Jesus' feet.'

He made little reference to the severe wound which had struck him down. By all accounts it was considered to be a mortal wound, with the official word being given to his men that Harington had expired. This is also the likely reason that his name was struck from the list of V.C.'s to be bestowed under the orders of Sir Colin Campbell.

Details of the wound mean it was no surprise he was thought killed outright, with a bullet entering his head under the right ear. Having entered the skull, it 'smashed', leaving him deaf in the ear, with lockjaw and rendered unconscious. A brother officer wrote:

'He is most patient under it all, and finds a consolation in the sources to which, whether well or ill, he has always looked. You may fancy how my heart throbbed when I heard it said that he has a good chance of being recommended for the V.C. for distinguished gallantry in bringing in, with one or two others, a wounded man, under a murderous fire. Get the Cross or not, he has done what deserves it, and that is everything.'

Another wrote to his own friends:

'Harington (though at one time his life was despaired of) is now almost well. He is much valued as an officer, and acknowledged to be a first-rate one. He is patient, energetic, and intelligent, and at the same time cool and brave; but men actuated by the principles that he is, must ever have a quiet mind. He has been recommended for the V.C.'

Harington's life still hung by a tread and he was immobile, carried with the force back to Cawnpore. His recovery was nothing short of a miracle and he was regularly chided by his comrades for still only choosing to drink water '...I will stick with my beverage, and can work on it well, and can afford to smile at all injunctions to take beer.'

Somehow returned to the active list, he joined the Horse Artillery and provides us with a first-hand account of those days:

'All at once a naval officer came doubling up towards us, very much out of breath, and we could make out that he was shouting out for a doolie. Then he said, 'that an officer was shot,' and then, worst of all, it turned out that splendid fellow, Sir William Peel himself had been just hit by a musket ball in his thigh. The sailors were evidently enraged that their gallant captain, of all others, should have been hit; and forthwith sent a savage 68-pound shot, apparently exactly to where the puff of smoke came out just before. I felt at first as disgusted and angry as they were, but was soon content with the recollection that some one had lately told me that Captain Peel was a pious man, so that the wound, even if deadly, could not harm him; and it also seemed that God would take away the men we seemed to want most, to make us lean more on Him. I am rejoiced since to hear that the bullet has been extracted, and that the wound is going on favourably.

At one o'clock, the 42nd and 93rd Highlanders, and 4th Punjab Rifles began forming up, and the 63rd were in reserve; and almost immediately our troop moved down with them into the hollow between us and the Martinière. The sailors kept up their fire from above, and I, with three guns, filed along the walls of the Martiniere compound quickly, till near the water's edge. We then opened a rapid fire on the building and ground, right and left, to cover the infantry. It was a pretty sight to see them dash over the ground with a cheer, and in a few minutes all the Martinière premises were ours.

The fellows didn't make any stand, but bolted back, over the canal as hard as they could, and a great part of that formidable line of earthwork, which they have been hard at work upon for the last three months, fell into our hands almost without a struggle, and we had very few killed or wounded. Our troop was ordered to bivouac where it was, in the Martinière grounds, for the night, but before dawn next morning, General Lugard came to order two guns off sharp to the other side of the canal, to support the 42nd Punjab Rifles up there.

Quite early yesterday morning (11th) some staff - officer came dashing up to say that the 53rd had got as far round to the right asthe Secundra Bagh, but were hard pressed, and I was to be off there sharp in support. I went, picking up a covering party from the 90th in the way, and found matters by no means so bad as I fancied. I went with the commanding-officer to the top of one of the turrets, and thence looked out on the well-known and hard-fought ground. The enemy's second line of defence came in front of us, from the Shah Nujjeef, past the Motee Mahal and Mess-house, away down towards the Tara Kothi and Barracks and there was a good deal of interchange of musketry between them (from behind covers), and our fellows. As the Colonel commanding the post was uneasy, we got one of my guns (a howitzer) into position, and gave them a few shells, and then the firing gradually stopped. In the afternoon, they opened fire from two or three guns, out of embrasures which we had thought were unoccupied, and I was sent out alone, about 100 yards to the front, to try and silence them-the Infantry looking on from the top of the towers, &c. The first two or three rounds from my two guns brought down on me a crossfire from some embrasures to the left, as well as those in front, and from the hot position I was in, I did not expect to come out so well. Fortunately, the left guns were some-what sunken, so that they struck the ground and bounded over me, but the shots from the guns in front were fear-fully close, and in capital direction.

One went over my head as I was laying the howitzer, and went right into one of the best pole horses, killing him on the spot, but, thank God, none of my men were touched. It seems so odd my being in tent once more, and eating breakfast like a gentleman, at a table, &c., after being five days away on picquet and other duties. I've got to go to stable-duty, so I will close for the present. My poor horses were 48 hours traced to the guns, without being able to lie down, before they could be changed, so it is high time I should go and see them rubbed down...

On Sunday Morning (14th) I was off again to the Secundra Bagh, in charge of two guns of our troop. I reported myself to a Colonel Ingram, of the 97th Foot, who was commanding.'

He was to be once again placed on the list of those killed in action at Rooyah. Once again, however, he was not to be killed, just severely wounded. He recalls:

'I could see fellows bobbing up and down, and firing from the bastion, and thought it more than probable some one would be hit. After a good deal of hard work and manual labour, we got one mortar into position, and sent one shell in all right. I was stooping down to fit a fuse for the next round, when I felt I was hit pretty hard.

The Highlanders lent a doolie, and I was supported into it, and was carried off to a tope, where the wounded were. I soon found from the great pain and loss of blood, that it was something more than a spent ball ; and then Dr. Bowhill came up, and as tenderly as he could, put me to great torture, by examining the wound. Some of the Highlanders were so jolly and kind, holding my hands and feet and forehead when the pain was greatest, and saying they'd give it the fellows for this. I staid in the tope of trees till the evening, and then the camp was pitched some distance off, and I was moved there...After one or two useless searchings for the ball with the probe, they have decided to leave it to nature, and I shall probably carry about this little memento mori in my body till the end of my days. It went in behind the left hip and has disappeared - 5 1/2 inches of probe has failed to reach it.'

His days on campaign were now done, Harington had been thrice wounded and further been struck by spent balls, taking 'bruises and scrapes' in his stride. His health was poor and the ball which had lodged in him caused constant pain and distress.

Journey's End

With his V.C. finally being promulgated on Christmas Eve 1858, Harington was permitted to journey to England, in order to see his family and undergo further treatment. It also meant he was able to receive the Victoria Cross from the hand of Queen Victoria in the Quadrangle of Buckingham Palace in June 1859. It was that Frederick Roberts (later Field Marshal, 1st Earl Roberts) was to be presented his own V.C. before Harington and family legend goes that The Queen in fact presented their awards in the wrong order, thus a swap for the correct award was agreed and completed!

Several operations finally removed the shot from his back and Harington acquainted himself with the Armstrong gun. He decided that he might proceed back to India in October 1860 and proceeded with the Sikkim Field Force in 1861. Made Captain in February 1861, he was Adjutant 6th Battalion Bengal Artillery at Agra and threw himself into the role. His letter reflects some tension however:

'My work seems to gain on me, though I have a steady average grind of 10 hours daily at my desk, sometimes more; and this exclusive of out-door duty. I've no hope of getting a holiday this year, I fear; and I shouldn't enjoy it at the expense of leaving my post-otherwise, I don't lack friends who would welcome me, and whom I would like to see.'

The book published in his memory brings this story to a poignant end:

'At 5 p.m., Friday, July 19th, he begged to be put on the sick list, and his commanding officer (Major McNeill) found him, to his horror, in the first stage of cholera. He and a brother officer, with three gunners, assisted the efforts of the doctor, and watched him with devoted attention.

His sufferings were terrible, and the exhaustion so great, that he was only able to utter a few words. To Mr. Ross, who prayed with him, and was struck by his great calmness, he whispered, "Whom the Lord loveth He chasteneth."

About 9 on the morning of Saturday, the 20th, his freed spirit joined the "blessed company" before the throne, his last faint words being "Rest, rest." Some years before he had written:

"I wonder if, when the Saturday evening of my life comes, I shall be able to watch for the morning of the eternal Sabbath, with the same calm, longing expectation which I now feel as each dear Sunday comes round!"'

Harington was buried that evening, with the 42nd Highlanders - with whom he served so bravely - providing their band and Firing Party. He was just 29 years of age.

R. Hare wrote to his family soon after his passing:

'I mourn the loss of one of my greatest friends. I knew your lamented son intimately; and a kinder friend, a more gallant soldier, I never met. He was, as you know, a true disciple of the Lord Jesus. I joined the Battery in which your son was then a subaltern, after the capture of Delhi; and on several occasions, we were detached together, with half the battery. I remember particularly at Bolundshuhur, after a shot from the enemy had disabled one of the guns of the other half battery, we were sent on in advance, under a heavy fire, and, as usual, his coolness and gallantry were conspicuous.

He was prepared to meet his God we all knew. I was also with him when he so distinguished himself and won the Victoria Cross. When he was so dangerously wounded, and hardly expected to live, all the men were constantly telling us of his gallantry under fire. The regiment has lost one of its best members.

I lived with your son at Simla for three months, when he was suffering so dreadfully from his third wound. His patience was remarked by us all ; only those that lived

with him had any idea of what he suffered.'

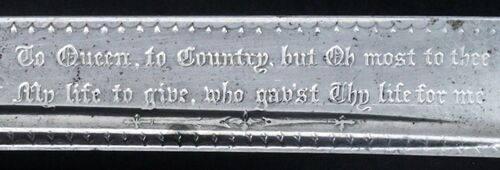

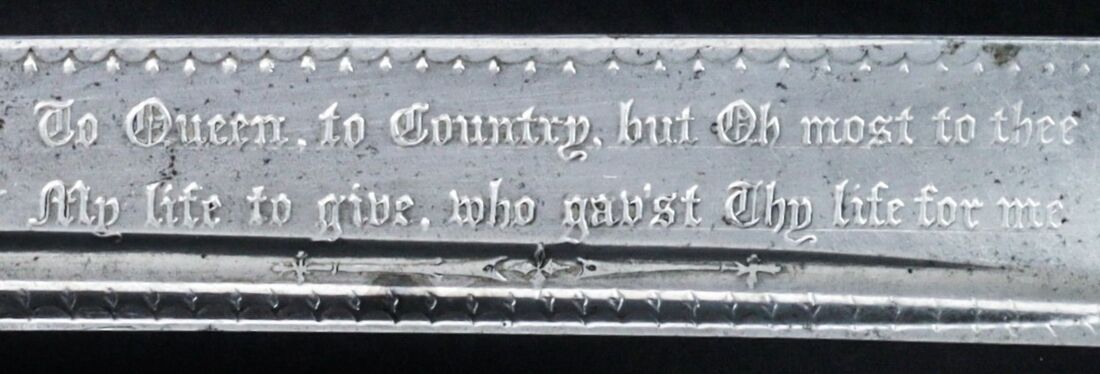

He is further commemorated upon the Royal Artillery Chapel, Woolwich, with 'Harington Road' in Formby, Lancashire and at the Royal British Legion, Endless Street, Salisbury. The final word goes to Harington and the inscription which was on his sword:

'To Queen, to Country, but oh! most to Thee,

My life to give, Who gav'st Thy life for me.'

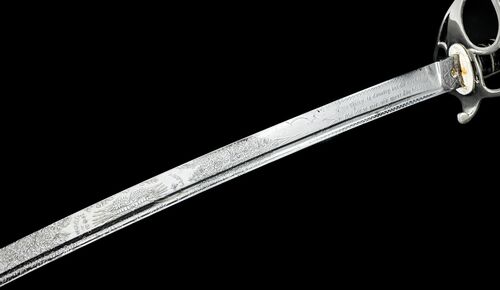

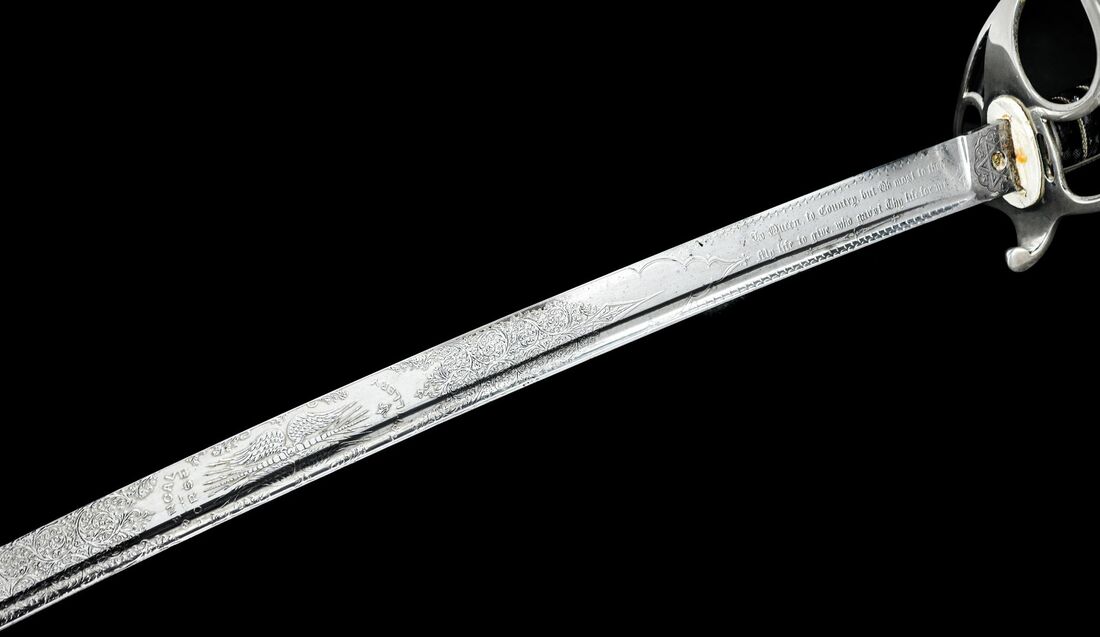

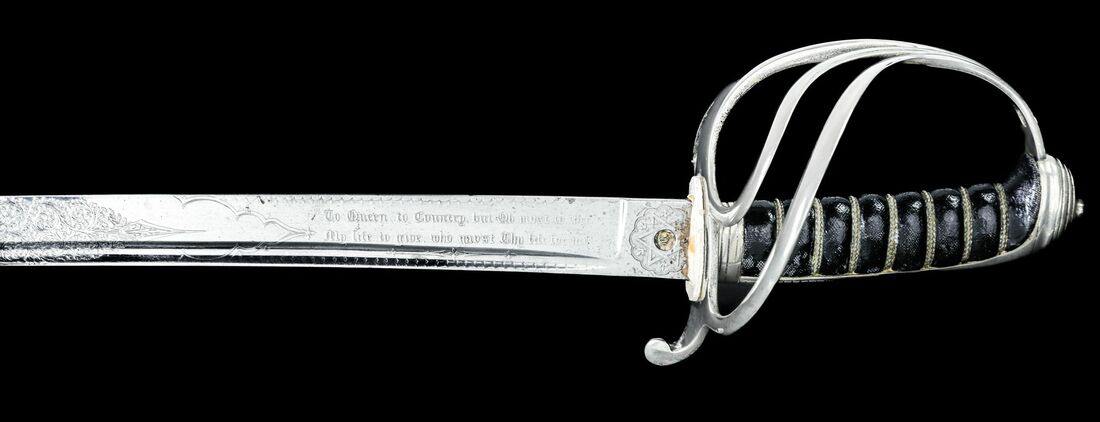

Sold together with a presentation sword, Pattern 1853 Cavalry Sword, by Henry Wilkinson, Pall Mall, London, sabre numbered '9970', one side etched with Crowns, V.R. cypher, Artillery piece, the other 'Bengal Horse Artillery', with dedication 'From F.J.O. to H.E.H.' and his motto for life:

'To Queen, to Country, but oh! most to Thee,

My life to give, Who gav'st Thy life for me.'

Reference Sources:

The Late Captain H.E. Harington, V. C., of H.M. Bengal Artillery, Nisbet & Co, London, 1862.

Eight Months' Campaign, George Bourchier, 1858.

The Indian Mutiny, Saul David, 2002.

Great Mutiny, Christopher Hibbert, 1965.

The Defence of Lucknow: T. F. Wilson's Memoir, Saul David, 2007.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£140,000

Starting price

£110000

Sale 24001 Notices

'For clarifications the correction to surname is on the Indian Mutiny Medal, the Victoria Cross naming is as issued.'