Auction: 24001 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 101

Sold by Order of a Direct Descendant

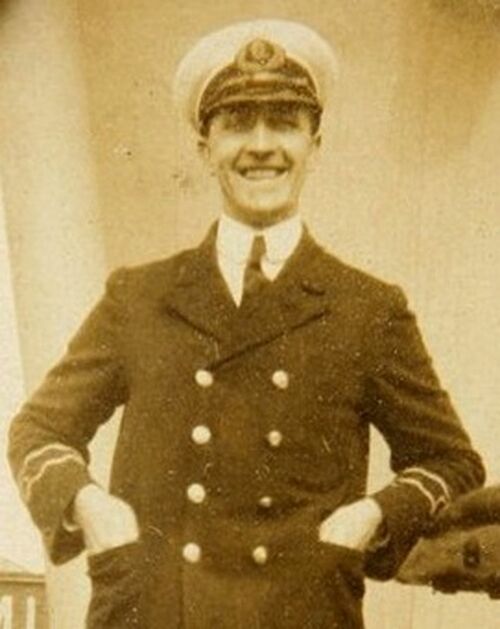

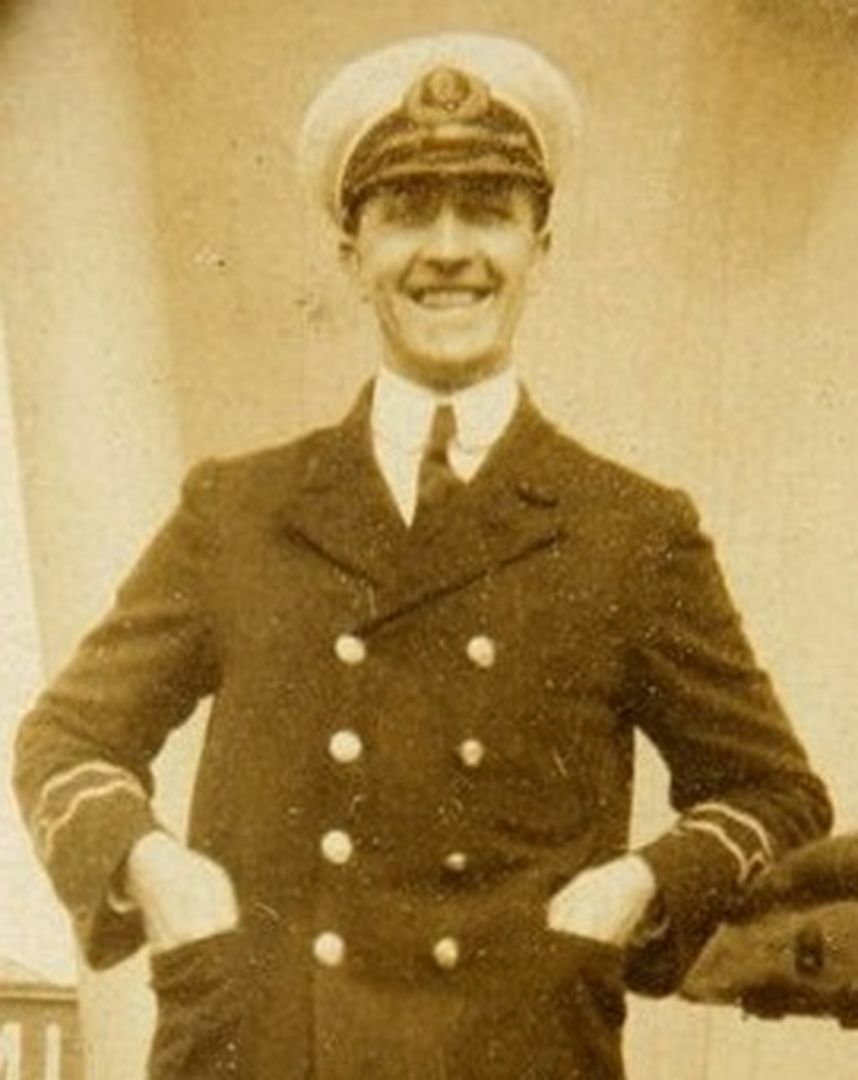

The campaign group of five awarded to Radio Officer D. Broadfoot, who earned a posthumous George Cross for his bravery during the loss of the Princess Victoria on 31 January 1953

George Cross, copy; British War and Mercantile Marine Medal War Medals (David Broadfoot); 1939-1945 Star; Atlantic Star, clasp, France and Germany; War Medal 1939-45, mounted for wear very fine (6)

G.C. London Gazette 6 October 1953:

'David Broadfoot (deceased), Radio Officer, M.V. Princess Victoria. (Stranraer.)

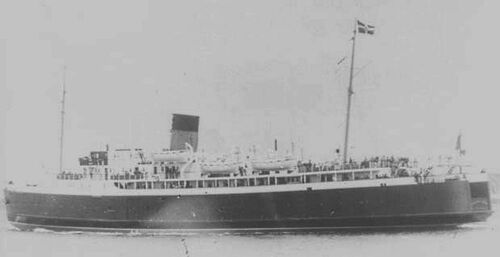

Princess Victoria left Stranraer on the morning of 31st January, 1953, carrying 127 passengers for Larne. After leaving Loch Ryan she encountered north-westerly gales and squalls of sleet and snow. A heavy sea struck the ship and burst open the stern doors and sea water flooded the space on the car deck causing a list to starboard of about 10 degrees. Attempts were made to secure the stern doors but without success. The Master tried (to turn) his ship back to Loch Ryan but the conditions were of such severity that the manoeuvre failed. Some of the ship's cargo shifted from the port to the starboard side and this increased the list as the crippled vessel endeavoured to make her way across the Irish Sea.

From the moment when Princess Victoria first got into difficulties, Radio Officer Broadfoot constantly sent out wireless messages giving the ship's position and asking for assistance. The severe list which the vessel had taken, and which was gradually increasing, rendered his task even more difficult. Despite the difficulties and danger he steadfastly continued his work at the transmitting set, repeatedly sending signals to the coast radio station to enable them to ascertain the ship's exact position.

When Princess Victoria finally stopped in sight of the Irish Coast her list had increased to 45 degrees. The vessel was practically on her beam ends and the order to abandon ship was given. Thinking only of saving the lives of passengers and crew, Radio Officer Broadfoot remained in the W/T cabin, receiving and sending messages although he must have known that if he did this he had no chance of surviving. The ship finally foundered and Radio Officer Broadfoot went down with her. He had deliberately sacrificed his own life in an attempt to save others.'

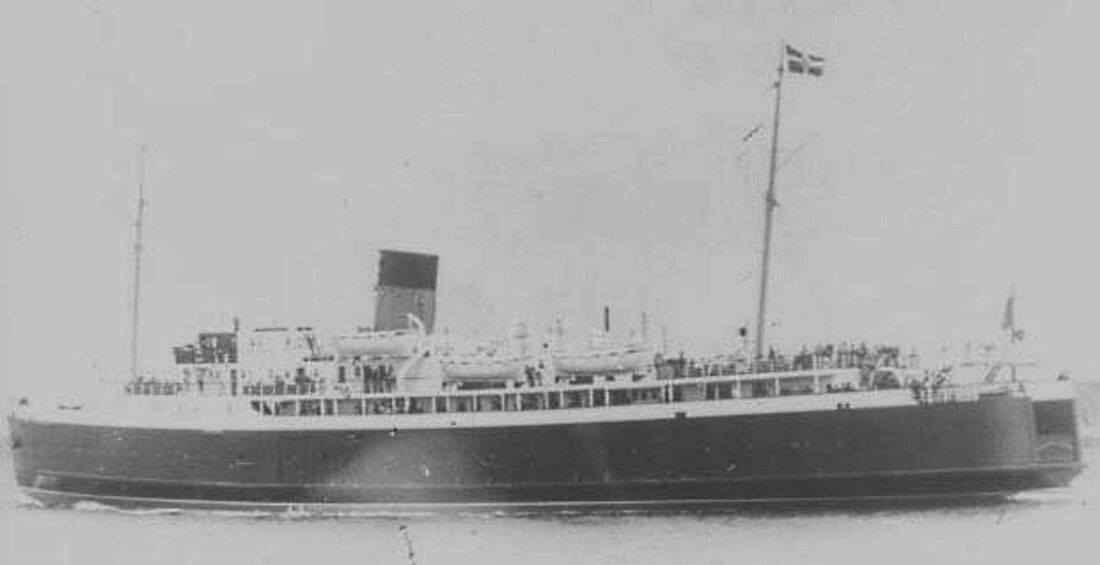

On 31 January 1953 the British Railways car ferry steamer, the Princess Victoria, left Stranraer on its regular crossing to Larne, Northern Ireland. On departure David Broadfoot who was the ship's Radio Officer, sent his routine "TR", as he had done countless times before. It was heavy weather that day, a factor not unknown in the North Channel at that time of the year, and something the ship and its crew would be quite familiar with. But disaster struck when heavy seas battered down the ship's stern doors allowing water to rush in and begin to fill the ship.

Broadfoot broadcast an XXX at 0946hrs stating Hove to off mouth Loch Ryan. Vessel not under command. Urgent assistance of tug required; this message was answered by his fellow Radio officers at the GPO Coast Radio Station Portpatrick Radio/GPK who immediately notified all emergency services.

Sadly no tugs were available and by the time the Victoria's next message was received, at 1032hrs. The situation had clearly deteriorated for this was an S.O.S., signifying the ship was in immediate danger:

Princess Victoria four miles north-west of Corsewall. Car deck flooded. Heavy list to starboard. Require immediate assistance. Ship not under command.

For four hours, in driving spray, storm force winds and heavy rain, ships alerted by broadcasts from GPK searched the position given by the Princess Victoria, unaware that she was still under way, making slow headway on one engine. For the duration of this operation Broadfoot maintained his position in his Radio Room, in constant communication with Portpatrick Radio, with immaculate WT - Morse Code - transmissions despite the horrendous weather conditions and the peril the vessel was in.

At the other end of the radio link, the Radio Officers kept a detailed log of all communications received, sent and overheard. At the conclusion of the Distress incident this log would be carefully typed out to create a certified true copy of the log which could be presented at the inquiry. Thanks to the excellent work of the Radio Officers at both ends of the communications, not to forget those on other vessels involved in the search and rescue effort, we have detailed knowledge of what was transmitted by radio during this incident.

In reponse to the impending disaster Contest set out in gale force winds from Rothesay. Attempts by Contest to obtain bearings on Broadfoot's transmissions were unsuccessful because of yawing in the sea conditions and she proceeded towards Loch Ryan on the assumption that the Princess Victoria would be in that vicinity. In fact, the vessel had been slowly drifting away from Stranraer towards Mew Island and it was not until 1335hrs that Captain Ferguson reported sighting the Irish coast.

At 1347hrs Broadfoot sent a message to say that they were off the entrance to Belfast Lough and apologised for the poor quality of his Morse code. He again apologised for his Morse code in his 1354hrs message in which he said that Princess Victoria was on her beam ends and at 1358hrs he sent a message to the Contest repeating his position. This proved to be the last message he transmitted in appalling conditions and knowing that he was trapped in the wireless office. The Princess Victoria sank off Mew Island at 1400hrs on 31 January 1953.

Ernie Jardine recalled being on duty at Portpatrick Radio when he made the exchanges with the Princess Victoria some 50 years after the event, he still could not explain why the Princess Victoria continued to give erratic positions with reference to Corsewall Point when she was almost in the Belfast Lough.

Using their direction-finding receiver, the Radio Officer's at GPK realised that their DF bearing on the ship's signals and the given position did not ally. Malin Head Radio EJM and later Seaforth Radion GLV also took bearings. While GPK's bearings were considered to be excellent, those from the other stations were considered unreliable. A reliable cross bearing was therfore not possible. Perhaps because of this, the search and rescue authorities chose to ignore the reliable DF bearing from GPK which clearly indicated that the ship's position had changed. By the time the authorities realised that the ship was on the Irish side of the North Channel and not the Scottish side, vital time had been lost resulting in disastrous consequences.

The bearing taken at 1101hrs by Portpatrick was also relayed to the Contest Lieutenant Commander Fleming of Contestappeared before Judge Campbell at the inquest into the foundering and stated that his ship could not have reached the Princess Victoria in time even if the correct position had been given. He said that during her journey from Rothesay Contest had achieved 31 knots at times, but occasionally had to slow to 16 knots. Fleming agreed with the Court that it would have been difficult for Captain Ferguson to give an accurate position with the ship listing over 45 degrees. He also stated that radio direction finding was imposible from Contest because of yawing. Jardine could not understand why the Contest had failed to get a bearing. He recalled that the line bearings taken from Portpatrick, were class A bearings (within 2 degrees), and that if a cross of any quality could have been obtained, more accurate knowledge of the distress position would have been available. A bearing from Contest would have been almost at right angles to that from Portpatrick. Yawing by Contest should not have totally eliminated the possibility of a bearing of some sort and this could have made a difference. The signals transmitted by Broadfoot tell the story of the Princess Victoria's final hour. At 1252hrs he reported that the starboard engine-room was flooded and the ship's position critical. At 1308hrs he signalled that the vessel was stopped and on her end beam end; seven minutes later he sent "We are preparing to abandon ship".

At 1335hrs Broadfoot relayed the information from the Captain that they could see the Irish coast, adding twelve minutes later that the lighthouse on the Copeland Islands was in sight. This astonished rescuers who were still under the impression that the vessel was somewhere on the Scottish side. Their search unfortunately was concentrated in the wrong place.

As Princess Victoria finally began to founder, Broadfoot maintained his transmissions and in his final communication to Ernie Jardine at portpatrick said, "sorry for the Morse - ship on beam end".

The first rescue ship to reach that spot and find survivors was the Orchy. She was one of four ships sheltering off Black Head at the mouth of Belfast Lough and joined the search after hearing GPK's DDD SOS rebroadcast Princess Victoria's message at 1335hrs stating that they could see the Irish coast. But weather conditions prevented the Orchy from carrying out any rescue itself. All it could do was tell the world the position and situation of the wreckage and the few who had survived. Captain Matheson gave his Radio Officer a message to relay: "There are a lot of people here but they cannot get hold of the line"; "Position hopeless. Cannot lower lifeboats but doing our best"..."The position is hopeless. The ship will not do anything for us". It required the arrival of smaller vessels, including the Donaghadee Lifeboat, to finally effect rescue of some survivors.

Within days of the disaster, Buckingham Palace announced that David Broadfoot was to be honoured for his bravery and devotion to duty by the award of the George Cross.

Some weeks later at a Court of Enquiry held in Belfast into the causes of the loss, Judge Campbell identified structural deficiencies which he attributed to the owners and blamed them for the ship's poor seaworthiness. Others since have questioned why the Admiralty ordered the Contest to the rescue from her base at Rothesay when there was a squadron of Royal Navy frigates and destroyers much closer in Londonderry.

Judge Campbell concluded his report by saying that if the Princess Victoria had been as staunch as the men who manned her then the disaster would have been averted. No doubt amongst the several brave seamen who exceeded their duty that day, Judge Campbell had Broadfoot in mind. He died at his post in the knowledge that what he was doing would help to save lives.

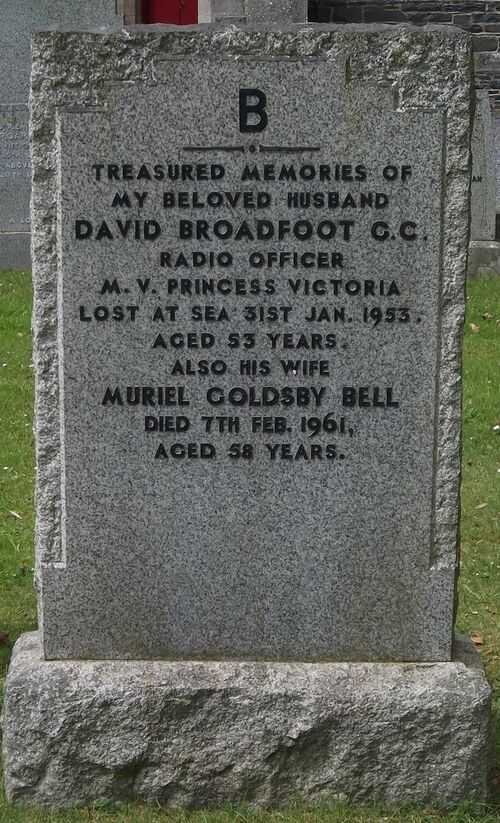

David Broadfoot was born on 21 July 1889 at Stranraer. He started his working life as a GPO messenger with the GPO Appointment Books showing that in 1917 he was already wireless qualified. He was entitled to a British War and Mercantile Marine Pair for the Great War and was the only David Broadfoot to claim Medals, with a duplicate set being sent to replace a lost set in May 1921. He held a 1st Class Wireless Telegraph Certificate (No. 4713) becoming an employee of the Marconi Wireless Telegraph company in the following decades. Broadfoot was once again was employed in the Merchant Navy in the Second World War and again was the only David Broadfoot to claim Medals. His body was recovered after the incident and he was buried in Inch Parish Churchyard, Inch.

Broadfoot's widow Muriel and his son Billy travelled from Stranraer to Buckingham Palace to receive the George Cross from the Queen.

His George Cross was donated by the family to the Stranraer Museum in the summer of 1999 and is on public display to this day, whilst his campaign group was retained by the family.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£3,500

Starting price

£3500