Auction: 24001 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 55

Sold by Order of a Direct Descendant

'On the 1st of August when the Vanguard anchor'd alongside the Spartiate, she became exposed to the raking fire of the Aquilon, the next ship in the Enemy's line, by which the Vanguard had between fifty and sixty men disabled in the space of ten minutes...Captn. Louis took his station ahead of the Vanguard; the Minotaur not only effectually relieved her from this distressing situation but overpowered her opponent. Lord Nelson felt so grateful to Captn. Louis for his conduct, on this important occasion, that about Nine o'Clock, while yet the combat was raging with the utmost fury, and he himself was suffering severely in the Cockpit from the dreadful wound in his head; he sent for his Lieut., Mr Capel, & ordered him to go on board the Minotaur, in the jolly boat, & desired Captn. Louis would come to him; for that he could not have a moment's peace, until he had thanked him for his conduct...the subsequent meeting which took place between the Admiral and Captain Louis was affecting in the extreme, the latter being over his bleeding friend in silent sermon; "Farewell my dear Louis" said the Admiral: "I shall never forget the obligation I am under to you for your Brave & generous conduct, & now whatever may become of me my mind is at peace." '

The exceptional Naval General Service Medal, Sultan's Medal for Egypt, and Davison's Nile Medal group of three awarded to Admiral Sir J. Hill, Royal Navy, who was First Lieutenant aboard H.M.S. Minotaur at the Battle of the Nile and left a rare first-hand account of the above-mentioned meeting between Admiral Nelson and Captain Thomas Louis; he later had the responsibility of commanding all the vessels detailed for transporting the British army to Belgium prior to the Battle of Waterloo, earning the Duke of Wellington's distinct praise for the efficient manner in which the movement was effected

Naval General Service 1793-1840, 2 clasps, Nile, Egypt (John Hill, Lieut.); Sultan's Medal for Egypt 1801, 48mm, gold, on its original gold chain and hook, unnamed as issued; Alexander Davison's Medal for the Nile 1798, 48mm, silver, first and third traces of old lacquer, a few minor scratches around edges, otherwise good very fine and better (3)

Of six Naval General Service medals to officers with this number and combination of clasps, this example to the most senior officer to submit a claim.

Approximately 45 2nd Class Sultan's Gold medals awarded to officers of the Royal Navy.

John Hill was born at Portsea, Hampshire, in 1774 and entered the Royal Navy (as 'Captain's Steward' aboard the bomb vessel H.M.S. Infernal) on 25 September 1781 at the tender - but not unusual - age of 7. This ship was commanded by his uncle, Commander James Alms, and undoubtedly the patronage and family interest of this future Vice-Admiral did young Hill's career a great deal of good: serving aboard Infernal until March 1783, in April 1788 he joined H.M.S. Nautilus on the Newfoundland station, before removing to various ships of the line including the 74-gun vessels H.M.S. Goliath and H.M.S. Bedford and thence on to the 24-gun frigate H.M.S. Proserpine - this latter ship commanded by that same uncle, James Alms.

Rising progressively through the positions of Midshipman and Master's Mate, Hill passed his examination for Lieutenant and was promoted to that rank on 28 July 1794, with it coming his appointments back to line-of-battle ships - specifically the Invincible, Juste, and Repulse - the latter again commanded by his uncle James. Interestingly, he appears to have been one of the officers aboard the 80-gun Juste when the Spithead mutiny broke out; fortunately bloodless (with the officers merely being turned out of their ships by the muniteers for the duration), Hill suffered no ill effects from this unusual episode in the history of the Royal Navy, and was next appointed to the 98-gun H.M.S. Princess Royal (flagship of Sir John Orde) in the Mediterranean, before transferring - as First Lieutenant - to the 74-gun H.M.S. Minotaur under the command of Captain Thomas Louis. It is worthy of note that Hill had achieved all this by the age of 24.

"Before this time tomorrow, I shall have gained a peerage or Westminster Abbey"

Fought over 1 - 3 August 1798, the Battle of the Nile was the climax of a three-month campaign across the length and breadth of the Mediterranean; a trying time for Nelson's British fleet which had inadvertantly, on several occasions, completely missed the French fleet and Egyptian invasion force. Tempers were likely frayed and officers anxious (undoubtedly Hill, as second-in-command of the Minotaur, would have felt this only too keenly) until their enemy were discovered at 2pm on 1 August moored in Aboukir Bay. Advancing during the course of the afternoon, the British ships entered the bay just after 6pm and engaged Vice-amiral Brueys's fleet directly: the two forces were almost evenly matched in numbers of ships, though Bruyes's gigantic flagship - the 120-gun Orient - tipped the weight of firepower firmly in French favour.

Minotaur was sixth in the British line of battle, immediately astern of Nelson's own H.M.S. Vanguard; those four ships immediately ahead sailed around the front of the French line, consequently engaging their enemy from an unprepared (and unexpected) direction. Bruyes's fleet was enveloped in deadly fire from all sides - but nevertheless the French fought extremely well with Vanguard herself suffering heavily from accurate cannon and musket fire from Spartiate; Captain Louis and the men of the Minotaur came to their chief's aid and Hill himself later recalled his experiences in a fascinating eye-witness account, related at the beginning of this entry. One can only imagine the scene on deck at this time, especially as darkness enveloped the participants and the flash of gunpowder lit up the night sky - even more so when the Orient exploded at 10pm. Minotaur, meanwhile, had further engaged the 74-gun Aquilon and battered her into submission - some indication of the fierceness of the duel can be seen from the casualty figures: whilst Minotaur lost 87 men killed and wounded but was overall only lightly damaged, Aquilon was completely dismasted, her captain was killed, and no less than 300 of her crew were killed or incapacitated. It is worthy of note that, in his Memorandum of Services dated 30 June 1846, Hill states that he too was 'slightly wounded, but did not return myself as such never having left my quarters', though no further detail on the nature of this wound is immediately apparent.

Promotion and further duties

As befitted the conventions of the time, all surviving senior Lieutenants were promoted Commander in the wake of this great fleet victory; Hill was additionally tasked with taking command of the captured Aquilon and sailing her (along with the remainder of the prizes and portion of the British fleet) to Malta for initial repairs and a measure of the good working relationship between Captain Louis and his second-in-command can be understood from extracts of an extant letter between the two men:

'Dear Hill,

I find it is not in the power of me to see you: God bless you & take care of Aquilon...do mind in the night & station your officers with your own Quarter Masters...you will not forget you are stronger now than you were. Let me have your news often.

Farewell in haste,

your sincere friend Thos Louis

Despite this step up in rank, Hill was destined to spend the next two years (October 1798 - February 1800) on half-pay; this came to an end on 12 February 1800 when he was given command of the troopship Heroine; not some dashing small sloop in which to make his name, but nevertheless he was lucky to have a command at last as, in 1801 - three years after the Nile - almost all the First lieutenants promoted after that battle were still unemployed on half-pay. Those officers in command of transport vessels consequently earned unenviable reputations as too lacking in patronage or ability to progress any further in their careers:

'A Transport Agent or even a Transport Commander was a desperately obscure person, outside all hope of promotion, almost outside the service. 'Some broken-winded old lieutenant, I dare say,' said Pullings, and then with a wry grin he added, 'Not but what I may be precious glad to hoist a plain blue pennant and command a transport myself, one of these days.' (The Ionian Mission, Patrick O'Brian, p164).

Hill was destined to remain involved in transport duties for the rest of his career - but despite the disparaging remarks made by Patrick O'Brian's fictional Lieutenant Thomas Pullings, he was still to see plenty of active and important service. As commander of Heroine, Hill was to spend two years in the Mediterranean conveying troops, and in this capacity he participated in the Egyptian Expedition and the landing of soldiers prior to the Battle of Abukir on 8 March 1801. This service earned him the Sultan's Gold Medal Second Class, and indeed the Log Book of the Heroine notes he also physically served ashore between 24 - 30 April.

Hill departed his first true command on 6 March 1802, thence reverting back to half-pay until 31 March 1804 when he was appointed to command the transport ship Humber; his days in warmer waters were now at an end, and until October 1808 he was exclusively stationed in and around the English Channel, before being placed on half-pay again that month.

A change in fortunes and distinguished service

It appears that some complaint against Hill had been made during his time commanding Humber as from 1808 until March 1813 he received no appointments whatsoever until a letter from one Captain James Bowen, commissioner at the Transport Board, explained the situation and altered things for the better:

'In consequence of my recommending you to be an agent for Transports afloat this Board wrote to the Admiralty yesterday for leave to employ you but upon my going to the Admiralty this day their Lordships informed me there was a note against your name very unfavourable. I told them that it was malicious brought against you by the seamen and Master of the vessel you commanded for obligating them to do their duty and that you were very hastily and in my opinion savagely treated, that you was a zealous officer, upon which I was told you should be employed…and that you may prepare to come up immediately to take charge of a Division of Transports.'

Bowen's next letter goes into more detail, and further reinforces how much patronage could count in the Royal Navy during Hill's career:

‘I have great pleasure in your getting this appointment as it will, I hope be the means of doing away with the unfortunate and undeserving charge against you at the Admiralty and as one of the Lords (I hope) is to be the commander in chief in the Baltic you may hereafter benefit by it.'

Commander Hill thus now entered into just over two years in charge of transport ships in the Baltic; by now the Allies were slowly closing in on Napoleon and his failed attempts to conquer Europe, and again his Memorandum of Services provides some fascinating additional material by noting:

'Two years and a half in the Transport Service during which time embarked and disembarked the Swedish Army from Sweden to Swedish Pomerania - received on board my ship the Crown Prince Count Bernadotte (late King of Sweden) and was honoured with his thanks for the care I had taken of his army. Sent twice to St. Petersburg to embark 5,000 Spanish Troops for which was thanked by the Spanish Ambassador.'

Recalled for duty closer to home, Hill then became responsible for transporting Lieutenant-General Sir Thomas Graham's force to Holland for the abortive attack on Bergen-op-Zoom, and also for embarking the wounded after the attack and withdrawal. A measure of Hill's good work can be observed in that Graham specifically mentions him by name in General Orders of 16 August 1814: '...the Commander of the Forces is no less indebted to Captain Hill, of the Royal Navy, for that cordial co-operation which he has on all occasions experienced from him.' He had an ally in the genial general, who had already written in June 1814 that he would 'not fail to do all I can for you at both Boards.'

By mid-1815 Commander Hill was now at Ostend as principal Transport Agent, and it was in this capacity that he acted to superintend the safe delivery of all British troops leaving the shores of England to be deposited in Flanders for the upcoming (and unexpected) Waterloo Campaign. Hill's own recollections note the following: '...disembarked the whole of the British Army and materiel prior to the Battle of Waterloo without a single accident to a soldier and the loss of only two horses. After that memorable Battle embarked all the wounded British soldiers and a large number of French wounded and prisoners.' Fascinatingly, Hill also receives a mention by name in Captain Cavalie Mercer's 'Journal of the Waterloo Campaign', arguably one of the most famous first-hand accounts of the battle and overall campaign. The situation in which Hill features is not without some wry amusement, also reflecting the difficulties surrounding the conveyance of troops and Mercer's desire to look after the men and horses of his artillery battery:

'Our keel had scarcely touched the sand 'ere we were abruptly boarded by a naval officer (Captain Hill) with a gang of sailors, who, sans ceremonie, instantly commenced hoisting our horses out, and throwing them, as well as our saddlery, etc., overboard, without ever giving time for making any disposition to receive or secure the one or the other. To my remonstrance his answer was, “I can’t help it, sir; the Duke’s orders are positive that no delay is to take place in landing the troops as they arrive, and the ships sent back again; so you must be out of her before dark.”; and I thought this a most uncomfortable arrangement.' ('Journal of the Waterloo Campaign', General A.C. Mercer, London, 1870, p. 217 refers).

Such were Hill's efforts that he came to the notice of none other than the Duke of Wellington himself, who not only gave him a well-deserved 'Mention' in his despatch (16 October 1815) but specifically recommended him to the Secretary of State for War - Lord Bathurst - for promotion to Post Captain. Bathurst responded: 'the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty in consequence of your Grace’s recommendation have promoted Captain Hill to the Rank of Post Captain.' - high praise indeed. Hill's friend, Sir Thomas Graham, was one of the first to congratulate him in a letter of 12 December 1815:

'I was extremely gratified to hear from Admiral Sir George Hope that at last your claim to promotion had been admitted at the Admiralty…Inasmuch as I consider your unremitting zeal and attention to the very arduous and often disagreeable duties of your situation most deserving of reward, I am most sincerely rejoiced to find that your claim for promotion has been admitted.’

Further honours and later life

Again due to Wellington's influence, Hill remained employed in the post-Waterloo Royal Navy (no mean feat in itself) and was next assigned to Calais where he spent three years commanding and co-ordinating the transportation of troops returning home: possibly one of his more unusual assignments was the shipment of some 7,000 Russian soldiers back to Russia - this earned him both a letter of thanks and the Order of St. Vladimir IV Class; it is believed that Hill disposed of this Russian decoration upon the outbreak of the Crimean War, hence it is not present with his British awards.

In February 1820 Captain Hill was appointed Agent Victualler at Deptford, one of the Royal Navy's three yards responsible for feeding the entire fleet; he held this post until 1838 and whilst doing so rose steadily through the positions of Comptroller (1822), Patent Commissioner (1826) and Captain-Superintendent in 1832. Interestingly, during the Irish Famine of June 1831 Hill was selected as government agent to oversee relief efforts and upon his return from Ireland in August of that year he was knighted by H.M. King William IV; as Captain Sir John he was next appointed Superintendent of Sheerness Dockyard and, in mid-1838, assumed responsibility for the disposal of the famous 'Fighting Temeraire', so memorably depicted at the same time by J.M.W. Turner.

After further periods of assistance with famine-relief in both Ireland and Scotland throughout the 1830's (earning him a pension of £150 per annum by Parliament for '...special services...superintending the relief granted in times of scarcity in Ireland and Scotland'...), Hill returned to Deptford in 1842 and eventually retired in 1851; in April the same year he was promoted, by seniority, to Rear-Admiral of the Blue and went to live at Walmer Lodge on the Kent coast - unlikely by chance to be close to Walmer Castle, the official residence of the Warden of the Cinque Ports, who was none other than the Duke of Wellington. Indeed, Wellington secured a sinecure for Hill as Captain of Sandown Castle and it must have been a great sadness to the old admiral when Wellington died in 1852; Hill is known to have participated in the vast State Funeral of November that year, in a carriage for the captains of the Cinque Port castles.

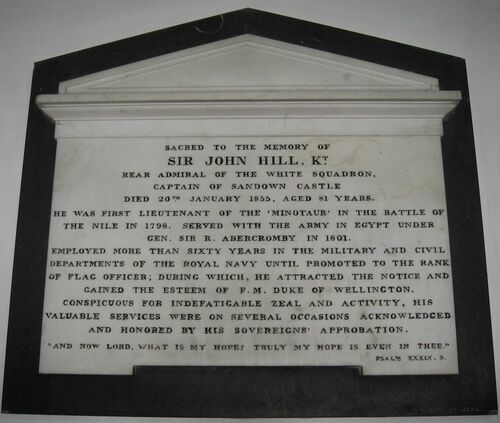

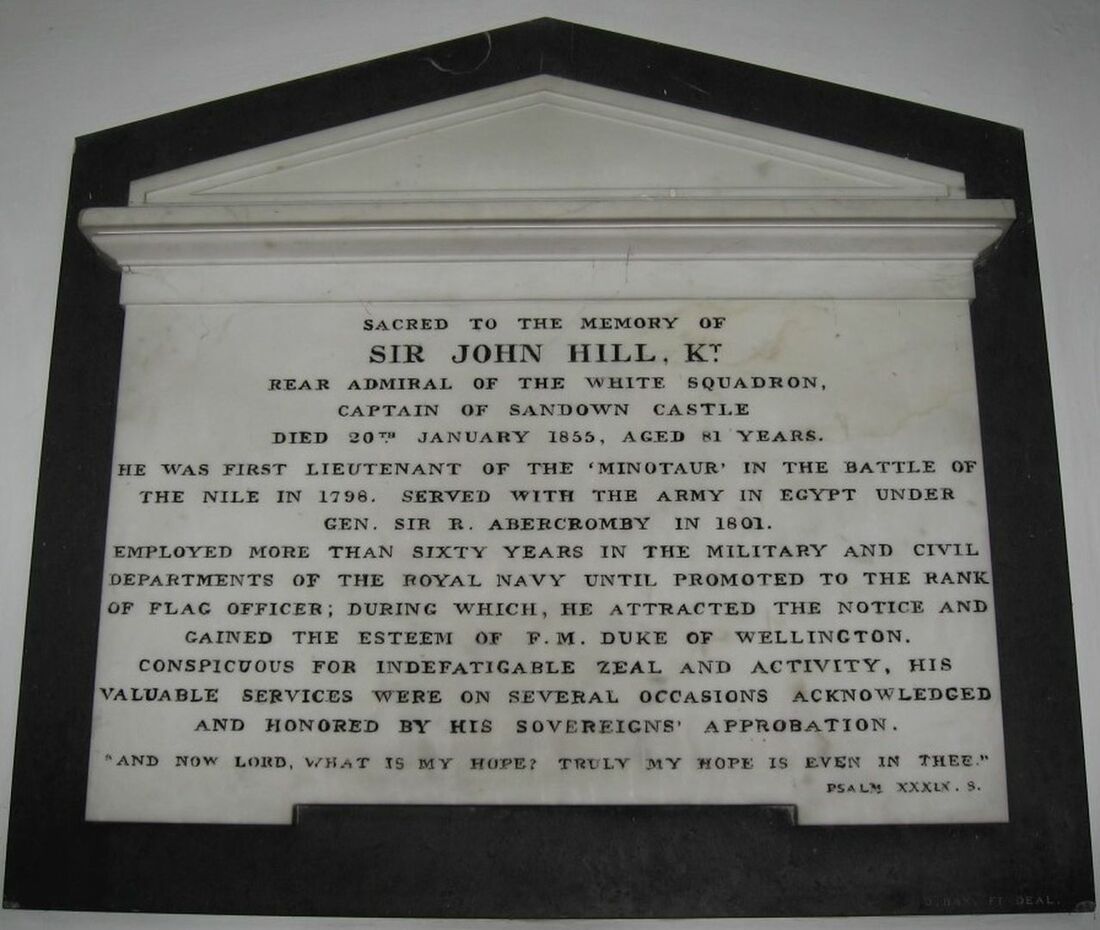

Advanced Rear-Admiral of the White in 1853, Hill himself died on 20 January 1855 at the age of 81, and is interred at St. Mary's Church, Walmer, where a fine tablet is erected in his memory. For the medals of his son, Major-General John Edwin Dickson Hill, 97th Foot, please see Lot 63.

Sincere thanks and acknowledgements are due to Dr. John MacAskill for his significant assistance, guidance and advice in preparing a number of the original documents referred to in this catalogue description.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£12,000

Starting price

£9000